by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

Stockholm is notable for many things. But we will always think of it as the city where Barbara fell in love with aquavit and discovered that the traditional cuisine of this Baltic country seemed so much like grandma’s cooking.

First, we had to get there.

We were eager to leave Copenhagen and its chilly, rainy August weather. Little did we know it had been worse where we were going, bad enough for the Norwegian Meteorological Institute to give the storm a name: “Hans.”

Hans produced gale force winds that toppled power lines and made a mess of things. A train with more than 100 passengers derailed in Sweden, injuring three people. We were ignorant of the bigger picture. Nick had received an email from SJ, the railroad company that ran the express train from Copenhagen to Stockholm, a few days before we were to leave. But the message was in Swedish and he guessed at what it said. Something about guys and directions and asking about translations. Does that sound familiar?

When we got to Copenhagen’s central station our train’s departure was absent from the message boards. Barbara charged off in search of information and Nick stayed behind to guard the luggage. She returned with urgency written on her face. “We have to hurry!” she said.

Now we knew what the message had related. The express train was cancelled. The powerful storm had affected the overhead electric lines that powered it. We’d been switched to a local to Malmo, Sweden, and would then transfer to a Stockholm train. We rushed to join the crowd squeezing onto the escalator down to the departure platform. The escalator was stuck. Barbara breezed down with her one small rolling bag.

But Nick wrestled two big black suitcases, which bulged like health warnings against obesity, or maybe overpacking, down step by tortured step. He arrived at the bottom red in the face and about to explode. His heart pounded like he would have a heart attack.

He said later he was just gasping with admiration for people who can travel with only carry-on bags.

The train pulled up, and hoisting the bags into the car was easy by comparison. We found our seats and with relief watched the passing scenery as we crossed the Oresund Bridge to Sweden. At Malmo, we changed to the second train headed to Stockholm.

We broke out sandwiches we bought in Copenhagen and settled down for the ride.

Three stops later, the train left the station, slowed, and stopped again. Time passed. Passengers started looking at their watches and then at one another, as if the person across the aisle possessed the magic answer. Finally the loudspeakers cleared their throat and an announcement came: the train crew had worked its max hours and we were waiting for a new crew to arrive.

We finally rolled into Stockholm’s central station around four o’clock and grabbed a taxi to Gamla Stan, the city’s old town and our hotel.

Gamla Stan is an island, one of fourteen on which Stockholm sprawls. We got a snapshot with our taxi’s route of U-turns and water crossings.

The Old Town or Gamla Stan was founded in the 13th century and was the the original heart of Stockholm. It’s a warren of small streets and old houses, most of which date to the 17th and 18th centuries. Its cobblestone streets and main square attract tourists from all over the world, including us.

The Lady Hamilton Hotel, recommended by our good friend Susan Raines, stood on a hill up a narrow street where private cars were banned. We unloaded over rain-slick cobblestones into a quirky place full of knick-knacks and historical tchotchkes like model ships and old wooden skis and photos of the famous and not- so-famous.

After we settled in, we wound our way through the narrow streets toward Fem Sma Hus for dinner.

We passed Storkyrkan, Stockholm’s oldest church, and the Nobel Prize Museum and came to a small square with a distinctive statue. It could be only one thing: Saint George Slaying the Dragon. We learned later it’s a bronze copy of the wooden original in Storkyrkan that dates to 1489.

It was too wet and chilly to sit outside at Fem Sma Hus, which translates as Five Small Houses.

We entered the cosy bar and chatted with the bartender, originally from Peru, as we waited for our table. He was like other service professionals, many from Pakistan, we had met in Scandinavia. They bemoaned the influx of immigrants who they said brought crime with them.

Crime is a big part of the local conversation here. Gang-related violence, primarily in Sweden’s suburbs, took the lives of 42 people in 290 shootings in 2023. Anders Thornberg, the national police chief, said, “…it was the most violence we ever had in the country.”

But in this comfortable bar, violence seemed remote. We were well into our cocktails when the maitre d’ fetched us and led us down a narrow set of stairs to the cellar where the candle-lit restaurant stretched under the vaulted ceilings of the five houses.

We had read that the restaurant offers classic Swedish cooking with a French twist and it didn’t disappoint. Barbara enjoyed a herring appetizer and we both went on to beautifully prepared filet of reindeer entrees.

