by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

We’ve spent our last few vacations exploring Mediterranean Europe for history and the mix of cultures and religions that centuries of conquest, invasions, trade and forced and willing migration brought. But we’d never been to Greece. The long, cold winter in New York made us crave sunshine and warmth and that was another factor that lured us in June to the cradle of democracy and the birthplace of enduring legends.

The sky was still bright when we reached our hotel on Lycabettus Hill.

From the window of our fifth-floor room, we thrilled to see the table-top of the Acropolis standing out above the Athens low-rise buildings and the Aegean Sea beyond it. And practically everywhere we went, there was another view of it.

Acro means high point and polis means city. The Acropolis is where Athenians practiced self-government for the first time. It remains the city’s central image, historically and visually.

Our small terrace also gave us a sweeping view of Athens and the upscale residential neighborhood that perched around us on Lycabettus Hill.

The city surprised us. The almost bleached-out quality of the sunlight against the landscape of densely-packed pale buildings, which can’t be higher than the Acropolis, makes Athens feel more Middle Eastern than European.

Our friends Israel and Gail Berger had recommended the St. George Lycabettus and we were instantly glad they had. It describes itself as a “lifestyle hotel” and once we got settled, we paused to explore the swimming pool, work-out room and terrace bar, which gave us another great view of the Acropolis.

Then it was time for our first dinner in Athens. Barbara had researched and made reservations for two of our three nights in Athens. The first restaurant she chose promised to show us the Acropolis close-up.

We hopped in a taxi and had our first encounter with an Athens type: a chatty cabbie who spoke good English, loved his city and almost doubled as a tour guide. As we wound down narrow streets, he began by explaining that Lycabettus Hill was one of the best neighborhoods in Athens. When we entered Kolonaki at the bottom of the hill, he waved his hand dismissively. “A lot of expensive shops,” he said. The cab moved slowly through Athens traffic, a lot of it.

As we passed through Styntagma Square, he pointed to the 19th Century royal palace that houses the Parliament and said, “You see this on TV. All the protestors come here. ”

You can also watch the changing of the guard here in front of the presidential palace. It changes every hour, but you’ll find the big show with a full squad of Evzones, the specially trained guards, on Sundays at 11:00 a.m.

A little farther down the road the cabbie slowed and urged us to look to the left into a lighted stadium. “This is the first Olympic stadium when they started the modern Olympics in 1896. It is the only stadium in the world that is all marble. In ancient times, the messenger ran from Marathon to here to tell everyone the Greeks had beat the Persians.” He went on. “You see the u-shape? They kept it open to give a view of the Acropolis,” he said proudly.

He chatted on as he drove up another hill into the Thissio/Makriyanni neighborhood hard by the slopes of the Acropolis. “You know,” he said, “Acropolis means high end. That’s where we are, at the highest point of the city.” He was almost right, and we appreciated his enthusiasm. We thanked him for the great ride and tour and checked in at Strofi. The hostess led us up a series of stairs to its rooftop terrace.

Twilight had deepened and over the houses in the neighborhood, lights shone on the columned Parthenon, the focal point of the Acropolis complex. It looked close enough to touch.

The terrace buzzed with a crowd of people in their twenties and thirties that sat at three long tables.

We thought they’d come from a cruise ship but when we asked one the people who seemed to be in charge of them, she said, “We are a small tech company. We’re team building.”

“Where is everyone from?” we asked.

“All over. Some from Romania, Turkey, Germany, Sweden, the U.K. and the United States.”

