by Nick Taylor

My prostate surgery was still three weeks away. I tried to keep things steady and in perspective during those three weeks. I wanted to maintain my physical life while I still could. I kept my doubles tennis dates, went to physical therapy, and Barbara and I did our home yoga workouts together. And we made love. How my penis would work when my prostate was gone was a troubling question.

Another big question ate at me. Had the cancer spread? I was scheduled to have my bones and lymph nodes scanned, but not yet. So my life went on as usual with a lot of scary thoughts running through my head. “We don’t know until we know,” Barbara repeated over and over.

I had a literary agent named Al Loman who liked to say, when I badgered him to know if we’d heard from a publisher, “No news is no news.” That was the case here, too.

There was plenty to do in the meantime. I gave up details of my body chemistry in vials of blood and urine. I was plastered with electrodes for an electrocardiogram to make sure my heart rate was steady enough for surgery. Blood pressure cuffs squeezed my arms and legs to see if I was likely to stroke out.

The two scans were scheduled for the same day, January 25, a Tuesday. I reached the huge NYU Tisch Hospital complex on First Avenue at 2 p.m. Inside, I followed a maze of color-coded pathways and ended up in the Kimmel Pavilion at the corner of 34th Street. There Christina Comaniciu, a technician in the Nuclear Radiology department, jabbed one of my veins and injected a radioactive solution. “Are you Romanian?” I asked. She was, and we chatted, both of us masked, about the country that Barbara and I had visited a few years back to explore her father’s family’s roots. Then she sent me off with a reminder to be back at six. It was about two-thirty.

The site of my second appointment, NYU’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, was a few blocks west. I walked up a rising 34th Street toward the ridge line of Manhattan, looking from above my mask at other New Yorkers also masked for going on a third year now against the latest COVID variant that was extending the pandemic. The city seemed exhausted. Trash littered the gutters and homeless people huddled under scaffolds. I wasn’t the only person on the street with reasons to be anxious.