The next morning we ate at the Lady Hamilton, whose cozy confines required that guests choose one of three shifts for breakfast seating. We were happy to be part of the last sitting, and then it was time to explore. The sky was clearing but it didn’t feel like August and we were glad for the warm clothes we brought. We headed off past the Royal Palace in Gamla Stan and crossed Skeppsbron or the Ship’s Bridge over Riddarfjärden Bay. Given its islands, Stockholm is also a city of bridges.

Along the waterfront we passed sightseeing boats, and a statue of King Gustav III, assassinated in 1792 in a plot of the nobility. They didn’t like his enlightenment views including banning torture and granting freedom of the press. The statue looks across the water to Sweden’s National Museum.

Once over the bridge, we walked through a lovely garden called Kungsträdgråden, or Kings Garden, that is a meeting place for many Swedes and tourists.

We were headed to the Östermalm Market Hall, which took us through a good portion of Östermalm in the eastern portion of the city. It’s one of the seven districts that make up central Stockholm.

The upscale neighborhood with a mix of townhouses and residential buildings also is home to the Royal Dramatic Theatre. A nearby street sign pays homage to the late Ingmar Bergman, one of Sweden’s great directors, and as movie lovers we couldn’t resist taking the photo.

We were on a mission and pretty much ignored the cafés, restaurants and shops that lined the pedestrian street that took us in the direction of the market.

Our destination stood out dramatically against the gray sky.

Inside we found out quickly why this is a food lover’s mecca and a bountiful market for local residents.

Cheesemongers, bakers and butchers have prominent stalls here and there seems to be something for everyone’s taste.

This wild game butcher shop caught Nick’s eye because it promised something exotic, “a taste that no domestic animal can achieve.”

Lisa Elmqvist, a fisherman’s daughter, started selling fish in the 1920s and four generations later her family company is going strong at the Food Hall with retail cases and a restaurant. Cruise their counter if you want to look a monkfish in the eye.

It was too early for lunch, but we planned to return and we asked a man stacking jars of jam about the closest museum. He recommended the Swedish History Museum a short walk away. That fit with our idea because we were deep into Vikings and interested in the way that Sweden would tell the story.

The exhibit in Denmark had taught us a lot and this equally dramatic exhibit continued the saga of the Viking era that lasted from 750 to 1100 A.D.

The exhibit took us through the social structure of Viking life that centered around the farm and family and Norse mythology that focused on nature. Those Vikings who went exploring and plundering often brought merchants and farmers with them so that they could establish roots.

This interactive exhibit offered a peek at flowers they used to dye their clothes.

We were again reminded that Vikings loved jewelry and adornment, and that these were big people. This skeleton of a six-year-old girl shows how long-limbed they were.

When we got back to the market hall the Elmqvist restaurant was crowded but we got a table. Nick ordered the house fish soup with mussels, shrimp and fish topped with tomatoes and shaved fennel. Barbara got the shrimp toast with trout roe. We both were happy.

Back in Gamla stan, we were too late to visit the Nobel Prize Museum. Our next stop was a restaurant close to the hotel called Sillkafe. Herring was a big part of the menu chalked on the blackboard covering one wall. Barbara, remembering the food served by her grandmother when she was a child and exaggerating only slightly, announced the herring was now her favorite food.

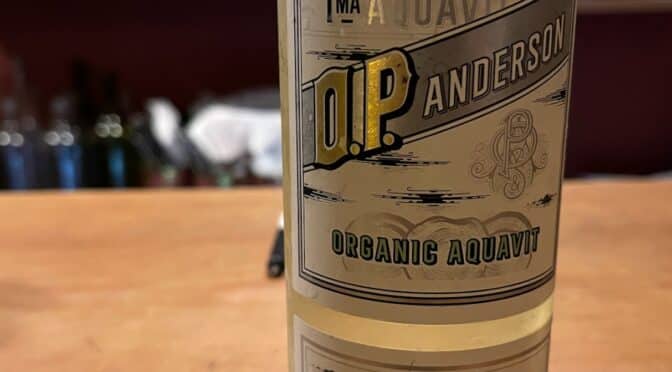

In this small restaurant our table stood near one one with a Swiss couple from Bern. They were drinking something from small tulip glasses. Our enthusiastic waiter Marena insisted we try it, and explained the mysteries of aquavit. It’s an 80-proof clear spirit like gin or vodka, flavored with aromatics like caraway, dill, anis or fennel. Scandinavians started hoisting glasses of the stuff in the 15th century and it’s become a national spirit in the region. Naturally, we had to try it.