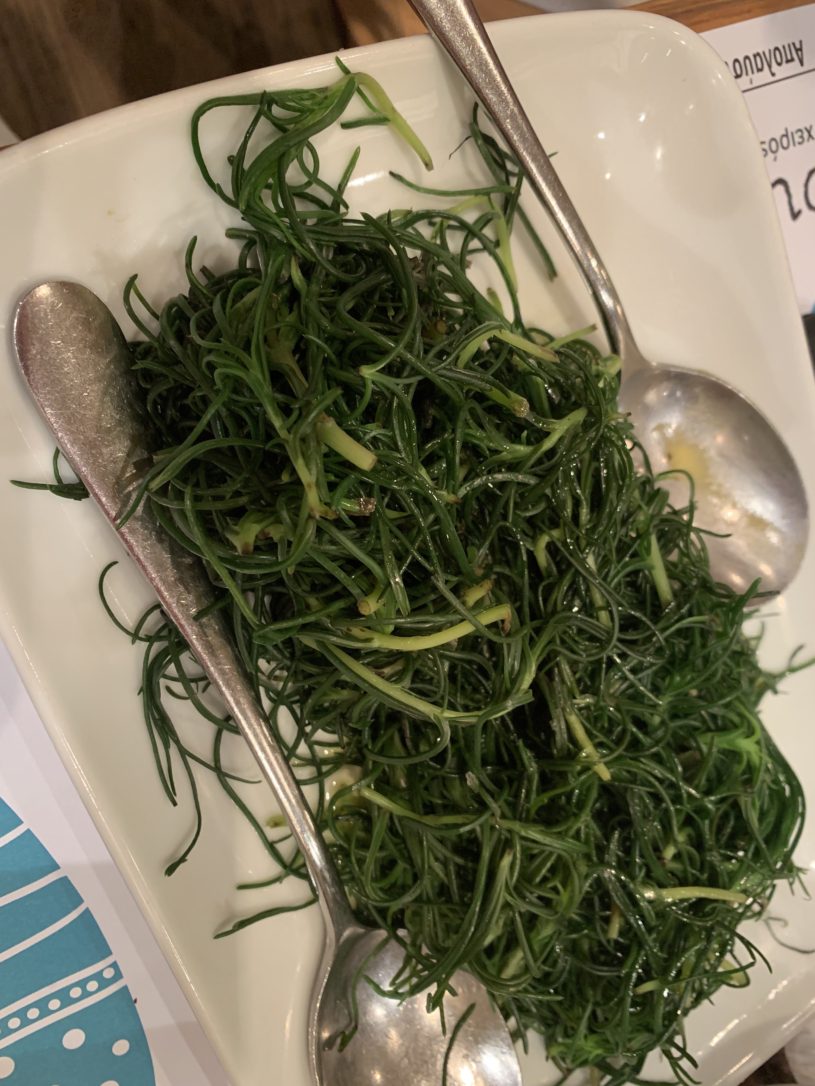

Curiosity satisfied, we turned to the food. Strofi’s traditional Athenian menu favored slow-cooked meat dishes. We started with a smoked eggplant salad for Barbara and octopus in olive oil and oregano for Nick, along with our own tradition, glasses of Prosecco.

Then we moved on to lamb with thyme and rosemary for Barbara and, for Nick, a dish originating on Corfu called sofrito — veal with rosemary, mashed potatoes and roasted cherry tomatoes. We hadn’t learned Greek wines yet, so we ordered a half-liter of the house white, from a grape called moshofilero, and it was just right. Our last indulgence was a piece of walnut cake that even Barbara, who’s usually dessert-averse, wolfed down.

We lingered when the team builders left and we and a handful of other diners had the lights on the Parthenon all to ourselves.

The next morning, we slept late. We made it to breakfast just before the 10 o’clock cutoff and found a corner table on the wrap-around terrace with again a spectacular view of the Acropolis.

You’d expect yoghurt to star at a Greek breakfast and it did, along with honey, an omelet station, lots of fruit, every kind of bread you’d want, and the standard cereals and juices. Necessary and bracing coffee arrived at our table in a carafe big enough for two.

Barbara had arranged for a guided walking tour of the Acropolis through an outfit called ToursByLocals. Conventional wisdom suggested the time to go would be the morning, before the heat rose toward the 90F that was predicted. Our guide said no, the cruise ship passengers all come in the morning and the late afternoon and early evening is better, cooler and less crowded.

So that morning, we walked down the steep streets of Lycabettus Hill and wandered through through the cafes in Kolonaki,

found an HSBC bank to refresh our supply of euros and looked at the boutiques the cab driver had disdained. Many are standard brand name and designer shops. But we saw one with a distinctly local style.

An up-close look at the dress in the center brought the religious iconography into full view.

We decided to head to Piraeus for lunch. We could see Athens’ port off in the distance from our hotel room and didn’t think it would be too far a trip.