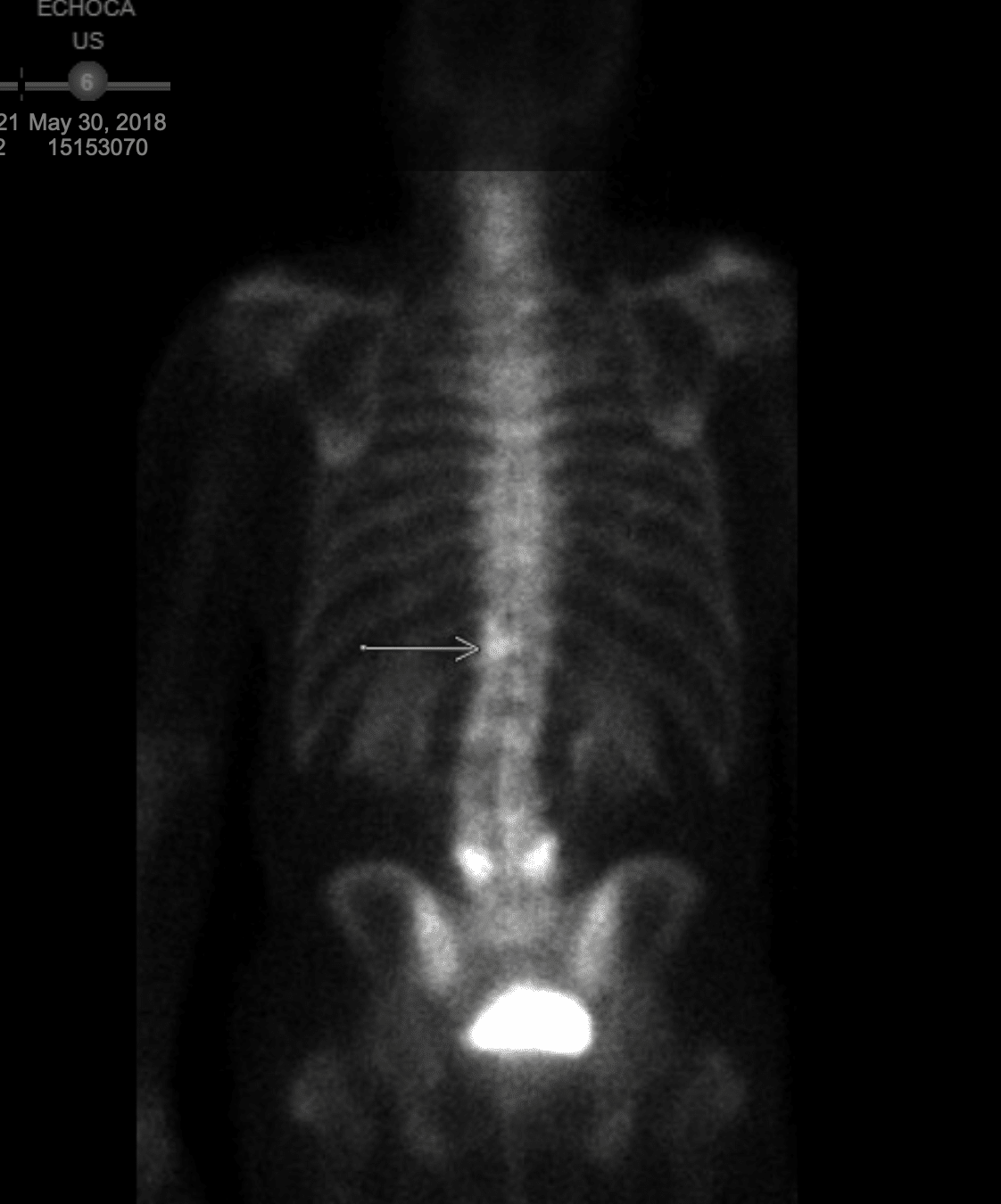

I arrived around my three o’clock appointment time, changed into a gown, and received an injection of more radioactive liquid. Then I was shunted into a room for the seventy-five minutes it would take for the solution to be readable. I had brought a book but was told to leave it and my phone in the locker with my clothes. A radio played inaudibly. The seventy-five minutes stretched to ninety and then more. Finally I pushed the call button. An attendant came in and turned if off. “I understand it’s a long time, but there are other patients,” he said, and left again.

At last I was pushed into the room where the PET scan machine waited. Cradled in a concave stretcher, I entered the machine’s white donut hole of a mouth. The scan took over half an hour, and when I was dressed and released it was after seven. As I walked back east on 34th Street I saw a message on my phone that the bone scan people had tried to call me a little after six. It was seven-thirty when I got back for the bone scan, and nobody was there.

I finally tracked down an attendant who seemed puzzled to see me. After calling the doctor he relayed that the bone scan couldn’t have been done anyway, that the Flourine 18 from the PET scan would have made the bone scan impossible to read. A master stroke of scheduling, I thought.