The next morning we had some time before the overnight ferry we would take across the Baltic to the Gulf of Finland and Helsinki. That meant a visit to the Nobel Prize Museum, which was right around the corner.

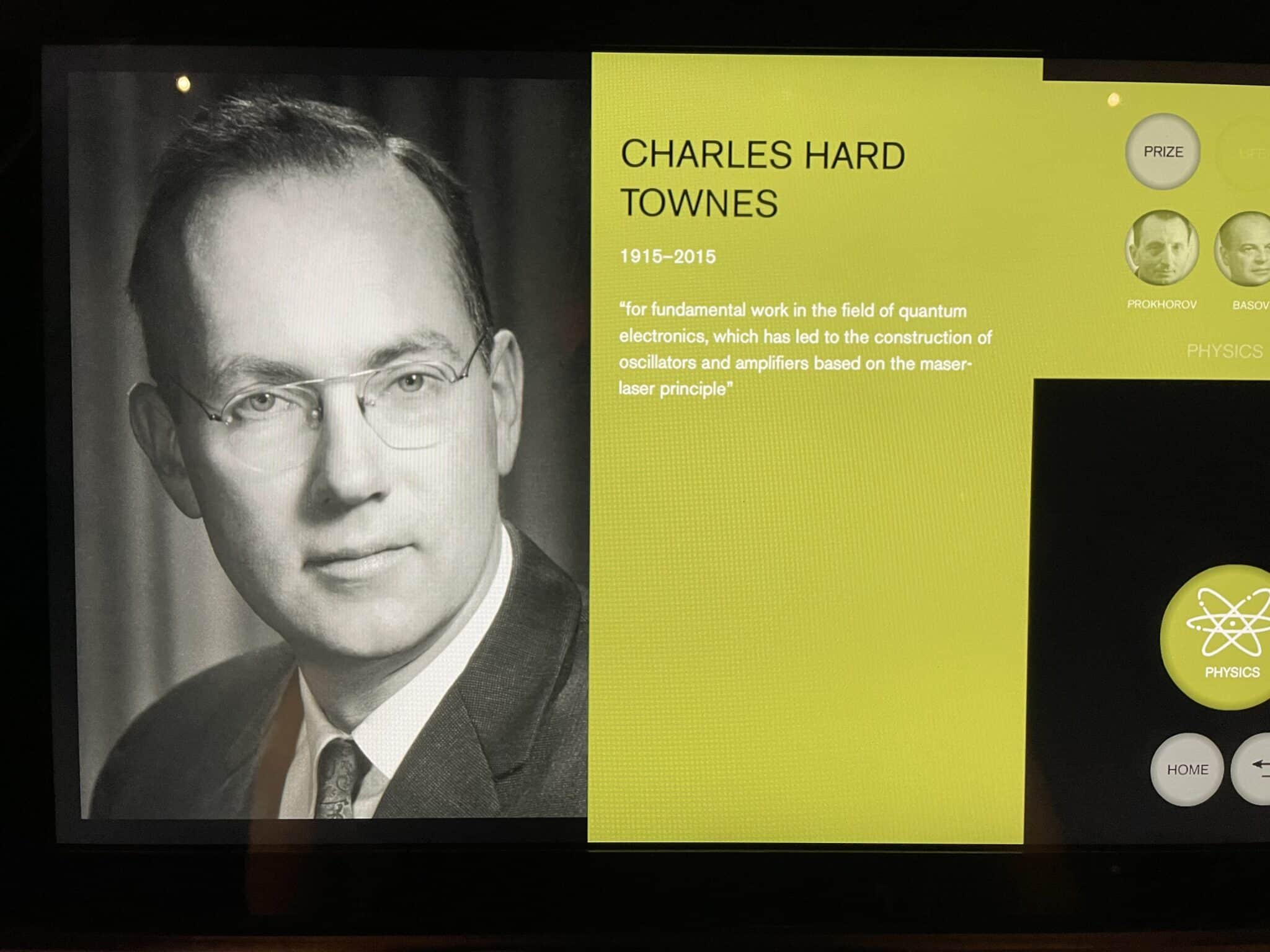

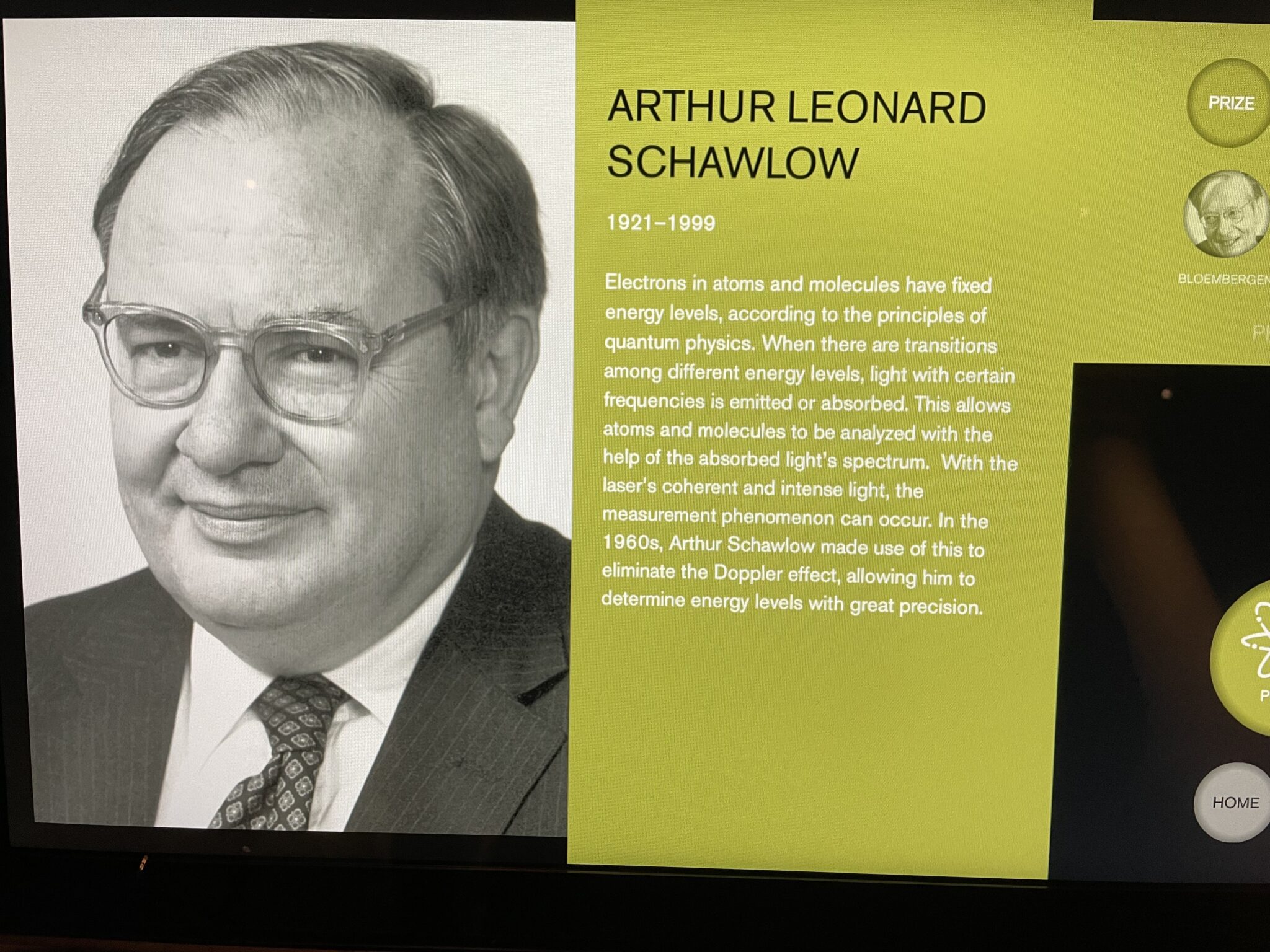

Nick had met and interviewed two physics Nobelists when he was writing LASER: The Inventor, the Nobel Laureate, and the Thirty-Year Patent War. So we checked out the displays of Charles Townes, one of three 1964 physics winner, and his brother-in-law Arthur Schawlow, one of three winners in 1981.