Cash-strapped Greece sold management rights to half of its capacity to a Chinese port operator for half a billion euros a few years ago, and China is expanding Piraeus as a gateway to Europe for its goods. We saw it as a destination for a seafood lunch.

The quick trip turned into a slow ride. Like most big cities, Athens chokes on its cars at times during the work day. Our taxi, whose driver spoke limited English, crawled, then picked up speed, then crawled again.

We finally reached Taxidevontas on a quiet street in the Piraeus neighborhood of Keratsini, and took an outside table. Barbara’s research said the restaurant was a local favorite that served fresh fish from local fisherman, and a large and happy group of couples at a nearby table proved the point.

We didn’t have a lot of time before we headed back to meet our tour guide. The waiter asked how long we had and said he would get us the good food and out on time.

We ordered a tarama, the classic white fish roe, a fried octopus appetizer and steamed mussels.

And when we asked for the check, pieces of orange cake and cheese cake magically appeared along with small glasses of lemon sorbet.

We regretted we couldn’t stay longer, but stopped in the kitchen to thank Vicky for a tasty lunch.

After another stop-and-start cab ride, we arrived near the entrance to the Acropolis complex.

Panos Papageorgopoulos, our guide, met us near the booth and we purchased two 30 euro tickets to the Acropolis grounds that would allow us to get into other historic sites during the next day.

Panos, who we learned had just turned forty, bounced on the balls of his feet with enthusiasm. We chose him from the Tours By Locals roster because he has a degree in history, a masters in international relations and is licensed by the Greek Ministry of Tourism to go into the archaeological as well as the historic sites. He seemed just right to help us explore the past in our quest to try to make sense of our present.

He suggested that we start with the Acropolis Museum and go to the site itself when it got a little cooler. This seemed right to us because of the heat and for what we would learn. On our trip to Sardinia in 2018, we visited the archaeological museum first and got a better understanding of the ancient Nuraghi culture whose sites we planned to visit later.

As we approached the museum entrance, Panos said, “Look down there.”

We did, and through clear panels underfoot and from nearby railings, we saw that the museum literally stood atop its history. Panos explained that when the museum’s architects realized the building site lay over ancient Byzantine and Roman sections of the city, instead of filling them in or moving to a different site, they designed columns that showed the sites to visitors and opened them to archaeologists and gave them room to work.

“I was down there earlier, with a few other guides before I met you, to get familiar with it. The archeologists still have a lot of work to do to identify everything,” he said.

We quickly realized that this man loves his job. He told us his passion for history puzzled his father, who didn’t understand why he studied it in school or why he had made it his career.

The museum tickets were 10 euros, or 5 if you visit in the winter. The modern building opened in 2009 in part to display the artifacts dating back to the Bronze Age that archaeologists kept unearthing from the Acropolis itself. The building mirrors the dimensions of the Parthenon, the main structure on the hill, erected as a temple to Athena, the city’s patron goddess. This allows visitors to imagine the structure and its decorations as they were 2,500 years ago when it was built, before the blemishes of time, war, neglect and theft.

As we moved through the collection, we began to understand with Panos’ help the Greek argument for the repatriation of archaeological treasures now scattered in museums worldwide.

The best known of these treasures are the Elgin Marbles, so-called because a horde of full and relief sculptures were removed by Thomas Bruce the seventh Earl of Elgin.

He was Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which controlled Greece at the turn of the 19th Century.

Lord Elgin claimed he took the sculptures, which he later sold to the British Museum, with the permission of the Turkish sultan, but scholars now say there’s no proof of that. Since at least 1982 the Greeks have pressed the United Kingdom to return the works.

The museum highlights what’s missing by displaying gaps and sometimes inserting reproductions. One demonstration of this is particularly powerful. Caryatids are draped female forms used as columns, and six of them supported what’s now called the Caryatid Porch of the Erechtheion, one of the temples on the Acropolis. Panos explained that the statues were likely modeled after young women from Karayi, a town in the Peloponnese, where we were headed.

The museum shows the five still in Athens as they appeared. There’s a missing space for the one Lord Elgin took to London.

Panos said indignantly, “I looked for it in the British Museum and found it in the basement. When I asked why it wasn’t in a more prominent place, they told me they had a lot of things to display.”