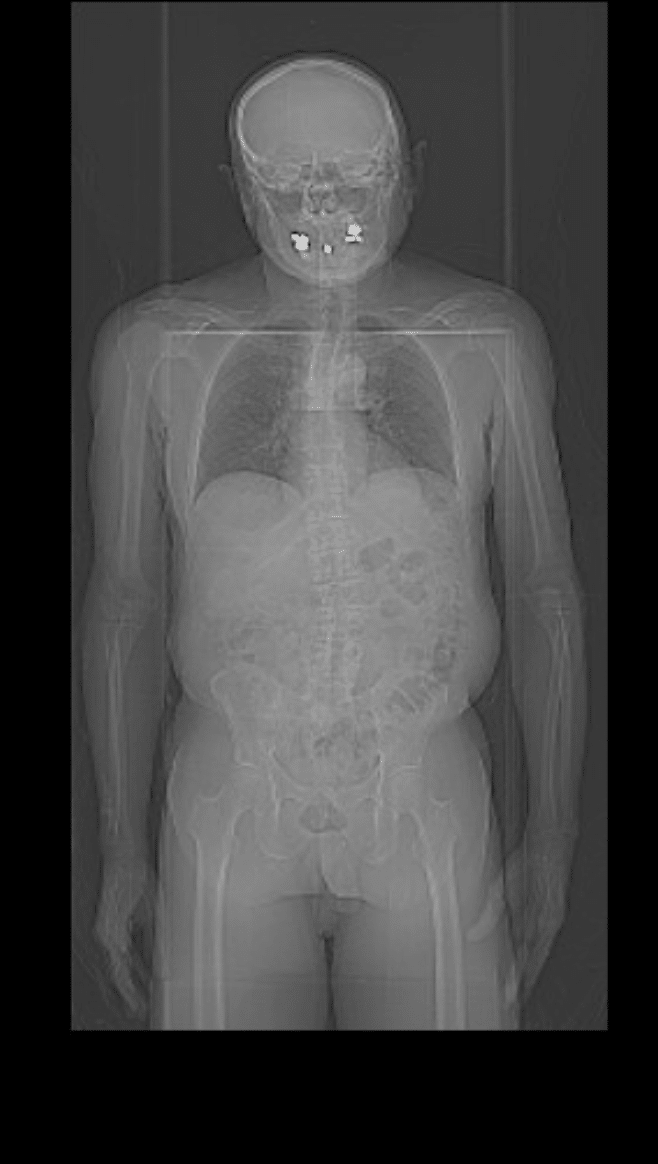

I got a new appointment for that coming Saturday. A snowstorm started overnight and I walked through slanting snow on slippery sidewalks from the subway and reached the hospital at eleven. The radiation tech, named Mathu, told me it had taken him two hours to get there from his New Jersey home. He jabbed another vein and injected me with Technetium 99. “Don’t worry,” he said, “It has a short half-life.” Then I waited.

Outside the windows, the snow blew up First Avenue. I drank coffee and read Arnaldur Indridason’s Jar City, an Icelandic noir about human organs, genetic disease, and murder. I was called for my scan at two. In the scanning room, I changed into a gown and climbed onto a flat table that moved under the scanner.

I spent the next hour under the gaze of a variety of screens, overhead and on each side. Sometimes the screens moved, sometimes the table moved me at microscopic speed in and under them. It had stopped snowing when I finished. I wished Mathu good luck driving home, and then I headed for the subway.

The NYU Langone MyChart tells you when you have new test results. They come to you Joe Friday style, just the facts, relayed in dense medical language. The PET scan results came first. I was alone when I logged in and held my breath as I read, “No evidence of PyL avid lymphadenopathy.” I had to look it up. That’s a swelling of the lymph nodes, a lack of which I took to mean that they were cancer free. I sighed with relief, but the bones are a prostate cancer’s first metastatic target. When word came that those results were posted, I again read the medical language with bated breath, hoping I’d be able to interpret it. The words that said, “You’re clear” were these: “no evidence of osseous metastases.” I breathed again. When Barbara got home from teaching at the City College of New York we hugged and jumped up and down. She insisted that we dance.

That meant that prostate surgery — in clinical terms a radical robotic prostatectomy — was the right choice for me.

On Thursday, February 3, Dr. Samir Taneja‘s office called to say I’d be first on his operating table the next morning.

A driver from the car service we use waited on the street outside in the pre-dawn dark. We climbed in in pelting rain and were at the hospital by six. When I checked in using a tablet on the reception desk, I got a bracelet that said John Taylor. “Tell them that’s not your name,” Barbara said. She’d been urging me to let MyChart and Taneja’s office know that my name is Nick, although the official version is John Nicholas Taylor. “It doesn’t matter,” I told her. “If John Taylor gets cured of prostate cancer, Nick Taylor will be happy for him.”

About ten minutes after we checked in, a nurse came out with a bunch of charts and then called names. Those she called lined up single file, like elementary school, and followed her in like little geese. I was off-ramped into a small, pleasant cubicle. I changed into a large hospital gown and yellow socks with non-slip treads and climbed into a comfortable contoured chair. Once I was settled they let Barbara come in. She teased me about the shower cap on my head and took a couple of photos.

