Nick Taylor

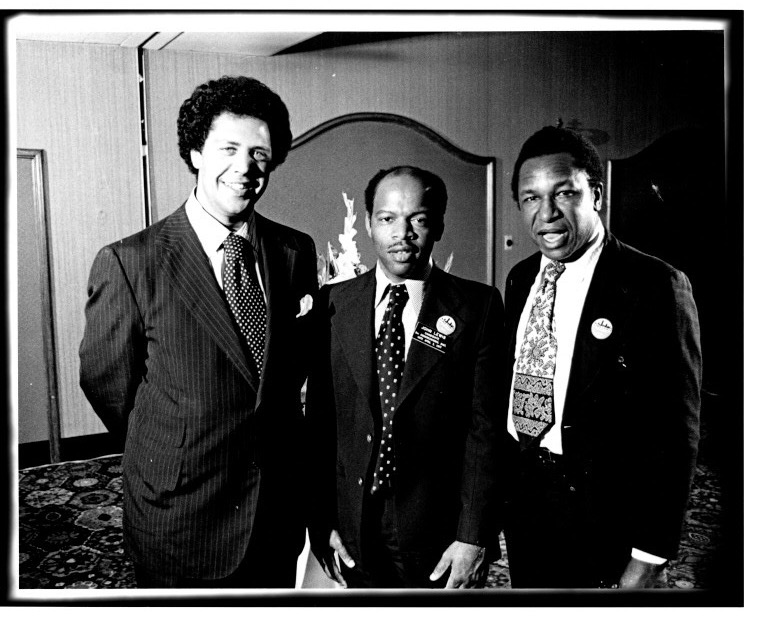

I worked as press secretary for John Lewis during his first campaign for Congress. The election in early 1977 was to fill the seat left by Andrew Young after Jimmy Carter appointed him U.N. ambassador. It was a crazy race.

You would think that in Atlanta John Lewis would be a shoo-in. But that was then, before the best-selling autobiography and graphic novels, before the honorary doctorates and commencement speeches, before the Presidential Medal of Freedom. His fame was narrower. You had to have followed the civil rights movement, which he joined as a teenager causing his elders including Dr. Martin Luther King to call him “the Boy from Troy,” his Alabama hometown where he grew up the son of sharecroppers. Unlike today, few knew of his courage on behalf of equality and voting rights, his lunch counter sit-ins, his Freedom Rides on segregated buses, his march into brutal attacks by Alabama troopers, his fierce address at the 1963 March on Washington. And few knew of his humility and selflessness.

Twelve candidates from both parties were first tumbled into a March non-partisan primary. It included another civil rights leader, Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, and future Republican Representative and Senator Paul Coverdell. Another Black candidate was John’s most vicious attacker. State Representative Billy McKinney said “his wife feeds him cue cards” and worse, “He’s just not smart enough to be congressman.” On the morning of the primary, we reached John’s strip mall headquarters to find it had been broken into overnight, the phone lines cut and the lists of volunteer drivers stolen. These drivers were key to an election in Atlanta. They picked people up from their homes and drove them to the polls to vote. The tradition was so ingrained that without a ride, some just couldn’t get to vote.

But enough of them did. John and the white Atlanta City Council President Wyche Fowler finished in the top two slots. McKinney got 2 percent of the vote, and John and Fowler headed into an April runoff.

John and our team campaigned nonstop moving from one campaign event to another, meeting voters, handing out literature, shaking hands at factory shift changes, and doing interviews. We were always behind schedule because John leaned in and listened to everyone who wanted to talk to him.

Atlanta billed itself as The City Too Busy To Hate and while Maynard Jackson was the mayor and had easily won a second term, there was still a lot of prejudice. This was barely a decade after the Civil Rights Act was signed into law and not enough respect was given. Even though John headed the Voter Education Project in the years before the race, a reporter at the Atlanta Constitution called John a “former civil rights leader.” John objected, saying he still worked for civil rights. He won the Constitution’s endorsement. But Atlanta sanitation workers went on strike a week before the runoff. John took their side against the mayor, and people in the suburbs didn’t like their garbage piling up.

