Sarajevo and Mostar

by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

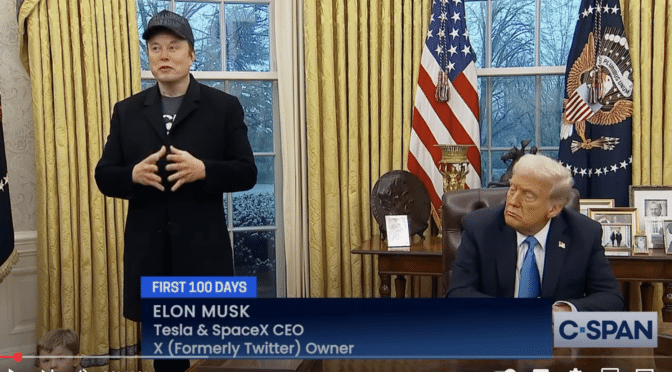

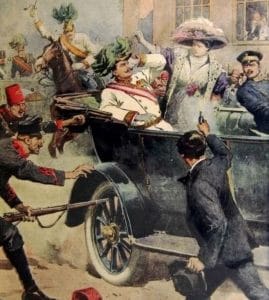

The road into Sarajevo follows the Miljacka River. We turned off at the Latin Bridge, where in 1914 Gavrilo Princip, a nineteen-year-old Serb nationalist, squeezed off the shots that killed the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and started World War I.

The city’s old quarter was just a block away and to our delight we saw signs reserving parking spots for the Old Town Hotel, which we found via Booking.com. We checked in to a small but spotless room that faced the back of the Gazi Husrev-bey mosque

and went out to take a look around. True to its name, the Old Town Hotel hugged the edge of the old quarter’s pedestrian zone, crowded on a summer Saturday evening.

For centuries Muslims, Catholics, Jews, and Eastern Orthodox Christians made Sarajevo a thriving cultural and trading center.

Some may remember the beauty of images of this city, tucked in a valley surrounded by mountains, from the 1984 Olympics.

But gold and silver in the hills of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Bosnia) put the area on the Romans’ trading map. By the 12th century Bosnia had become an important stop on the trade route between Constantinople and the City-State of Ragusa, the town now known as Dubrovnic.

When the Ottoman conquerers took hold in the 15th century, they built up Sarajevo and Mostar with roads and bridges and the prosperity that followed led many of the South Slavic Christians to convert to Islam.

Jews had long moved through the city as traders. But, in 1541, they came to settle from Salonika, where their families fled from Spain during the Inquisition. In the 17th century, Ashkenazi Jews fleeing persecution in other parts of Europe, also made their homes in Sarajevo.

The history of its rich religious and cultural mix attracted us to Sarajevo. All its elements seemed represented in the crush of people in the Old Town’s central square, which felt more like Istanbul than Istanbul.

Tourists from the Middle East, men in dark slacks and colored shirts with fat flashy watches on their wrists, women in black hijabs hiding everything but their eyes, mingled with visitors from Asia, Europe and elsewhere, many dressed in tiny skirts, ripped jeans, halter tops, or rompers.

Restaurants, cafes, and shops selling everything from antiques to underwear lined the narrow streets leading to the square.

You could buy pens and flashlights made from rifle shells if you wanted a souvenir of the 1990s war.

Barbara found a contemporary jewelry shop, with work by the Bosnian sculpture Ibrahim Handzic, and bought a pair of pretty earrings.

Croatia’s kuna was behind us now and we needed Bosnian money, convertible marks worth about sixty cents each. In the mix of people and stuff, we found a cash machine.

To catch our breath and get away from the intensity of the tourist zone we took refuge just outside the Old Town, at the Hotel Europe’s spacious garden café overlooking the ruins of the Taslihan, a stone inn built in the 16th century.

The Hotel Europe has plenty of stories of its own.

The Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was headed to the Hotel Europe with his wife Sophie when Princip shot him.

But on this evening, the crowd laughing and talking over coffee, tea or cocktails didn’t seem interested in Sarajevo’s bloody history. We, too, had other things on our minds: food and a taste of Bosnian wine.

