by Barbara Nevins Taylor

Our mom called Mother’s Day a greeting card holiday. Yet the mushy romantic side of her wanted a card, a gift and a wonderful lunch. I wish we had a chance to have one of those lunches again.

I took my mom to lunch the day before she died and neither of us thought that it would be our last. I thought I’d still be driving her to lunch when I was 102, and I have to say that at the moment the idea flashed in my mind it didn’t make me happy.

We had recently celebrated her 95th birthday and while she was getting wobbly, she seemed okay. She suffered from dementia.

She knew me and my sister, her sons-in-law, her brother and his wife, her best friend from childhood, who visited often, and the assisted living staff at Atria Tanglewood in Lynbrook, Long Island, her home in her last years.

She liked going to lunch. “Let’s go to our place,” she’d say. She had a crush on Bill Tsemplis, the owner of the Valbrook Diner, and flirted with him.

He flirted back. She also liked the people who waited on us. Most of the time, we had fun at these lunches and laughed a lot. She carried on a conversation up to a point.

She often ordered pancakes and drenched them in syrup. One day she saw someone eating a mound of french fries and ordered them too. When the server brought the pancakes and the french fries. She shook her head, laughed and asked, “Who orders french fries with pancakes?”

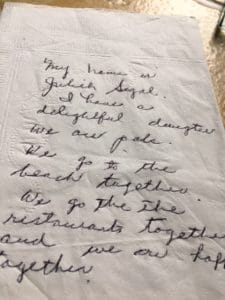

Because she refused to wear a hearing aide, I had to sit across from her so that she could read my lips. “Speak up. Stop mumbling,” she often said. At that point I resorted to writing notes on napkins.

Many of these written conversations involved her family. “How are the folks?” she’d ask. She thought her mother and father were still alive. A few years earlier, when she was still using the telephone, she discovered a Sarah Robin, her mother’s name, in the phone book and called this woman frequently.

After the first time, she called me crying. “Why won’t my mother talk to me?” she said. “She hung up on me.” I was with my husband in South Carolina where he was giving a talk, and I felt like laughing and crying at the same time. All I could think to say was, “Mom, that’s not Grandma. It’s someone with the same name. Grandma wouldn’t hang up on you.”

Then she demanded, “Well, where is she?” I knew this was tricky territory but I went there anyway: “Mom, she died a long time ago.”

“That’s not true,” she said indignantly and went rolling down the rabbit hole. “Why did my mother hang up on me?” she asked again and again. When I didn’t give her the right answer, she called my sister. Then she called her brother.

Our mom was persistent and this went on for a bit until the woman changed her number.

At our lunches, the conversation turned frequently to her age. “I can’t be that old,” she would say. “Do the numbers,” I suggested. She had been a teacher and a bookkeeper before that. She knew her math. “What year were you born?” I asked. She’d write it down on the napkin and she says, “What year is it?” I’d tell her. She’d do the subtraction and say, “Impossible. Impossible.”

“How old are you?” she challenged me. “I never tell my age,” I would say. She laughed and said, “That’s ridiculous. I’m your mother.”

She died peacefully in her sleep. It was her time and all of that. But I do miss her and those lunches and wish we had a chance to it again. I know my sister Hope feels exactly the same way.

Read Nick Taylor’s story about an orphan and his mother