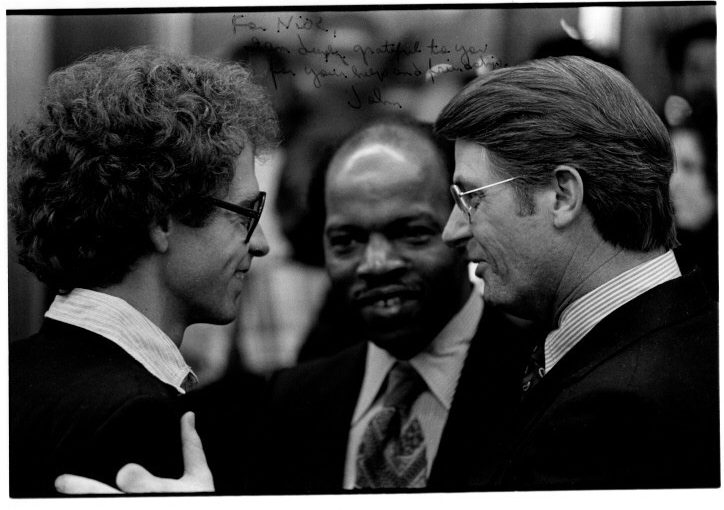

Fowler won the runoff. That night John told the big crowd in a ballroom at the Atlanta Internationale Hotel, “We won tonight a kind of victory. Two months ago, nobody knew who John Lewis was. This is only the beginning.”

After the work of the campaign, we spent time with John and his beautiful, smart and very focused wife Lillian in their art-filled southwest Atlanta home. Their son John Miles was an infant and he kept everybody busy.

John kept his dream of elective office. After the campaign, he headed ACTION, the federal volunteer agency, under Carter and in 1981 won a seat on the Atlanta City Council. When Barbara and I got married in 1983, John and Lillian came to our wedding.

The next year Barbara got her dream job as a reporter for WCBS-TV and we went looking for apartments in New York. The only apartment that compared to the one we owned in Atlanta, was a duplex in a small house on Jones Street in the Village. We saw that it was a competitive situation. Many people came to see, and many people wanted it. The building owner, Harley Jones, an architect told us we’d need letters of reference.

Who would sway him, we wondered. We covered politics in Atlanta and it was a small city where we knew everyone. Then-Governor Joe Frank Harris wrote us a recommendation, but we thought that wouldn’t be enough. Mr. Jones was an African-American man who had clear memories of the civil rights movement. We asked John.

A few days later, Barbara got a call at WAGA, the TV station where she worked. It was Harley Jones. He said, “I just got a letter of reference for you from John Lewis. Anyone who is recommended by John Lewis can live in my building.”

What a relief.

John and Lillian made us a going away party at their home and Julian Bond, Sharon Adams, Tom Houck and other good friends were there.

Two years later, in 1986, John beat Julian in the Democratic primary and went on to win Georgia’s Fifth District congressional seat.

John got the respect that he deserved in Congress and we remained in touch. I took a young friend, Terrence Darby, to Washington to meet John in his office in the early ’90s. The smart teenager was having a lot of trouble reconciling his intellect and blackness. Book smarts weren’t prized on the streets of New York then.

John took the time and gave TD his full attention. That attention is the gift John always gives you.

When Columbia University awarded him an honorary degree — one of some fifty he received before he died — in 1997, he and Lillian invited us to join them for the ceremony and the lunch that followed. His sponsor was at the table, a white man whose name I don’t remember. He said he didn’t know John, just admired him and thought Columbia should, too.

Then last spring, 2019, John received an honorary degree from City College of New York, where Barbara graduated and now is the acting journalism director. While the proud parents and the graduates gathered on seats on a broad lawn in Harlem, I found John inside the Spitzer School of Architecture building waiting to put on the robe signaling another new doctorate. I felt lucky to have the chance to hug him and celebrate his latest honor.

John’s commencement speech to the graduates was his life message to us all: Find “good trouble” to get into. Look around you, see what’s wrong, and do what’s right. And fight every day. Don’t give up. Never give up.

I spoke to John early this year when I learned that he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He said he was starting treatment and felt upbeat about his chances. Not long before he died he was photographed, wearing a mask against the COVID-19 pandemic, with Washington’s Black Lives Matter street mural in the background.

John Lewis never gave up. Remembering him, we remember that we can never be complacent, that we can never assume that rights achieved won’t be stripped away. We have to fight for the things that matter every day.

Loved reading this. He was one of my personal heroes. Miss you two a lot

and hope you are staying safe and relatively sane in our insane world. Susie

Thanks Susie! We are hunkered down trying to avoid all the things we like to do. We hope that you stay well and safe too. Barbara