The concierge at our hotel had recommended three restaurants, and we looked them up on a blog Barbara found called CultureTrip that offered good restaurant tips.

We chose Dzenita on a side street that goes up the hill in Old Town. We sat side by side at a picnic-style table in front of the small restaurant and ordered delicious stuffed cabbage

and smoked meats appetizers and veal skewers and grilled sweetbreads mains.

We barely began to eat when we struck up a conversation with an Australian couple. They had been in Sarajevo for two weeks, a blip in their two-year road trip around the world.

“We rented out our house to lovely people and now we rent wherever we go. We have a nice apartment just outside of Old Town,” Alice said.

We asked what they had done for a living. “I’m a nurse,” John, the husband, said. “And I worked in finance for a bank,” Alice explained as she looked over their check.

They had just come from the Adriatic coast of Croatia and the island of Brac, where we planned to go. “We loved it. We found beautiful little coves just outside of the town of Sutivan where we stayed,” John said.

“Sutivan!” Barbara nearly jumped from her seat. “That’s where we’re headed eventually.”

We swapped stories and went back to our plates when they left.

A young Japanese woman sat down by herself and ordered a salad. She caught our eyes, and said, “I’m so tired of meat. I have to have something else.”

She had come to Sarajevo after a stay in Ireland where she studied English. She asked if she could join us at our table.

Her name was Asahi – “like the beer,” she said – Takashi, twenty-one, beautiful and bubbly.

“Why did you come to Sarajevo?”Barbara asked. “I am studying human rights,” she said.

And we understood. Our interest in human rights — and what can happen when they’re thrown out the window — also brought us to Sarajevo. Like us, Asahi also had romance in mind and she laughed as she explained that she planned to go from here to Barcelona to visit a boy she met.”

“Barcelona. A sexy city,” Barbara said. Both women laughed knowingly.

Asahi described a tour she had taken that day to some of the hard to-get-to spots and recommended we take one. We exchanged Facebook information and said goodnight.

When we got back to the Old Town Hotel we chatted with the night manager, who told us he was a musician. “The music fills my soul. I must do this hotel job for a just little while longer, I hope.” Barbara punched up YouTube and the Epichorus,

a group affiliated with the New Shul in New York City that plays ancient Arabic and Jewish music. He watched, listened and swayed as he closed his eyes. “It’s my rabbi’s group,” Barbara told him. He smiled and said, “It gives me the chills.”

No one who wasn’t there can fully understand how multi-ethnic Sarajevo suffered during the 1990s war. Muslims made up 45 percent of the population of Bosnia, Eastern Orthodox Serbs 36 percent, Catholics 15 percent, Jews 3 percent and Protestants 1 percent. And before the war 30 percent of the marriages in Sarajevo were mixed.

But the war set Serbian militias with Croatian Catholics against the entire population of Sarajevo, turning what had been called the Jerusalem of the Balkans into a living hell.

In the photo below, a Serbian commander, as a joke, holds a toy pistol to the head of his son. Sarajevo officials suggest snipers killed 600 of the city’s children.

The Serbs rained mortar and tank shells on the city and, with the snipers, killed almost 14,000 people including more than 5,000 civilians.

Steven Galloway’s wonderful, painful novel, “The Cellist of Sarajevo,” based on a real character, suggests what it was like.

But we wanted, as best we could, to gain a closer view.

We decided to heed Asahi’s advice about the tour and the day man on the hotel desk suggested Spirit Tours. We signed up for a trip to the surrounding hills.

A group of us, people from Italy, Australia, England, Spain, and a couple from Sweden and Istanbul who now lived in Dubai, met in a small office and headed to the tour van with our guide Enes Popara. We jumped at the chance to ride in a separate car with Enes and a driver.

Enes communicated with the van through his cell phone, which they heard on speaker.

We asked about the real life cellist of Sarajevo, “He played in there,” he waved his hand pointing to an area near a pedestrian mall.

And then almost immediately, we drove out into the new portion of the city and he said, “This is sniper alley.”

He pointed to the hills on the other side of the river, and the modernish high-rise buildings still pockmarked and scarred by constant bombardment.

“This is the Holiday Inn where all the journalists stayed and it was regularly shelled too. They targeted everything here,” he said.