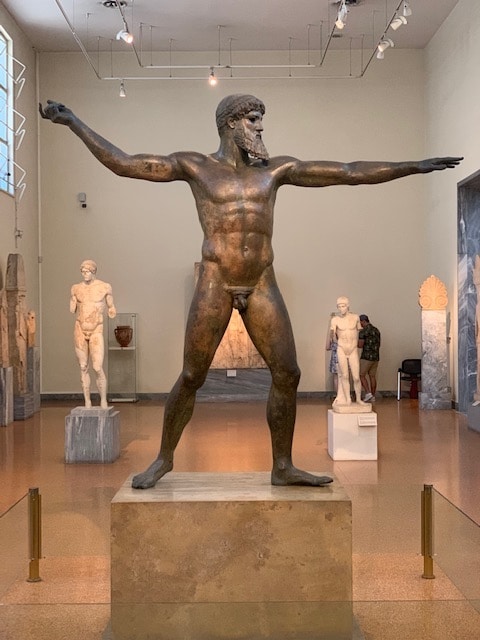

Panos shared interesting details about ancient Greek sculpture. During the time Greece emerged from the 400-year dark age that followed the Bronze Age Mycenaean culture that inspired Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, archaic sculptors shaped male figures that stood stiffly, left leg slightly forward, hands clenched at their sides in the Egyptian style of the time.

The male statues were naked but the female Kore statues were clothed. Both had intricately braided hair that was often colored red.

Around 500 B.C. the stone carvers loosened up a little and classical sculpture became more fluid, and beautifully captured true body forms that implied movement. His knowledge deepened our understanding of how the artistry evolved.

The museum’s top floor is where the Parthenon’s dimensions come into play. It allows full-scale renditions of the temple’s friezes and pediments, combining original artifacts with reproductions and gaps that once again remind you of what Lord Elgin got away with. Panos pointed out the back sides of frieze sculptures that the carvers knew would never be seen, yet left out no detail. “Look at how much care they put in. They were artists,” he said proudly.

Now it was time to climb to the Acropolis itself. Panos led us up a series of steep stone steps and ramps onto the fortified tabletop with its scattering of temples. We passed a theater that is used for performances today.

We walked in the dusty footsteps of Athenians, Persians, Ottomans, Byzantines, Venetians. We had a lot of company but it wasn’t crowded. The sun was still high but the heat was dropping.

The Parthenon rose over us. The temple of Athena Parthenos — Athena the virgin — has been under renovation off and on for years. Pericles ordered it built on a site the Persians had sacked and the nine-year job was completed in 438 B.C.

Time inflicted wounds since then — a fire in the 3rd Century A.D., conversion to a church, then a mosque with a minaret added. The Ottoman Turks, at war with the Venetians since the 14th Century, in 1687 used it to store gunpowder which, predictably, exploded in an enemy artillery barrage.

And an earthquake struck in 1981. Scaffolding raised to work on restoration has seemed, to many tourists, as much a part of the Parthenon as its columns.

Seventeen of those columns march along the sides of the Parthenon, and eight across the front and back, a ratio of nine-to-four. Some people attribute magical qualities to 9-4 rectangles, others snort and laugh. Ratios aside, the architects Iktinos and Kalikrates used visual tricks to make the viewer believe every line of the Parthenon is straight.

They only look that way. Sighting the length of the long wall shows the slight rise in the middle of the base. The columns bulge by centimeters in the middle. And they are slightly closer to one another at the ends. The brain adjusts the picture to straight lines and even gaps.

While work continues on the Parthenon, restoration of two smaller temples, the Temple of Athena Nike and the intricate Erechtheion, is complete.

Leading us to the edge of the Acropolis so we could look down over its surrounding limestone circuit wall, Panos pointed at the foot of the wall to the Theater of Dionysus, the god of wine and the patron of drama. Its semi-circle of stone seats, dating to the 6th Century B.C., makes it the world’s oldest theater. The first audiences saw the plays of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes. With renovations, excavations, and restoration over the centuries the theater remains in use today.

Nearby, we met a couple from Portland, Oregon reflecting, like us, on what they’d seen.

