by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

By our third day in Lisbon we felt as though we understood the city’s rhythm, at least the tourist heavy parts. We planned to visit the Castelo de Sâo Jorge, which sits at the highest point in Lisbon, and after that go east to the Museo Nacional de Azulejo — the national tile museum.

When we asked directions to the number 28 tram, which would take us to the Castelo de Sâo Jorge, the doorman at 138 Liberdade said, “If you take the 28, watch your wallets and your phones.” His advice echoed warnings we’d seen elsewhere: Portugal’s so popular with tourists that it also attracts pickpockets to prey on them. With that in mind, we headed to Rossio Square and turned left and up a hill to catch the 28.

The 28 was the tram we saw stuck in traffic two days earlier. But on this Tuesday, the single car was packed and the line to board the next one was so long that we decided to skip our visit to the castle.

Instead, we caught a taxi, driven by Joâo Miranda, and asked him to take us to the Museo de Azulejo. We were on the way when a quick — and fortunate — look at Google told us the tile museum would be closed for lunch about the time we’d get there. So we switched again and Joâo turned to look at us, smiled and made a sharp right and climbed a series of steep hills to the castle.

The Castelo de Sâo Jorge sprawls across a hilltop in the Santa Maria Maior neighborhood overlooking a large swath of red-roofed Lisbon, with views to the Tagus River and the 25th of April Bridge.

The Castelo de Sâo Jorge sprawls across a hilltop in the Santa Maria Maior neighborhood overlooking a large swath of red-roofed Lisbon, with views to the Tagus River and the 25th of April Bridge.

Archeologists began digging in the center of the castle in the 1990s and discovered remnants of an iron-age settlement dating to sometime between the 7th to 3rd centuries BCE.

The history about what came next is murky. Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans and Visigoths may have built fortifications here. But it’s believed that Muslim conquerers from North Africa settled on the hill in the 8th century. Archeologist continue to work to build a clearer picture and have found remnants of an 11th century Moorish residential area. In 1147, Dom Alfonso Henriques, the first King of Portugal defeated the Moors and captured the castle. King Alfonso III, who conquered the last Muslim stronghold in southern Portugal, is thought to have built a palace in the 13th century where the castelo stands and the kings who followed built on it. It was known simply as Lisbon castle. But in 1348 King John I, who had married an English princess, named it for St. George, the patron saint of the Crusaders and of England. Subsequent Portuguese kings built up the castle, but in 1775 it was severely damaged by the Lisbon earthquake.

Despite its tumultuous history and all of the tourists who visit, the castelo felt like one of the most tranquil places in Lisbon. Sweet cool air in the dappled courtyard made it comfortable for watching a few of the 40 Indian peacocks, whose ancestors were brought to Portugal by 15th century explorers, roam oblivious to humans. They pecked at the food put out for them by their keepers and wandered through the cobbled plaza.

By the time we’d seen the best of the castelo, it was the afternoon and the tile museum had reopened. We’d had asked the taxi driver Joâo Miranda to wait and now we were back to Plan A. Or was it now Plan C? The two miles on Lisbon’s hilly, twisty streets seemed farther, but we trusted in Joâo’s local knowledge. He dropped us at the door to what had been part of a convent, and we were ready to explore this particular piece of Portugal’s artistic history.

The Museo de Azulejo provides a spectacular history of a national art form. The building behind it is is far grander than this entrance suggests.