Our route led west out of the city. One building, about six stories high, stood gutted and empty as a haunting reminder.

Enes told us his family lived in a street above the Catholic Cathedral. “We have a government now that represents three sides,” he said. “But it’s crazy, we are one people. Just look around, everyone looks the same. We are all originally South Slavs. You can’t tell who anyone is unless you ask their last name.”

And we realized that he was right. With the exception of the observant women from the Middle East draped in black, the locals, even the women with headscarfs, all looked similar.

Turning south and crossing the Miljacka River, we climbed past Sarajevo’s airport, turned left and stopped outside a rustic building marked Tunel Spasa.

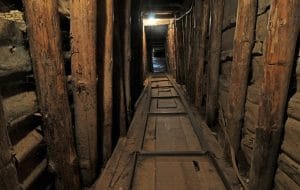

The Tunnel of Hope was Sarajevo’s supply line from the outside world during the Serbian siege. With water, food and other necessities cut off, Bosnian army workers dug around the clock for four months to build the tunnel during the spring of 1993.

The tunnel stretched under the airport for more than half a mile, angled midway to keep Serb gunners from guessing its path.

It was tiny, barely three feet wide and less than five feet high. But 20 million tons of food traveled through it into the city, as well as water, fuel and weapons, and a million people traveled in and out.

Enes described all this with passion and some anger. He was a child during the siege.

“We had no food. We ate potato scraps, garbage, anything we could find,” he said. “We got packages with food, marked Vietnam. They were left over from the Vietnam War and that’s what we ate,” he said. “We had no water and had to get water where we could.”

“It gets cold in Sarajevo and we had no heat. We scavenged for anything to burn and many burned car tires in their homes.

His father suffered frostbite fighting in the hills, but the real problems didn’t kick in until years later. Enes said that since 2012 his father has struggled with serious post-traumatic stress disorder.

He led us into the basement of the house where, stooping and covering our heads, we shuffled through a few feet of the claustrophobic tunnel and saw firsthand just how precarious Sarajevo’s lifeline was.

From the tunnel museum we piled back into the vehicles for a trip to the hills on the other side of the city.

But on the way, as the driver tried to take a shortcut to the road north, a group of people walking to a funeral refused to budge from the road.

We realized we had crossed into a section of the Republika Srpska that hugs Sarajevo, and the Serbs on this road were claiming their territory against all comers. We took another road. And when the van failed to show up in our wake it turned out that a Republika Srpska cop had stopped it for no good reason. Enes, and later the van driver, said that the cop wanted money.

When we reached the city’s northern hills we took pictures from an overlook. The beautiful view led us to pose for photos, but you also realized just how vulnerable Sarajevo was to shelling from those hills.

Then we climbed some more, to the abandoned concrete luge-bobsled run from the 1984 winter Olympics held in Sarajevo.

The half-tube swept dramatically downhill, pitching left and right, its high-sided curves tableaus for

The half-tube swept dramatically downhill, pitching left and right, its high-sided curves tableaus for

colorful graffiti. We followed it on foot.

Near the bottom Enes pointed out another reminder of the 1990s war. Where the sled run branched off and leveled to a slowing point, a hole punched in its concrete side marked the nest where a sniper had fired at Bosnian soldiers advancing through the surrounding forest.

And then he showed another sniper shooting hole in a pipe toward the end of the run.

The personal background that Enes brought to the tour made him a brilliant and compelling guide. And you didn’t have to go far in Sarajevo to find others whom the war had touched, and changed.

After the contrasts of the luge track, we piled back into the car and van and headed to the Jewish cemetery on lower hill overlooking the city.

“This is one of the oldest and largest Jewish cemeteries in Europe,” he said. But he really brought us here to show us where snipers hid as they fired into the city. “You can see on the tombstones, some knocked down, some with chips from bullets, the evidence of war,” he said.

Back in the city, we said goodbye to Enes, who hopes to run for office or work in the Ministry of Tourism to help Sarajevo and bring people together.

The outdoor cafe at the Hotel Europe called to us again. The tables were almost empty on a Sunday afternoon, and the waiter had time to talk as he delivered our prosecco.

