by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

Getting on a sailboat in the Virgin Islands felt like a dream. We hadn’t done a bareboat charter, sailing by ourselves, since 2017 and we hoped that we were still strong enough to sail a 37-foot boat. We learned a lot.

Most people plan ahead and book a bareboat sailing trip months, or even a year ahead. But a week before Christmas, we looked at each other and said, “Let’s try to find a boat for the first week in January.” Nick started emailing and discovered the charter companies on Tortola in the British Virgin Islands had no boats that we could sail. All our experience was on monohulls, and the catamarans that were available were all too big for us. We took a shot and contacted the charter booking agency Ed Hamilton & Co. Their salesperson, Lynne Harbison, found that Waypoints in St. Thomas had a 37-foot Dufour available.

We rhapsodized about blue skies and green water and almost felt the wind and the sea caressing our skin. Nick filled out all the information about his captaincy qualifications and our sailing history. But we learned quickly that because we hadn’t sailed for several years, and maybe because we are older sailors, Waypoints wanted us to hire a captain for the first day to check us out. They would find the captain and we’d pay him directly. It seemed like a fair test and we agreed

American Airlines out of JFK took us directly to St. Thomas on January 4 and we enjoyed the tourist’s board’s welcome.

That afternoon we were sitting in the cockpit of Easy Wind looking out into the Charlotte Amalie harbor from the dock in Frenchtown, eating the Faicco’s sandwich we had brought from New York.

We planned to sail the next day, Sunday morning, and our first task was to provision the boat.

Marsha Coward, the Waypoints base receptionist, recommended we shop at the Pueblo supermarket and called a taxi for us. The big store had everything we needed except eggs, and we guessed that holiday demand and Bird Flu made them scarce. A taxi driver took us to Moe’s, a store that’s a yachter’s favorite, and it was the same story there. We shrugged and headed back to the boat to stow our provisions minus eggs.

Little things, like the egret wading along the dock, made us feel that we’d made the right decision.

That evening we took a short walk to Oceana, a restaurant on a point of land overlooking the water.

It was crowded but we found a seat at the bar where Mitch, the bartender, was good company. We shared dishes of ceviche, garlic shrimp, crab cake, and focaccia. Back at the boat, we went to sleep in the bow berth excited — and a little nervous — about what tomorrow would bring.

Our captain Bobby Durkin showed up at 8 a.m., and he looked the part. His scraggly beard and long floppy hair beneath his cap brim gave him the air of an Irish deckhand who might break out into a sea chanty any minute.

Bobby works with Waypoints in the Virgin Islands, but is based out of St. Petersburg where he teaches sailing. His confidence and his willingness to take us as we are, a couple of older sailors who’ve seen spryer days, without judgment, made us feel confident.