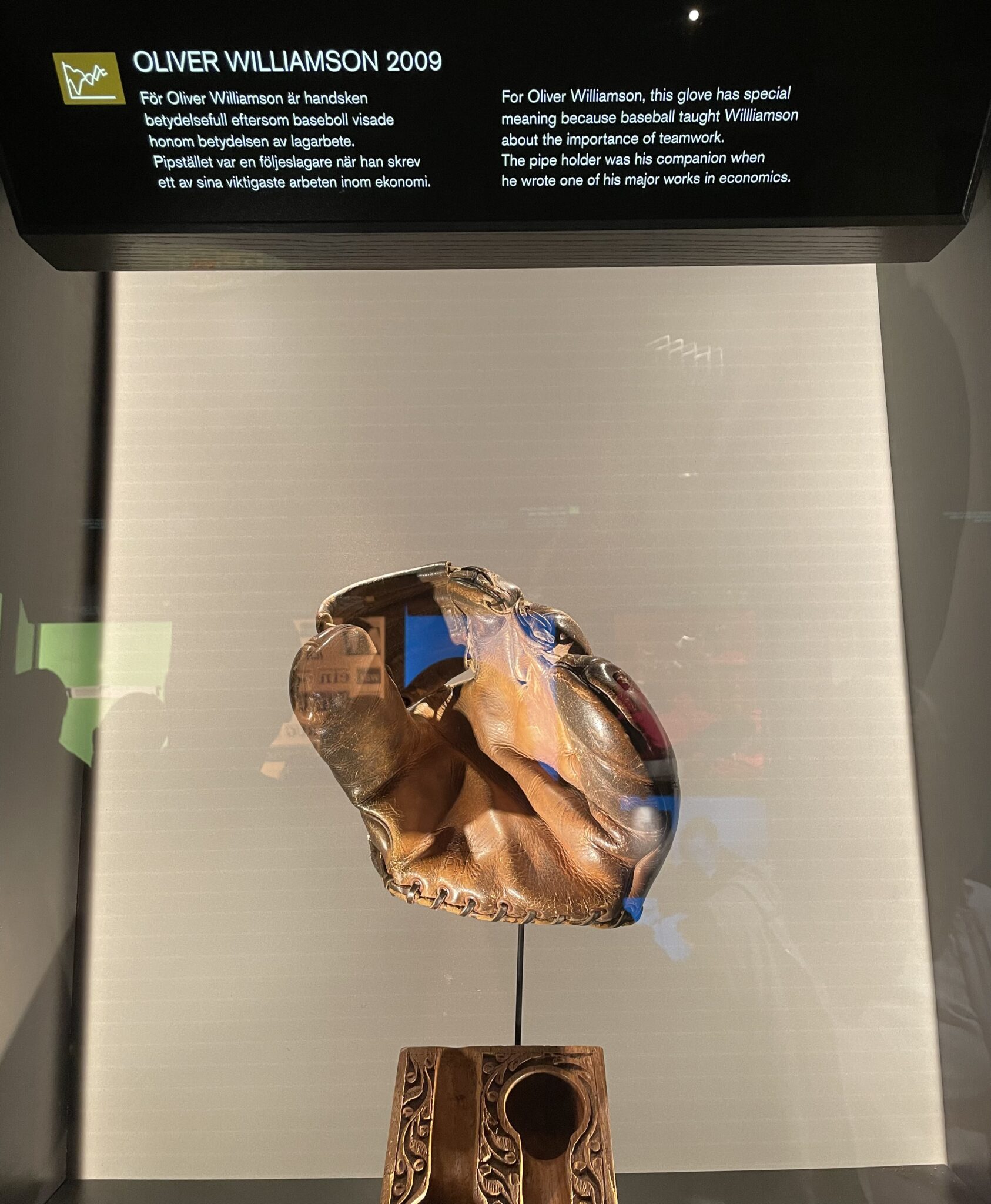

Many of the Nobelists in all fields donated something personal, and Nick liked the object from Oliver Williamson, who won the 2009 Nobel in Economics. Williamson sent the museum his baseball glove, and said it demonstrated the value of teamwork.

After we left the Nobel Museum, we noticed on the side of same square another museum in a different field.

The Wooden Horse Museum was really a store that sold trinkets. But a wall display did have printed instructions on how to make a wooden horse. And we learned that Swedish hand-carved folk art horses were so popular at the New York 1939 World’s Fair that over a ton of them were shipped from Sweden to the United States that year.

Before going to check out of the Lady Hamilton, we detoured into the courtyard of the Royal Palace to watch the changing of the guard. The guardsmen are members of the Swedish military and perform this ritual every day from April 23 to the end of August from about 12:15 to 1:15.

The guard changed, we returned to the hotel and packed. A taxi took us off of Gamla Stan and east to the Tallink Silja ferry terminal, where we boarded for our overnight voyage to Helsinki.

No ABBA Museum?

Ha! Not for us, this time.