After we told him we had taken the tour, he said, “My father was killed in the hills. I was one and my brother was five. My mother had two boys to raise and I don’t think she was ever the same.” He had studied to be a physical therapist and was getting his final certifications. He’d been offered a job in Berlin “but I don’t know,” he said. “I worry that I shouldn’t leave my mother.”

We needed comfort that night, and we found it at 4 Some Gospode Safije, the Four Rooms of Mrs. Sofia, a ten-minute taxi ride from our hotel.

The restaurant wrapped us in warm wood and stone with chandeliers hanging from the beamed ceiling overhead. The traditional Bosnian menu emphasized beef and slow-cooked lamb with modern touches and a range of fish as well. Bosnia, like the rest of the Balkans, produces excellent wines and we tipped out hats to the house white.

While we waited for the taxi that would take us back to the old quarter, our waiter showed us Mrs. Sofia’s other three rooms — a wine and tapas bar, a lounge, and outdoor seating in a garden.

In the morning we wanted to see the famous Sarajevo Haggadah. The 14th century illuminated manuscript for the Jewish Passover service was saved from the Nazis by the Muslim chief librarian of the Sarajevo National Museum. He brought it to a Muslim cleric in Zenica, north of Sarajevo, who legend has it hid it either beneath the floorboards of a mosque or in a Muslim home.

During the 1990’s war it was locked away in an underground bank vault. After the war, the Haggadah was restored and put back on display at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. We missed it though because the museum is closed on Mondays.

So we went to Sarajevo’s Jewish Museum instead.

We took a short walk from our hotel, and found it practically next door to the Gazi Husrev-bey mosque. The 16th century synagogue that now houses the museum speaks to the centuries-old diversity that the Serbian siege attempted to destroy.

The thick stone walls and the beautiful restoration created a cool serenity, a far cry from the blistering heat outside. The exhibits chronicled the arrival of the first Jewish settlers in Sarajevo and the city’s prominent Jewish families. Many of them fought as anti-fascist partisans during World War II. The exhibits also told the story of the atrocities against the Jews, and it highlighted the the work of local Jewish artists.

The Book of the Dead hung from the ceiling, fastened at a corner so that it hung at an eye-catching angle. The dead, in this case, were the 12,000 Bosnian Jewish victims of the Holocaust. We found it a sad irony that the 1990s war diminished Sarajevo’s Jewish population even more. Fourteen thousand Jews lived there before the war and the siege. There are said to be just 1,000 now.

Sarajevo’s synagogue, the only one still functioning, lies across the Miljacka River from the old town.

We stopped in and Barbara talked with Dr. Eli Tauber. Married to a Muslim woman, Tauber is a journalist, historian and board member of Humanity in Action, a local NGO. During the 1990’s, like many other Jewish Sarajevans, he fled to Israel. Barbara wondered how his family survived the holocaust.

“Many of the Jews from Sarajevo went to Mostar. They were protected there by the Italians and then in 1943 (when the Italians surrendered) they became partisans,” he said.

German troops had captured Sarajevo in 1941 and immediately destroyed the synagogue. The Croatian Ustase, acting as rulers for the Nazis, rounded up Jews and deported them to Auschwitz or concentration camps in Croatia. They killed 85 percent of the Jews from Sarajevo.

An estimated 1500 Jews escaped to Mostar, controlled by Mussolini and Italian facists. Athough Mussolini was no friend of Jews, the Italians protected them from the Ustase and moved some from Mostar to camps on islands on the Croatian coast.

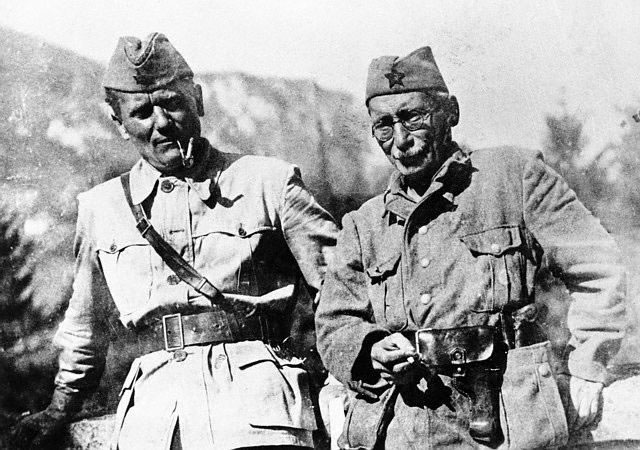

Like Tauber’s parents, many about 4500 Jews became partisans fighting with Tito. We found a photo of Tito and Mosa Pijade, who became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