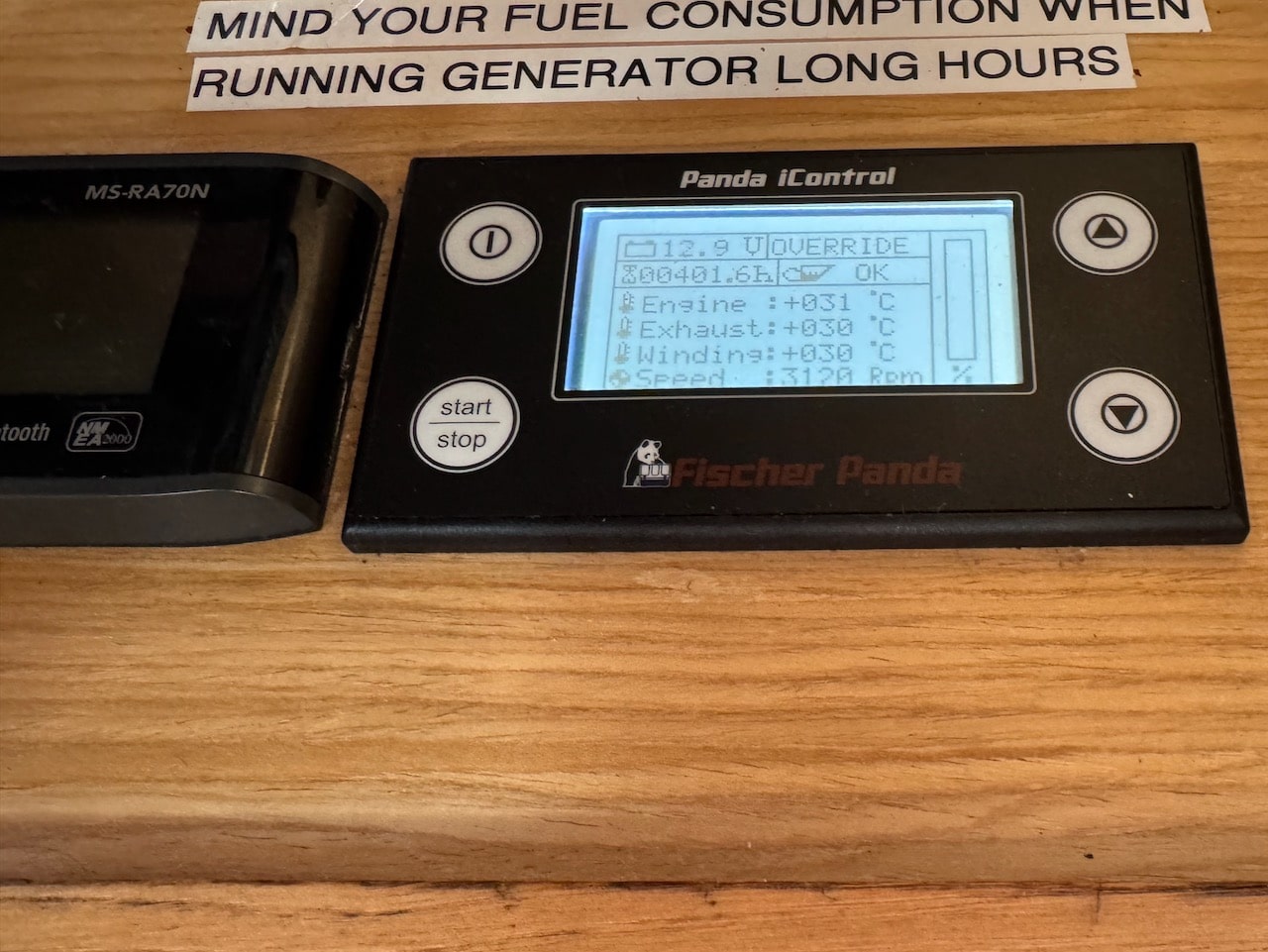

He charmed us immediately and started our briefing below deck, where he began the refresher course showing us how to turn essentials like the generator on and off.

He went through the instrument panels and switches and showed us how to check the engine oil, use the head, turn on the air conditioner and use the desalinating water maker. In the galley, he explained how to turn the stove’s propane on and off and showed us where the fire extinguishers lived in case there was a fire.

By late morning we left the dock and headed east out of Charlotte Amalie. It was approximately nine nautical miles on a choppy-blue green sea toward Cruz Bay at the west end of St. John, St. Thomas’s sister island. We got the full view of the south coast of St. Thomas, with its small beaches, harbors, hotels and condos.

The National Weather Service broadcast a small craft warning for Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands with waves running from six to 10 feet. That’s a lot. The wind blew between 20 and 30 miles an hour. Bobby wanted to reach Caneel Bay before 3 p.m. so that we would be sure to get a mooring in the anchorage. That had us motoring and bouncing against the waves until we reached a cluster of islands, Great St. James Island, Little St. James Island and Dog Island, which opened onto Pillsbury Sound facing St. John and Cruz Bay.

Nick was at the helm steering the boat when Bobby directed him to head through a relatively narrow gap between St. Thomas and Great St. James Island. Once we got into Pillsbury Sound Bobby said, “Now it’s time to sail.”

Aah. Here was our sailing test and on this Dufour, the learning curve was steep. First we raised the mainsail, with Barbara at the helm.

Nick wrapped the halyard and cranked the winch to raise the sail.

The last sailors aboard Easy Wind had left the mainsail reefed, which meant it was smaller than full and wouldn’t overpower the boat in the winds we had.

But a Bimini top over the center of the cockpit, no doubt installed as sun protection by the boat’s owners, meant we couldn’t see the mainsail as we tried to raise it. Heading into the wind meant the sail’s battens shouldn’t snag on the jack lines that steered the sail into its boom cradle when it was being lowered. But it happened anyway. We needed eyes on the sail , and Bobby was quick to take down the Bimini so we could raise it right.

