by Nick Taylor

I walked by a fortune teller on the street the other afternoon. She was young and beautiful, dark hair cascading across her shoulders, dark eyes smiling at passers-by who might want their fortunes told. I don’t what lies ahead in the wake of my prostatectomy, but I smiled back at her and said, “My future is shorter than my past, but I’m looking forward to it.”

Writers have had a lot to say about the prostate over the years. Anatole Broyard of The New York Times Book Review learned in August 1989 that he had prostate cancer. He died of it fourteen months later, when he was seventy, but in the meantime wrote Intoxicated by My Illness. He said it woke him up: “Illness is primarily a drama, and it should be possible to enjoy it as well as to suffer it.”

Scottish urologist Gavin Francis recently reviewed two books about the troubled prostate in the New York Review of Books. One was the writer’s account of his diagnosis, surgery and convalescence as the covid pandemic was beginning, the other a look at how culture has approached the prostate since medicine identified the troublesome gland in the sixteenth century. Francis pitched in that his patients treat their prostate problems with “an odd mixture of anxiety and jokey bravado; they find it easier to make wisecracks about the prostate than to confess their fear of disease.”

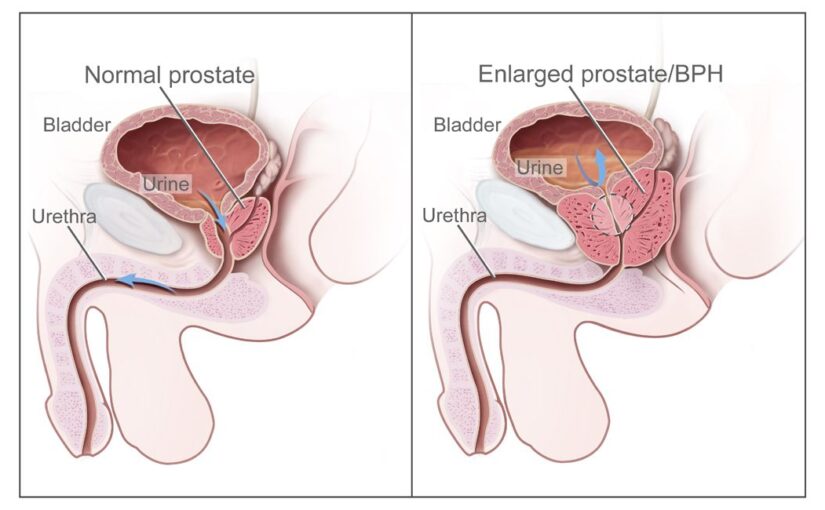

Most writing on the subject undoubtedly has escaped young, healthy men. Why give a thought to a walnut-sized gland that sits at the base of your bladder if it’s not malfunctioning?

That is to say, if you can easily summon an erection and you don’t leak pee inside your pants. But those two functions have a lot to do with how we men think about ourselves. That little fellow is responsible for a big part of our identity. I remember a Top 40 song from the 1960s titled, “You Don’t Know What You’ve Got (Until You Lose It).” It was about teenage love, but it could have been about the prostate.

When you’re older, though, you have to rethink who you are in any case. A sore shoulder hampers that once-effortless forehand. Touchy knees hobble your easy running stride. The sounds you make rising from a chair are heard across the room. A troubled prostate is a part of that continuum. As Anatole Broyard discovered, it helps to think of all this, painful though it may be, as an adventure.

When I came home from the hospital I carried a sheaf of post-operative instructions. Some addressed short-term problems like dealing with my catheter. As news anchors say before their technicians cue up scenes of violence, “Some of these images may be disturbing.” And while readers may find my adventures with my catheter a fascinating voyage of discovery, I’ll leave them to the imagination. It’s enough to say that it’s a device that requires some care in handling.

The catheter wasn’t all I had to deal with. The surgical incisions across my belly were glued shut, but still painful. I couldn’t sit up to get out of bed; I had to roll out onto my hands and knees and then stand up. I filled an oxycodone prescription that I carried from the hospital, but one of those was enough before I moved on to Tylenol. On another recuperative front, passing gas halfway through that first week meant I could now expand my post-surgical diet of clear liquids to include soft solid foods and eventually ordinary meals. I’d soon be able to enjoy eating once again.

I was told to expect a swollen scrotum. “This is common and should not alarm you,” the post-surgical information sheet assured me. The lack of alarm lasted just one sentence. The one after that said, “Your scrotum may become as big as an orange or grapefruit.” Sure enough, one morning I found that my penis and an inch of catheter had disappeared within the folds of my scrotum grown to the size of a small grapefruit. With wrinkles. It looked more like an ugli fruit, which is a good description. The endlessly helpful information sheet told me I could roll up a towel or washcloth to elevate and support that big boy during the week or two that this might last.

A week after my surgery I strapped on my catheter’s leg bag, tucked my large scrotum into my underwear, put on some clothes, and Barbara and I took a car to 221 East 41st Street to have the catheter removed. I was looking forward to it, but I didn’t think I was going to have fun. As it turned out, I practically laughed the catheter out. This was the doing of a team of young nurses named Danielle and Elinor, who had had enough experience with catheters to see the humor in them if the patient saw it too.