Walking back across the river, Barbara and a Muslim woman shouted a warning to a pedestrian who stepped into the street as a car was bearing down. In Barbara’s world that starts a conversation.

The woman, twirling a tail of her beige headscarf around a finger, asked in halting English where she was from. Barbara told her and the woman asked, “Do you like Sarajevo?” “Very much,” said Barbara. “But it breaks my heart.”

“Go to Srebrenica,” said the woman, named Danele. “Your heart will break even more.” In 1995 Serbs killed more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys and hid and buried many in mass graves.

As we loaded up the car and hit the road for Mostar, Barbara said, “I think every Jew in the world has a responsibility to help the Muslims of Bosnia. We should understand this kind of persecution.”

Later we learned that Eli Tauber, the man she met in the synagogue, was also the author of When the Neighbors Were Real Human Beings. His LinkedIn profile describes it as stories about “righteous people from Bosnia-Herzegovina.” He also leads the Institute for Researching Crimes Against Humanity at the University of Sarajevo.

We had a lot to think and talk about and wondered what Mostar would bring. The beautiful drive took us west and south through the Dinaric Alps and then followed the south shore of Lake Jablanica, an artificial lake formed by damming the Neretva River.

The waters reflected the clear sky overhead; there hadn’t been a hint of rain since we reached the Balkans. At Ostrozak, a bridge crossed the lake’s blue expanse and we stopped to take a picture.

The dirt pullout where we stopped was attached to a house just off the road. As we aimed our phones, a man appeared at its door and gave a beckoning wave. “He’s inviting us in,” I told Barbara.

We walked down and the man indicated that we should leave our shoes next to his outside the door. We did and he led us inside, past the bed where he slept to a narrow terrace that overlooked the lake. Here he pulled out strips of cardboard for us to stand on.

I patted my chest and said, “My name is Nick. And this is Barbara.” He told us that his name was Jacobo. After handshakes all around, we took our pictures, retreated through the tiny house, and left in the glow of Jacobo’s unexpected hospitality.

The lake narrowed and the road now followed the Neretva River.

Signs at the town of Jablanica announced the Restoran Zdrava Voda — it means “healthy waters” — somewhere up ahead and when we reached it we pulled into the crowded parking lot.

Enes, our tour guide in Sarajevo, told us to stop at one of the roadside restaurants and order “sheep.” This restaurant had a terrific view of the river and we waited to sit an outdoor table. Looking around, we saw that almost everyone had done as Enes suggested; forget the heat wave, this was a place people came to for its roasted lamb.

It came succulent and falling off the bone with tasty lightly browned potatoes.

We saw the secret as we left: three large water-driven wooden wheels slowly turned spits of lamb above wood fires, the long cooking process a foodie’s dream.

If the meal had made us sleepy, the road to Mostar woke us up.

It weaved from one side of the river to the other against stark cliffs, through tunnels and cuts blasted through the rock, every turn upping the ante to show us a more dramatic landscape than the one behind.

The ethnic and religious divide differs from that of Sarajevo. Serbians have found themselves victimized here. During World War II, Mostar was run by the Croatia’s Nazi puppets, the Ustase. They arrested Serbs en masse in 1941, slaughtering everyone they could.

And in 1992, it was Croats who attacked and shelled Mostar from the surrounding hills.

On our drive into the city we discovered that Mostar clusters on both sides of the Neretva River, like Sarajevo on the Miljacka.

Nick stopped to ask a woman if she could point us toward our hotel and she said, “It’s best if you follow me. I live in the same neighborhood.” We followed her for several blocks until she pointed at a street to turn on, and a few doors on was the Sinan Han Motel.