Then we got ready to raise the genoa (genny) but realized that the boat was set up for a single-handed sailor and the sheets for the main sail and the genny shared the same winch. This is significant because to trim a jib or genoa to make it catch the wind and fly smoothly, you need to tighten its sheet. That’s the rope attached to the jib’s clew — its rear corner. Tightening it means using a winch in order to adjust it.

The set-up on this boat required you to clear the main sail off the winch if you wanted to tighten the genny. Bobby suggested that with the main sail flying smoothly, we could forget the main sheet and focus on getting the genny sheet around the winch. That made working the sail much easier.

We tacked back and forth between Caneel Bay and Lovango Cay to the north-northwest, with Nick at the helm and Barbara working the sheets. We began to enjoy the feel of Easy Wind and Bobby said, “I think the two of you can sail this boat.” Whew! We smiled at each other.

We saw that Easy Wind could make 6 knots easily, even when close-hauled. This would give us good sailing if the same weather conditions held. We went back and forth about six times, recapturing our skills. It was exhilarating!

When it came time to catch a mooring ball to hold us in place, we had to lower the sails and start the motor. Catching a mooring ball often challenges us, and other sailors. First you have to attach lines to bow cleats on the port (left) and starboard (right) sides of the boat.

Bobby showed us the correct technique.

Nick took the helm, and Barbara took the long metal pole with a hook at the end known, not surprisingly, as a boathook. The idea is the driver of the boat nudges close to the mooring and the person with the pole reaches down and catches the line attached to it that’s called the painter and hauls it up. Then the line on the boat gets pulled through a round hole, the eye, at the end of the painter.

That white thing is a mooring ball. Imagine catching a line on it with a hook?

Again, that’s a lot and it’s tricky. Bobby had Nick put the boat in neutral, but on our first pass Barbara missed the mooring ball. There was back and forth then about who should drive the boat and who should catch. So Barbara took the helm. Nick missed the mooring ball. Barbara took the pole again and this time Nick steered her close enough to catch it.

But pulling it up takes strength and Barbara realized, this is where her age showed. She wasn’t strong enough. “Come help,” she called. Bobby stood back while Nick came forward and helped haul in the mooring and thread the line from the boat through the eye of the painter. And then we had to add a second line from the other side, which was slightly easier. Now we had two mooring lines holding us in place and we felt safe.

While we had Bobby we wanted to practice raising the main sail more smoothy than we had done at first, and so we did. “We’re just taking the rust off,” he said over and over again as we polished our skills.

It was close to 5 p.m. when the three of us got into the dinghy to take Bobby to Cruz Bay around the point from Caneel Bay to catch a ferry back to St. Thomas.

Cruz Bay at the west of St. John has a population around 2,700 and lots of tourist shops. While Cruz Bay is an anchorage with docks and some mooring balls, Waypoints put it on a list of no-go zones for their boats because it is generally too crowded and could be dangerous. Bringing the dinghy in was fine, and you could beach it, or tie it up to a small dock.

We had forgotten to get swim flippers at the Waypoints dock. So after we said goodbye to Bobby we went into the Beach Bum shop and rented two pairs of flippers for the week for a pricey $50. Then we dinghied back to Easy Wind smoothly moored in Caneel Bay.

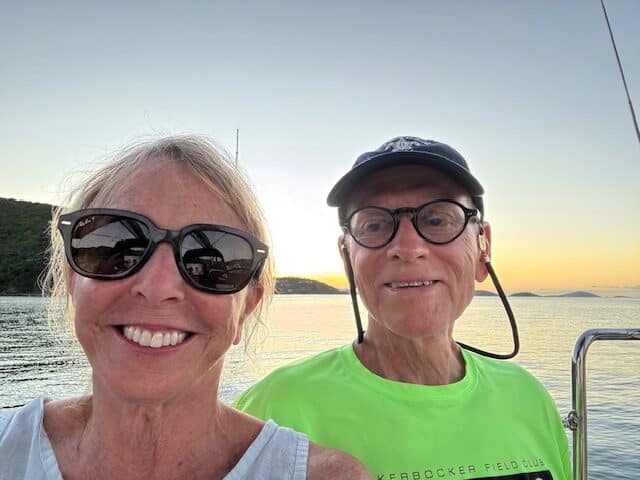

“Now let’s kick back and have a drink,” Nick said. We poured ourselves short vodkas and stretched out on the cockpit seats. The sun dropped low and we watched the lights on St. Thomas to the west blink on as it set. It was close to dark by 6 p.m. Atlantic Standard Time. Two days ago we’d been freezing in New York.