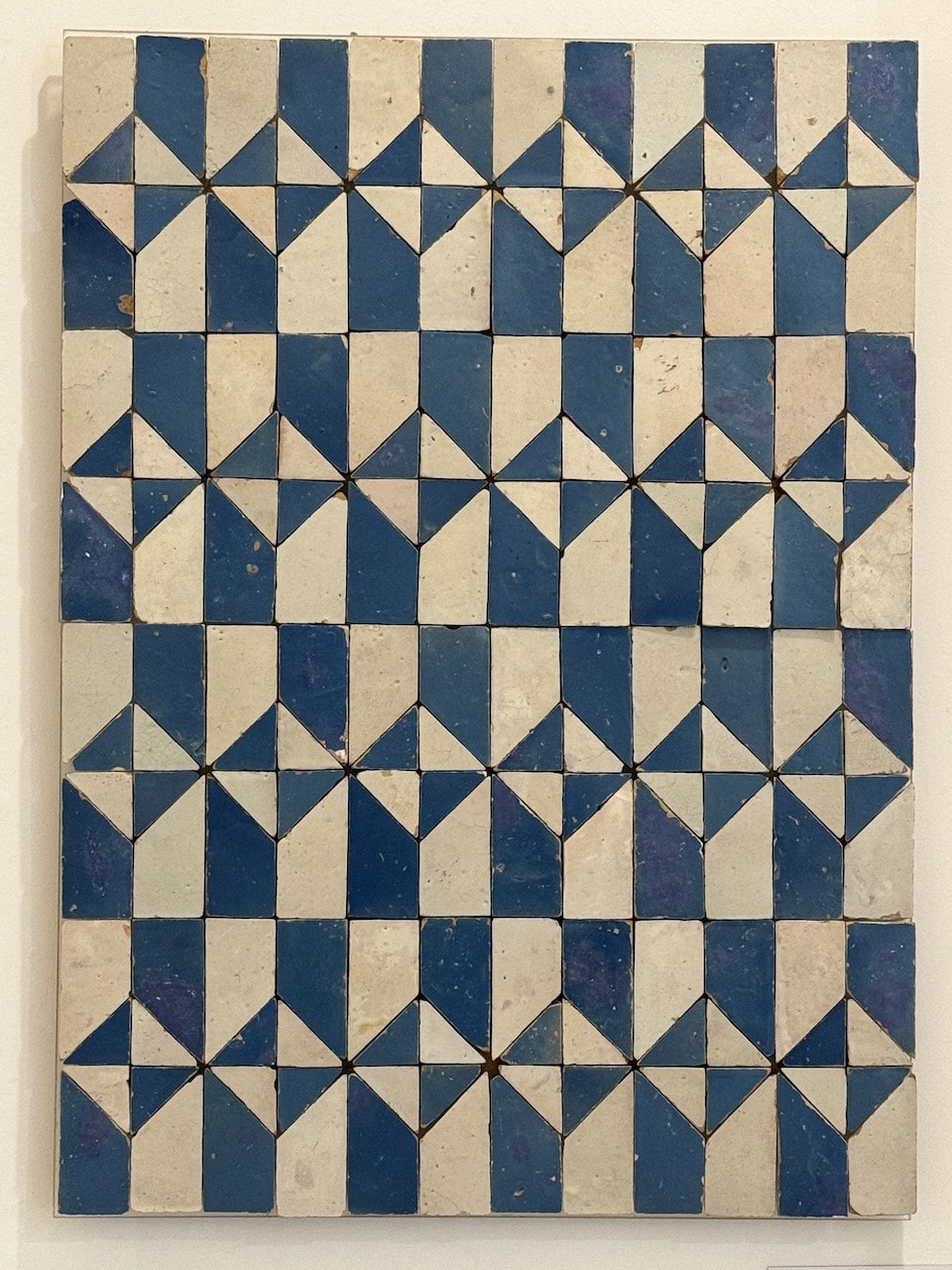

The Convent of Madre Deus was founded in 1509, and the story of Portuguese tile starts about the same time. The word azulejo descends from Arab roots — azzelij or al zulehcha — meaning a small polished stone.

The earliest tiles reflected the Moorish presence in Portugal and Islamist geometric motifs.