What happens during catheter removal is that you drink some salty water and then see if you can pee it out through the catheter into a plastic receptacle. This is what I did under Elinor’s supervision. I struggled at first. It wouldn’t come out. Then, in adjoining room beyond a curtain, Danielle triggered the universal urination impulse; she turned on a water faucet. It was so obvious I broke out laughing. And it worked. That meant my bladder functioned. Moments later, Elinor had somehow deflated the balloon that held the catheter inside my bladder and pulled the contraption out.

Moments later, I was wearing a pair of Depends under my sweat pants and Barbara and I listened as Danielle explained what was going to happen next. “Bladder Training” headed the list. You need this because without a prostate you’re also missing one of the things a man needs in order not to have to wear Depends. That’s the involuntary or internal sphincter that pinches your urethra, which carries urine from your bladder to the tip of your penis. With it, you don’t have to think about not peeing in your pants. Without it is another story. Thus the bladder training.

There’s another sphincter, the voluntary or external sphincter, farther down the urethra toward the penis. We’ve all clenched it in the middle of a pee. Now the bladder training means you’ve got to wake it up to step in for the one that’s missing. How do you do that? Kegel exercises. You clench it up, regularly and repeatedly and more frequently as time goes on. You graduate from Depends to pads inside your shorts (snug shorts; no boxers, please) until after a few months you might be dry again.

In the meantime, you try to plan ahead. Seconds ahead. You have to anticipate things you didn’t much think about before, like coughing, sneezing, blowing your nose, and even clearing your throat. Because if you don’t think about it . . .

I was a weekend into this journey when big news arrived. MyChart told me on February 14 that I had new test results to look at. It was the pathology report of my dismembered prostate. Which, for the record, had weighed 72.4 grams and measured 6.2 by 4.5 by 3.9 centimeters. Bigger than a walnut, then. The cancer had registered 4+5=9 on the Gleason scale, a rating that determines how aggressive the cancer is. Ten is as high as it gets. But while my cancer was aggressive, it involved only 2 percent of prostate tissue. “Tumor is confined to prostate,” said the report. I would have tried to turn cartwheels, but my bladder training suggested that would be a bad idea.

With that I turned to the next compelling signpost along my journey of recovery: “Post-Operative Sexual Rehabilitation.”

Like most men, since puberty my hormones dictated my behavior in certain situations, giving rise to a good deal of pleasure and some misadventures. And like most men of a certain age, my river of testosterone had slowed to a mere tributary even before my surgery. My hormones had to be coaxed out of retirement and persuaded to participate. They could still pitch in enthusiastically, but they had to be reminded of old times. The absence of my prostate did not improve things. I came home from the hospital with a prescription for 5 milligram tadalafil tablets — that’s generic Cialis — that I take every day. The chapter advises you not to expect to be the stud you remember for six months to two years, however.

You can resort to more elaborate measures if you choose. You can inject your penis with something that increases blood flow. You can stick it in a tube from which the air is pumped out, which also increases blood flow. Or there are penile implants.

Meanwhile, four months post-surgery as I write this, I’m still struggling to reacquire the rhythms of what I remember as a “normal” life. The COVID pandemic hasn’t helped. Nobody’s life is normal, after all. Lives aren’t normal in Ukraine, or among American women who might get pregnant, or in wildfire-prone states, or in schools or churches or stores or any other place where disturbed people with guns decide there are other people they just have to kill.

Meanwhile an explanation of benefits from United Healthcare, where I have my Medicare supplemental insurance, arrived in the mail. It told me Medicare and United Healthcare paid almost $12,000 combined for my prostate surgery and the accompanying procedures. A lower line told me I was fortunate that NYU and Dr. Taneja accepted Medicare assignment. The actual amount charged was $148,119.27. So outside a privileged life like mine, even the hope of a return to normal would come at a cost much greater than most people can afford.

And I am doing some of the things I used to do. I’m playing tennis, doing yoga sessions with Barbara, going to the gym, walking and riding my bike, doing the Saturday morning shopping at the farmers market at Union Square. Some other things I once thought were part of what defined me I can do with less of. But other definition points remain.

I still have things I’m curious about. I still have things I want to write. I still have friends and family I cherish and want to spend more time with. I still want to witness the beauty of humanity and nature that lies before us everywhere. There are places in the world Barbara and I still want to see together, lots of places. I still have love and kindness to give and conversations to hold and flowers to smell. I still can show every day the gratitude I feel for the life I’ve had and the life that’s yet to come. As I told the fortune teller, my future is shorter than my past, but I’m looking forward to it.

It is difficult to read of your journey, which many men may experience if they live long enough. But the dread that accompanies the reading is lessened by the discussion and in the positive way you have dealt with adversity. One is reminded that no matter what happens to us, we have the choice of how to frame it in our minds. Thanks for sharing your experience l.

Thanks, Alec. Yes, attitude! And I got my post-op PSA results back, showing virtually zero as to be expected.