We pan-fried steaks in the small galley and ate them in the cabin, listened to Bill Evans and talked about the day. We’re readers and it was easy after dinner to stretch out on the comfortable banquettes and get lost in our books for a while before tucking into our berth for the night.

Caneel Bay has rough water even at the best of times.

Ferries approaching and leaving Cruz Bay leave boat-rocking wakes that test your sea legs and can make objects airborne if they’re not tied down. Being rocked to sleep is one thing, being rocked awake in the morning was something else. “It feels like someone is pushing me in a hammock,” Barbara said when sat up suddenly.

It was a beautiful morning even if it was rolly. We tried to enjoy breakfast on deck, had some toast and yoghurt and decided to head to a calmer bay if we could find one.

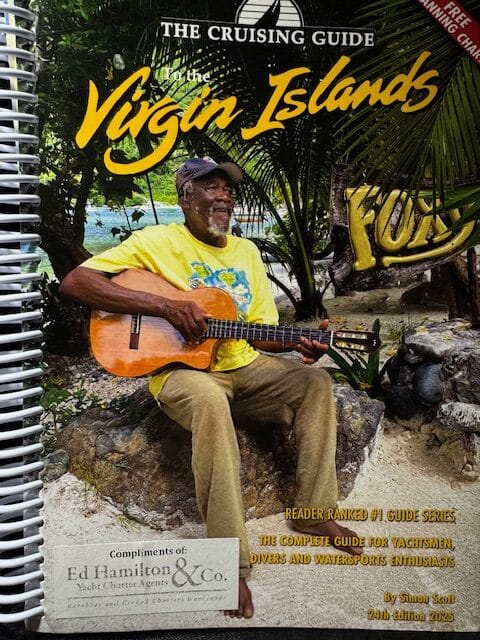

The Virgin Islands Cruising Guide, our onboard Bible, told us Leinster Bay was “well protected and quite comfortable.” It was on St. John’s north shore and the charts showed us we could get there easily. We started the engine, dropped our mooring, and steered into six-foot swells pushed at us by a stiff wind out of the east. The sky was clear and the bumpy water was a brilliant blue.

Our route took us north and then northeast. Leaving Caneel Bay gave us a view to the north and we saw on the horizon Jost Van Dyke, an island in the BVI we’d visited. Its famous beach bar. Foxy’s, attracts a lot of visitors and in the anchorage there at night, you hear the fun if you’re not on shore participating.

St. John is another story altogether. Peaceful.

The hilly, green St. John shoreline slid by on our right side and we steered through the Windward Passage to clear Mary Point. This anvil-shaped jut into the water is northernmost St. John. A little way farther, Leinster Bay opened up off our starboard bow. Barbara fretted that Nick sailed too close to Mary Point. “Look at the green water. Look how light it is. Maybe steer more port,” she must have said five times. Nick said, “It’s fine. The chart says we have enough water,” and he held his course.

When we rounded the point, we saw that other sailors, too, were seeking Leinster Bay’s comfort and protection. We saw several masts and thought at first there might not be any moorings left. Once we got closer we saw plenty. Now our redeveloping mooring skills came in handy.

Nick steered the boat and Barbara tried for the mooring. She missed the first two pickups, but then we saw another mooring ball closer in and more sheltered. Nick put the boat in neutral and Barbara felt determined to snag the mooring line. She reached down and slid the hook under the line and pulled. She got it up to the rail, but couldn’t hold it and secure it with the line from the boat. She realized she wasn’t strong enough. Nick came to the rail and while she held the mooring, he tried to slide the line through the eye of the painter attached to the mooring. The strong current rocked the boat and the mooring and the mooring yanked the boathook into the water.

Fortunately, boathooks float. Barbara took the helm and Nick rushed to untie the dinghy to retrieve it, but he slipped and fell in the water. While he climbed back into the boat, voices from the bow called to us from two dinghies. “Can we help?” said a guy who later identified himself as Dan from near Four Corners, New Mexico.

“Yes,” Nick called back. Dan’s friend Bob in the other dinghy had already picked up our mooring line and secured it to the mooring.

We tossed the second mooring line to Bob and he secured that one. Nick, in the meantime was soaking wet and asked the pair, “Can you maybe find our boathook? I think it’s over there.” He pointed.