A little after 8 p.m., we retraced our steps down the stone access paths and parted with Panos at the bottom of the hill.

He’d been great company and a fountain of information about the history he loves. If you’re looking for a tour guide in Greece, he’s your man. He speaks German and French as well as English in addition to his native Greek. For all of his enthusiasm we found a wistful quality about him and asked if his father had ever come around from his disappointment about his interest in history. He smiled and said, “Maybe some day.”

Barbara’s research had produced a reservation for the 10 p.m. seating at another restaurant with a terrace that looked out on the Acropolis and the nearby Temple of Haephestus.

A short taxi ride took us to the edge of Adrianou Street, in the Plaka neighborhood. It’s a pedestrian zone, and a few doors in we found the old mansion that was now Kuzina. Chef Aris Tsanaklidis started the place in 1992 when he returned to Greece after cooking all over the word. His menu showed that wide experience.

We decided to find out about the native grape, assyrtiko and ordered a wine from Crete that blended it with athiri, vilana and vidiano grapes.

We split an appetizer of scallops with green pea puree, wasabi and butter sauce. For mains we usually order something different to get as many tastes as possible. But tonight neither of us could resist the spicy tuna with ginger and wasabi over greens.

Both dishes looked great and tasted better. We finished splitting a dessert of lemon curd and blueberries.

Again, we barely made the hotel breakfast after our late restaurant night. Then we climbed in a taxi and asked the driver to take us to the agora. That showed we were Athens greenhorns. Agora means an assembly place, but it also means a marketplace. Our driver took us first to the modern agora, which looked from the street like a flea market where you could buy stuff that fell off a truck. A few blocks farther on we got out at a public square bustling with tour groups, performance artists, and sharp-eyed bystanders. I switched my wallet into a front pocket.

A sign to the site of Hadrian’s Library rescued us. The people there told us how to find the ancient Agora, the city’s original gathering place.

From Adrianou Street, where we’d been the night before, we entered a sprawling hilly site dotted with trees and thin cypresses that speared the sky.

A brutal heat wave was searing Europe to the north, making the 90F in Athens seem balmy, but the shade of the trees in the Agora was welcome nonetheless. Up a hill beyond a statue of the Roman Emperor Hadrian that now showed us nothing but his toga, we saw another temple.

We climbed to it and found ourselves before the Temple of Haephestus, the best-preserved of the ancient Greek temples. That seemed right, since Haephestus was the god of fire and construction.

Iktinos was its architect, and with thirteen columns on the sides and six across the front and back it’s the same rectangular proportion as the Parthenon. And like the Parthenon, it’s had multiple uses since it was built around 450 B.C., including centuries as an Orthodox church and later a museum.

The temperature was climbing, and we wandered quickly around the rest of the Agora and its surrounding park.

We found a taxi and minutes later we mounted the steps of the columned neoclassical facade of the National Archaeological Museum and slipped into the air conditioning.

We decided to visit the section that had the Mycenaean treasures discovered in 1876 by Henrich Schliemann, a self-funded German-American businessman turned archaeologist. What he discovered provided proof that the legendary kingdom was indeed, as Homer wrote, “Mycenae rich in gold,” and that the legendary characters may have been real people. Unlike Lord Elgin, Schliemann donated everything he found to Greece.

A sign for a special exhibition caught our attention and we headed to it, pausing along the way to enjoy some of the spectacular pieces of the permanent collection.

A bronze statue from 140 B.C. of a boy astride a running horse, called the Jockey of Artemsia, recovered from a shipwreck and perfectly preserved, pulsed with energy and captured the will to win.