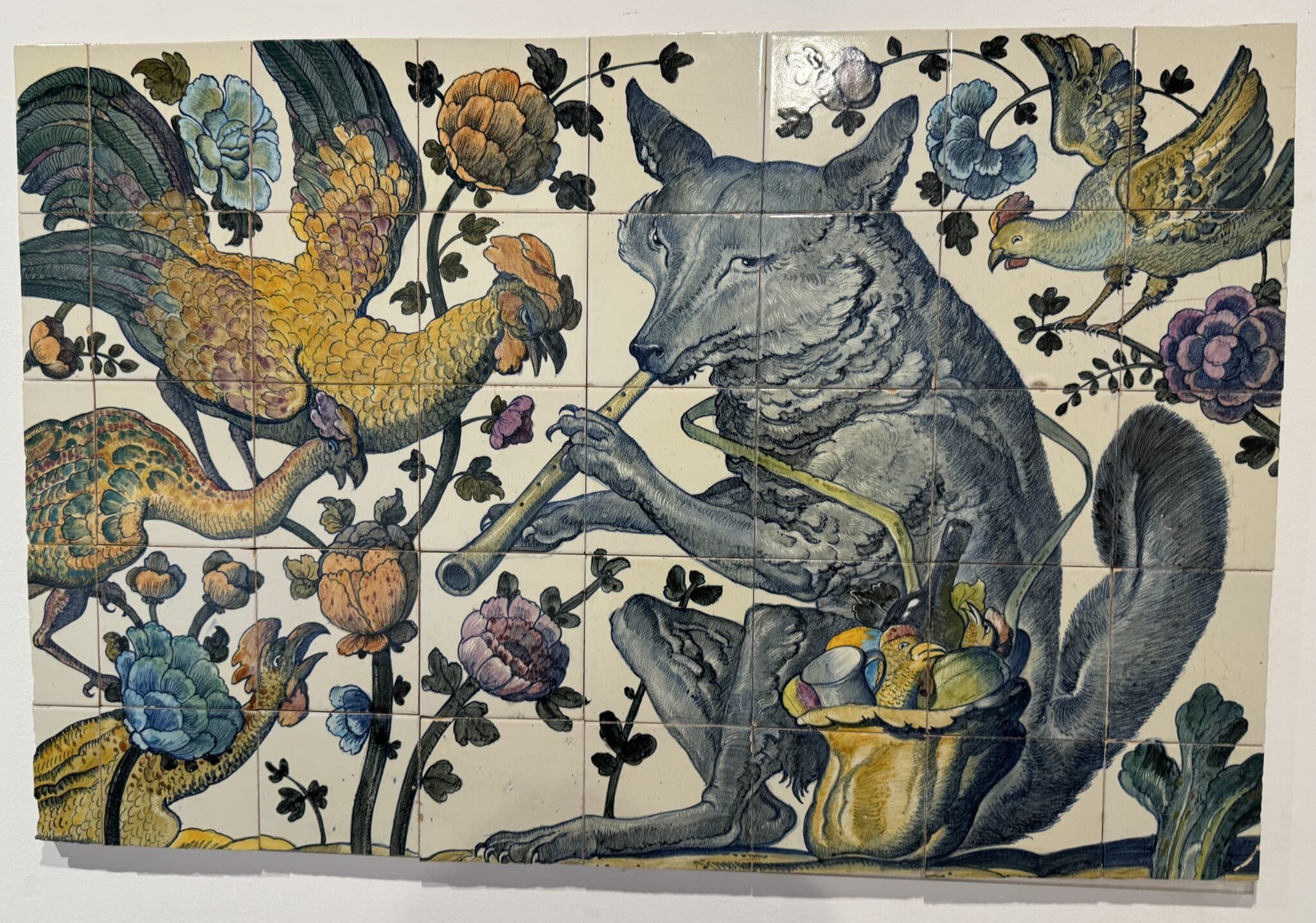

As time went on the tile artists abandoned strict geometry for figurative and religious art.

In the mid-17th to early 18th Century the Portuguese imported the distinctive blue and white Dutch tiles and churches and homes of the wealthy were decorated with them.

Portuguese tile makers may also have followed Dutch Golden Age painting in the 17th century when they created figurative bawdy scenes.

Much of the religious themed tile art decorated sites like this chapel at the convent-turned-museum. If you look at the level of the pews you see the blue-on-white tiles running the length of the room. The work here echoes art throughout Lisbon and the rest of Portugal.

It would be easy to think that the tile art is ancient history, but by the time we weaved through all of the galleries, we discovered that wasn’t true. The art has evolved.

A room on a lower level featured work by contemporary artists.

Enlightened by our new knowledge about Portuguese tiles and their history, we headed back to the city center and grabbed a a late snack at the Pau de Canela pastelaria.

Back at 138 Liberdade, it was almost time for a wine tasting! A French company, Vignobles Austruy, had organized an event in the garden at 6 p.m. The company’s Portuguese representative, Bruno Ramos, led us through the tasting that began with a lovely rosé from Provence.

The estate, Commanderie de Peyrassol, has been producing wine since the Knights Templar were there in the 1200s. Hard to imagine the knights drinking summery rosés, but this one put a smile on Barbara’s face.

The next wine, a port, was from the company’s Quinta da Corte estate in the Duoro Valley, the heart of Portugal’s wine country to the north.

Bruno also poured a Douro Valley red wine Princesa and we began thinking of our trip north to Porto and the Douro Valley in the coming days.

Next came a 2017 Chianti Classico, Tenuta Casenuove from Tuscany. The bottle had the good fortune to sit in front of a neon heart in a window facing the garden.

A Chianti Classico with a heart.

And then there was the Peyrassol La Croix from Provence, the type of red wine we suspect the Knights Templar would have enjoyed.

Feeling great, we opted to stay for dinner in the hotel restaurant. We planned to leave Lisbon in the morning and were excited about heading north and the next part of our Portuguese adventure.