The two raced off in their dinghies, found the boathook and brought it back. Whew. A boathook is the most necessary tool aboard a boat; you can’t get moored without it. “Come to New York and we’ll buy you dinner,” we said gratefully.

Resilience is pretty important in everything, especially sailing. And so lines in place, we lowered the swimming platform at the stern, put on our swimsuits and our snorkels and our rented flippers and swam around the boat to see what we could see.

The strong current stirred up the water and snorkeling wasn’t good. The water, though, felt wonderful. We hosed off with the deck shower and sat back and enjoyed the show; the sky burst into color as the sun dropped slowly over the islands to the west. That evening, as the generator ran the air conditioner to cool the cabin, we baked chicken in the propane oven, listened to a mix of Steve Earle and more Bill Evans and enjoyed the calm.

The next morning, Tuesday, we lolled over breakfast in the cockpit. We didn’t feel like moving the boat, and the ruins of an old Danish sugar plantation beckoned from ashore. The Annaberg plantation, what was left of it, was in the Virgin Islands National Park. We bundled into the dinghy and motored to a corner of the bay.

A few yards away, we came to a group of people seated back from the water in the shade, eating lunch. They were a curious, non-touristy looking bunch and Barbara asked who they were. They told us they were volunteers clearing trails and doing other work through Friends of the Virgin Islands National Park. All of them came from the United States, including one from Franklin, North Carolina, near Nick’s hometown of Waynesville in the NC mountains.

The one person who worked for the National Park Service told us how to find the trail to the Annaberg Plantation. We walked a mile along the pebbly shore and through the woods and reached a spot that pointed us up a road to the plantation’s parking lot and entrance.

We walked into a landscape of crumbling stone buildings. One had been a windmill used the crush the sugarcane to release its juice. Other buildings housed the 600 slaves that worked the planation for their Danish masters. By 1733, records indicate that there were 1435 men and women, originally from Ghana, enslaved on St. John.

It all told a sad and all-too-familiar tale of the human cost of sugar. In 1733, slaves organized a well-planned revolt that by all accounts killed colonists, and took over the island. The Danes failed to get help for nine months until the French sent a fleet from Martinique. Twelve of the rebellion leaders jumped from a cliff at Ramshead and committed suicide, according to the National Park Service.

When slavery was abolished in Britain and its colonies in 1834, some slaves swam the two miles from St. John to Tortola in the British Virgin Islands.

The Danes clung to slavery until finally, in 1847, the government announced the practice would be phased out over twelve years. That triggered another revolt in 1848 that forced the governor general of the Danish West Indies to capitulate and free the slaves immediately. Emancipation ended the island sugar industry in the islands, and in 1917 Denmark sold St. John, St. Thomas and St. Croix to the United States.

Wandering among the Annaberg plantation buildings we saw, on a tiny stone building, a small faded sign that announced “BREAD BAKING.” Inside, we met Miss Olivia. She was demonstrating how cinnamon-flavored “dumb bread” was baked in the traditional ovens. We had some and washed it down with sweet tea. Her personality cast a brighter light on the plantation’s history.

Ms. Olivia — actually Ms. Olivia Christian, a native St. Johnian and a mother of four sons — is one of several people doing cultural demonstrations at Annaberg three days a week. They give visitors an up-close look at island life before tourism was king. Miss Olivia explained that she’s proud of the history of the Black people on St. John and the other Virgin Islands who revolted and ultimately became the property owners and political leaders. She said she cannot embrace the idea that the leaders of the first rebellion committed suicide.

With a lot to think about, we headed from the plantation back down to the shore and walked back the way we came. Barbara looks like she’s wearing a flag but that’s actually a life preserver. She wouldn’t ride in the dinghy without it.

Our dinghy had floated off the beach but the weight that served as anchor held it, and we climbed in and headed back to Easy Wind, where we lazied away the rest of the afternoon and drifted into another beautiful sunset.

We cooked pasta, tomatoes and chickpeas in the small galley and listened to jazz. When we wandered up on deck to look at the sky, we beamed our flashlight down and found a couple of Barracuda, with golden eyes, circling near our dinghy.

Wednesday’s dawn was a beautiful promise.

We planned to head around Mary Point to Maho Bay or Francis Bay that morning. But before we continued on, our fuel gauge told us we needed more diesel. The closest fuel docks were in Soper’s Hole, a busy port at the west end of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands.