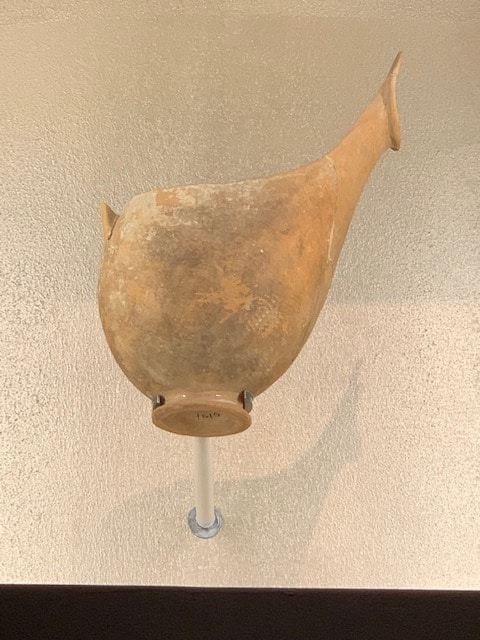

Then we found our way to the special exhibit, “The Countless Aspects of Beauty.” The ancient Greeks developed theories of aesthetics and saw physical beauty as divine. They looked for perfection in all things they created and sculpted gods to embody the ideals they imagine. When it came to building, the “Golden Mean” of the 9-4 rectangle governed the construction of their temples. They strove for simplicity and grace and took care with the proportions of things they used every day and this exhibit displayed objects that told a story.

Some of the perfectly crafted pieces stood out to us. This small pitcher with an upswept neck.

[caption id="attachment_45111" align="aligncenter" width="480"]

Small pitcher from Countless Aspects of Beauty, National Archeological Museum, Athens, Greece. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

We understood why the curators chose this painted vase with perfect symmetry. The objects were more than beautiful. They spoke to the way design and artistry can inject pleasure into ordinary objects.

The show displayed a range of objects including jewelry and fabric and also reminded us that pleasant and intoxicating scent stimulates thoughts, feelings and can envelope you in beauty.

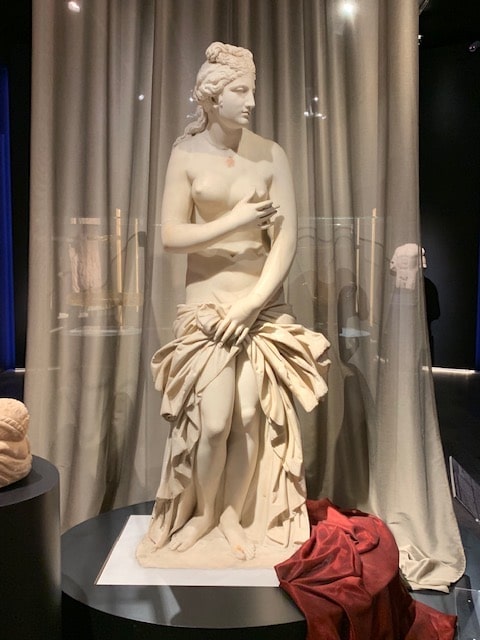

[caption id="attachment_45108" align="aligncenter" width="480"] Aphrodite, Countless Aspects of Beauty, National Archeological Museum, Athens, Greece, Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

Aphrodite, Countless Aspects of Beauty, National Archeological Museum, Athens, Greece, Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

A statue of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty, stood before two flasks of perfume created by Korres cosmetics from ancient recipes. You could lean into individual flasks to inhale and find the aroma that pleased you.

But the highlight for us was the head of a man in contemplation.

His expression invited the viewer into his thoughts, perhaps about beauty, its impact, its brevity, its loss. We left the museum pondering the same questions.

Outside, the waiting taxis were asking a 15 euro flat fare to local hotels. We hailed one passing in the street and reached our hotel with 6 euros on the meter.

We hadn’t booked a restaurant for that night and when we said we wanted fish, the hotel recommended Barbounaki, a ten-minute walk away. The doorman pointed us in a a convoluted direction that sent us twisting through steep, dark streets. On the way we met a New Zealand couple, Ian and Liz Thompson, from Aukland. They were looking for the same restaurant, and we found it together.

We ordered incorrectly. Ian and Liz ordered simple grilled sea bass. Nick ordered red mullet, which turned out to be too bony for his taste.

Barb’s small shrimp weren’t great, either. Her second try with a sushi-like fillet was more satisfying. The conversation was better than the meal and we were happy to have bumped into Liz and Ian.

The next morning after breakfast we taxied to the airport to pick up a rental car to drive to the next leg of our Greek journey, the Peloponnesian peninsula of history and legend.

Thanks for the in depth descriptions and the pictures. This makes me miss Greece (but not the summer heat)

As you can tell, we fell in love with Athens.