A smiling young woman named Yasmina greeted us and offered cold drinks of water with mint, or lemon. The place was was small but charming, with no elevator and a tiny room that we almost overflowed. Outside our room were steps to a rooftop terrace with a view of the Stari Most, the Old Bridge that is Mostar’s most famous monument, about 100 yards away.

We met Marijana, the attractive owner, on our way out to take a closer look at the bridge. She told us the Sinan Han was still being built atop the foundations of an old home when the Balkans war stopped construction. Refugees made homeless by the war lived in its cellar and Bosnian troops occupied the rooms upstairs.

On our walkabout,

we reached the bridge through a warren of narrow stone alleys lined with shops, the stones underfoot polished by centuries of footsteps.

The Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent

ordered the bridge built and workers finished it in 1566. At the time its arch of about ninety feet was the widest in the world. It survived for 427 years until Croatian shelling collapsed it in November 1993.

After the war’s end, restorers used original techniques and materials and some of the original stones salvaged from the river below to rebuild it. It reopened in 2004 and is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Tourists teemed on the bridge’s peak. We climbed its sharp rise to the top, where divers had plunged into the river to earn tips. Now diving is restricted to a competition every year. The stones underfoot, which seemed to be salvaged from the originals, were slippery with wear.

That evening we researched restaurants through CultureTrip, and longing for simple grilled fish came up with Restoran Harmonija a little way upriver from the bridge. The restaurant’s website points out that it faces the mosque and the Serbian orthodox Christian church, highlighting how people lived together peacefully until they didn’t.

We sat in the moonlight at the edge of a terrace, with a view of the river giving us the most romantic setting of our trip so far.

Although it is a Muslim-owned restaurant we checked beforehand and they did serve alcohol. The charming waiter greeted us with two small shot glasses. Nick got a firey man’s drink and Barbara a sweet, potent glass of fruit brandy.

We ate local trout, a relief from the meat-rich meals we’d had so far, washing it down with the house-made white wine.

After breakfast at the Sinan Han, we crossed a bridge downriver and saw that the city still bears the physical scars of the war.

We spent some time at the Mostar Museum, then returned to the Stari Most and its surrounding shops where Barbara had her eye on a blouse and some table runners.

Barbara bought the runners, made in Kosovo, from Amira, a beautiful young woman wearing a modest head scarf. They began to talk and Amira said, “This is a very sad day for us. You can hear the stores are not playing any music. It is the anniversary of the massacre at Srebrenica.” Tears filled her large brown eyes. “You know about the massacre?” she asked, and Barbara nodded. “I never know how people can be so cruel. We are all people,” Amira said.

Barbara asked her if she remembered. “I was very little and they sent me to the hills,” she said. “But I remember how scary it was. We had nothing here. We had no army. They took all the guns and uniforms from the capital in Belgrade and we . . .” she paused and ran her hands down her clothes “. . . had nothing.”

Mostar’s political scars still run deep. The city hasn’t had elections since 2008 because of divisions between Croats, Muslims and Serbs.

As we walked back to the Sinan Han, we wondered anew how in the 1990s, what happened in the Balkans could have seemed so far away and left us, relatively speaking, so unmoved. We are after all, as Amira said, all people.

Perhaps the region’s troubled history gave the people we met here a sixth sense. They were very interested in politics in the United States and confused and appalled by Donald Trump’s first months as President.

As we checked out, Marijana’s teenage son Arnel and the receptionist Yasmina asked us about him. “How can Americans make him president?” they wondered. We talked about the rural bias in our election system and the fear about the changing economy. Many Americans, we explained, lost jobs as factories closed and technology changed their workplaces. Because they can’t seem to find work in the new economy, they worry about the future for themselves and their families.

“But he says crazy things,” Arnel said. “How can anyone respect him? He doesn’t seem like a man you can respect.”

These young Bosnians had never seen “The Apprentice” and didn’t know about the beguiling power of a reality TV star to tell people what they wanted to hear and convert their anger at diversity and their declining prospects into votes.

Sighing, we said goodbye and loaded up the car again, this time headed to the coast and the Bay of Kotor in Montenegro.

Read A Trip to the Balkans Part 4