Technically we’d have to clear BVI customs and immigration before we fueled up. “This is not where ‘BVI Love’ is found in abundance,” warned our cruising guide. The process was a time-consuming hassle. We would have to use the Sailclear app, deal with several officials, pay port charges, and might get backed up behind one of the inter-island ferries.

We decided to see how things went. So we crossed the international border and entered Soper’s Hole between Little Thatch Island and Frenchman’s Cay.

We moored Easy Wind as far from the customs offices as possible and got in the dinghy to find a fuel dock.

We quickly found the Voyage Landing T-dock with a diesel pump at the end. We dinghied back to the mooring and brought Easy Wind over. A few minutes later we were topped up.

Barbara went shopping to the Riteway Harbour Market, bought a couple of steaks, some friend and fresh bread for breakfast.

Our goal when we crossed back into U.S.V.I waters was either a spacious and well-protected mooring ground called Francis Bay, or Maho Bay directly across the water. Maho Bay boasts a beautiful beach, but there wasn’t a sailboat in sight there.

The cruising told us that the winter currents made it inhospitable for mooring. So we went back across the bay and this time picked up a mooring without drama. A sailor on the boat across the way nodded in approval.

A swim was our reward and Barbara narrated, comparing Nick to the Barracuda we saw the previous evening.

We felt the glow of our successful mooring capture and lolled around the deck.

We watched bigger boats come into the protected bay including a Windjammer that made a brief appearance.

The spectacular sunset that evening painted the sky with color as we had drinks on the deck.

We ate our steak dinner below in the saloon, and then went up on deck to watch the spectacular show in the night sky.

Thursday morning, the sun cast a spotlight on Francis Bay and we enjoyed the calm before we had to head back to Caneel Bay.

There was very little wind, so we motored past Maho Bay to get a closer look.

Then we steered the boat into deeper water and turned toward Caneel Bay. Once there we picked up a mooring without incident and dinghied in to Cruz Bay to return our rented swim flippers. Nick waited with the dinghy while Barbara went in search of the National Park Service to pay the $104 in fees for our four nights on its moorings.

Back on Easy Wind, we left Caneel Bay behind and steered west to Pillsbury Sound and then south. We left Dog Island and its knife-sharp Dog Rocks to starboard.

Safely past them, we turned west toward Charlotte Amalie. We took turns at the helm for the two-hour trip.

It was starting to drizzle when we entered Charlotte Amalie harbor.

Waypoints wanted us to pick up a mooring off their dock for the night. We snagged a mooring line on the first try, but it didn’t have an obvious eye to thread a line through. Barbara held on to the mooring ball with the hook while Nick try to find a way to thread the line. And then the mooring pulled away taking the boat hook with it. We groaned and Barbara called the two emergency numbers we had. On the second call her phone died.

Out of nowhere Larry, one of the Waypoints staff, circled Easy Wind in his dinghy. “I was on my way home and got your call,” he said. We gave him our line and he tied it to a mooring ball and then took off after telling us we could dinghy to the dock to shower, and have dinner and whatever. Of course it would be pitch dark when we were doing that.