A pleasant young anesthesiologist interrupted our nervous chatter. He asked me about allergies and explained what the anesthesia would be like as he put an IV port into my left arm.

I have to admit that I was nervous. Dr. Taneja, wearing casual street clothes, came in a few minutes after the anesthesiologist. “How are you feeling?” he asked. “I guess I’m ready,” I said. “At least I’ll be in out of the rain.”

This was idiotic. I admit it. When Barbara said, “What?” I laughed and the doctor shrugged and walked out of the little space.

A few minutes later, a nurse came to walk me to the operating room.

It seemed crowded, at least six people in scrubs working. I hoisted myself onto the operating table. The anesthesiologist hooked up my IV and that was the last thing I remembered until I woke up in the recovery room.

The prostate surgery lasted about three hours and forty-five minutes. Barbara had gone home to wait for a call from the hospital. When her phone buzzed, Taneja was on the line. He said, “The surgery went well. He is doing fine. You can probably see him in an hour or so.” She gushed, “Thank you. Thanks so very much.”

I was in a cubicle in recovery with a woman behind a curtain next to me moaning. I had my book on the tray table when Barbara came in. “You look great,” she lied, and kissed me. A nurse checked my blood pressure. It was 189 over 96, way higher than my normal 120 or so over 70. But I didn’t feel it. Whatever drugs they gave for anesthesia and to dull the pain made me feel happy and light. So Barbara and I chatted about nothing and then the nurse came back to say that Barbara had stayed long enough. She could join me in a room once I was settled.

About an hour later, I was settled in the room. It was early afternoon. Rain still fell and out the large window Queens and Brooklyn high rises loomed across the East River gauzy in the rain.

And Barbara was back. “How do you feel?” she asked. “I’m still figuring that out,” I said. I didn’t feel as loosey goosey as I did in the recovery room. I was conscious of the catheter in my penis and I felt a restricted band across my belly at the level of my navel. That was where the surgical incisions were, six of them where tiny robotic instruments went in to be manipulated by Taneja from images relayed to a computer screen. They told me where they were the first time I tried to lift myself without assistance, and from then on I used the bed control buttons when I wanted to sit up.

I was grumpy. Barbara tried to distract me, pointing out the ferries nosing in from across the river and departing to return. “Look. It’s beautiful,” she said. “It’s gray and miserable,” I grumbled. “No, it’s really lovely,” she said, adding “in its way.” We always say, “In its way” when we talk about something that is beautiful but too harsh to be inviting.

A nurse came in and took my blood pressure. “Oh, it’s still high,” she said. All my other signs were normal. An attendant came in and put some water and tea and apple juice and a carton of Ensure on the table. Another attendant came and helped me out of bed so I could walk around the ward with my catheter bag, wheeling my IV pole. Back in the room, I mindlessly watched CNN without the sound.

Barbara said she’d be back to get me in the morning. The night nurse kept checking my blood pressure, which dropped but only slowly. I didn’t feel it physically, but I knew I was anxious about what was next. I’d have the catheter for a week. I could feel the holes in my belly that were held shut with skin glue. A return to what I thought of as normal life seemed distant.

The next morning the sun was out and I couldn’t wait to go home. I called Barbara six times, each time reporting that I was waiting to get the final discharge from Taneja.

A physician’s assistant from Taneja’s office had told me I’d be discharged between nine and eleven. My nurse heard that and rolled her eyes. “It won’t happen before noon,” she said. I walked around the ward again a few more times, and climbed up and down a set of three small stairs.

Once the staff reached Dr. Taneja and he signed off on the release I called Barbara to pick me up. The online discharge documents took forever for the nurse to complete. I took off my gown and put on the clothes I’d worn to the hospital, then listened as the nurse told me things I’d need to know. Catheter 101 was the bulk of it, but another vital piece of information had to do with farting: “Don’t eat solid food until you start to pass gas.” So flatulence now was something to look forward to.

A driver called Jose from the car service waited downstairs. When I got in that car, the rest of my life had started. How different would that life be than the one I knew? I wondered.

To be continued.

Thanks for sharing. Thinking good thoughts. Looking forward to Savannah.

Dean