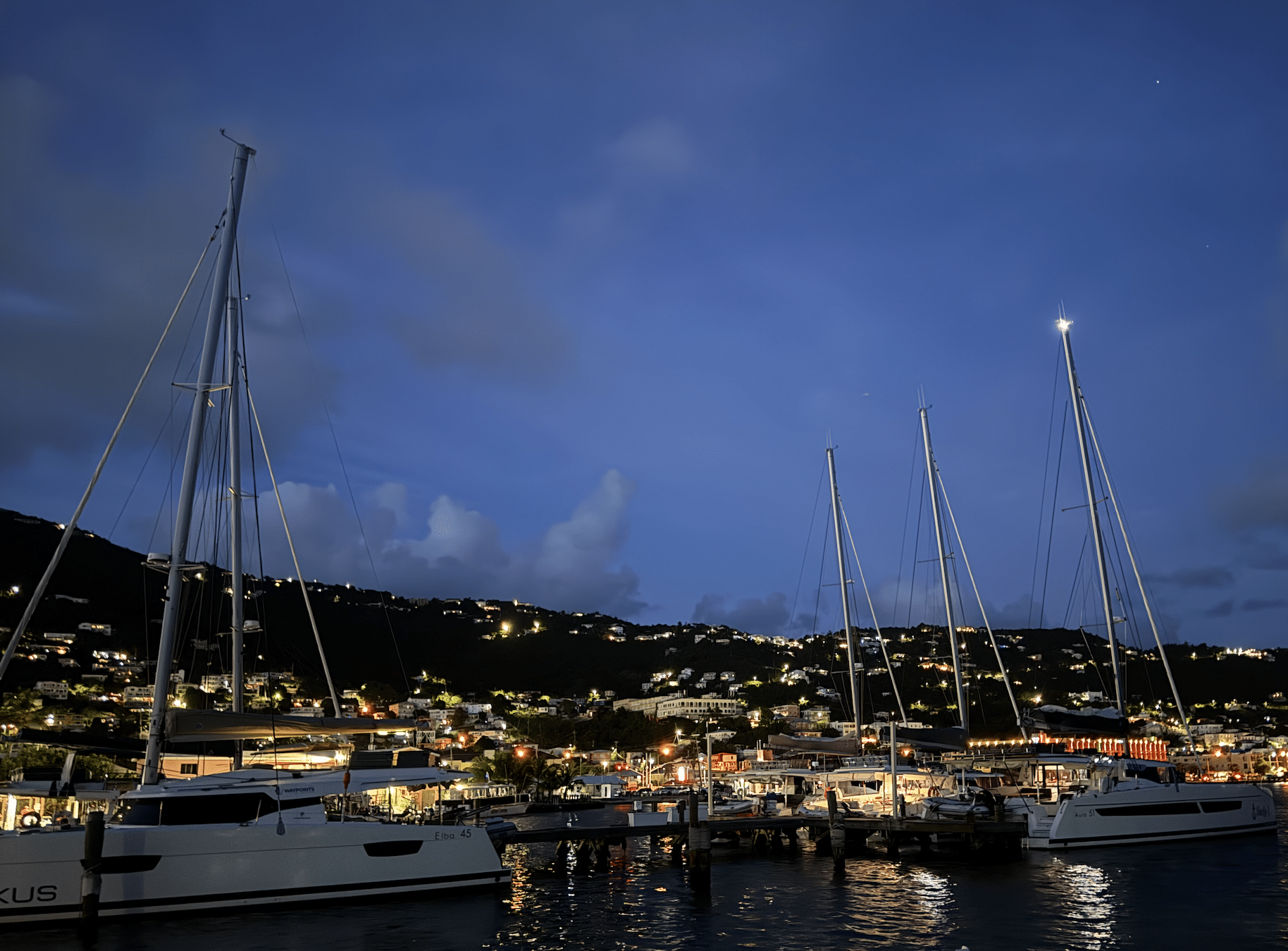

This little harbor was a busy place with air taxis and ferries coming and going.

And we felt uncomfortable. But again, out of nowhere another dinghy arrived. Andrew Davis, the base manager, and his girlfriend Ellie, approached Easy Wind. “Give us the line for your dinghy,” Andrew called. And we did. They sped off with the dinghy and returned to bring our boat into a slip at the dock. “This way you’ll be more comfortable, ” he said. He took the helm and maneuvered Easy Wind stern-first into a nice slip at the end of a dock, secured the lines, and hooked up shore power. “It’s my day off. But when I got your call, we came right over to help,” he said. We felt so grateful and relieved.

After showering and freshening up in the restrooms on the dock, we watched the lights of Charlotte Amalie come on before heading to dinner. We had booked in advance at a harborside restaurant called Cuvée.

After a week of steak on the boat, we craved fish and ordered tuna.

Chef Dougie Daniel came out to greet the guests and he and Nick connected.

The next day, we enjoyed our last morning on Easy Wind and packed up our things ready to say goodbye to the beautiful Virgin Islands. Justin, a Waypoints manager, came aboard to find out what worked, what didn’t and found the boat in good shape.

Bazil, the Ricci’s taxi service driver who’d picked us up when we arrived, was back to take us to the airport. His radio was tuned to a replay of Jason Carter’s eulogy for his grandfather Jimmy, who ‘d been buried the previous day. We admired Jimmy Carter. Nick had worked in his presidential campaign doing advance for Rosalynn and it was lovely to listen to the tribute.

But our minds were on what we had accomplished. We’d proved to ourselves that in good weather we could still manage a sailboat as a couple. That felt good, but we also learned that in the future we should sail with a captain.

A few hours later, sweaters and coats on over our T-shirts and socks on our feet for the first time in a week, we were back home in New York.