by Nick Taylor

Johnny Mills sat in the darkened front room of his small frame house outside of Sylva, North Carolina. A bandage covered a side of his face where a rash from shingles made him wince with pain. We asked if he wanted us to come back another time, but he said, “No. Work on those roads rescued me and my family and I might as well talk about it now.” It was November 2002, and we were researching American-Made, my history of the Works Progress Administration. As he talked the clock rolled back over sixty years.

Sylva and Jackson County, in the western North Carolina mountains, were firmly Democratic in 1938. FDR’s New Deal was attacking the Depression and his jobs program, the Works Progress Administration, was easing unemployment that reached 25 percent before he took office five years earlier. Mills was a Republican and he feared WPA jobs weren’t meant for him. But his wife Shirley was due to deliver their first child and he needed money for a doctor.

Mills didn’t call it infrastructure. People barely used the word back then. But his experience shows that government projects can fill public needs, help individuals, and bridge ideological gaps all at the same time. It’s a reminder that the divisions that time and again rip Americans apart start with politicians, not the people.

When Mills went to apply, he found to his surprise that politics didn’t dictate his success. The county supervisor was a Democrat, but he approved Mills’ application. “He was a good fellow,” Mills said. “He’d lived up in the mountains and he knew how it was. He wanted to be fair.”

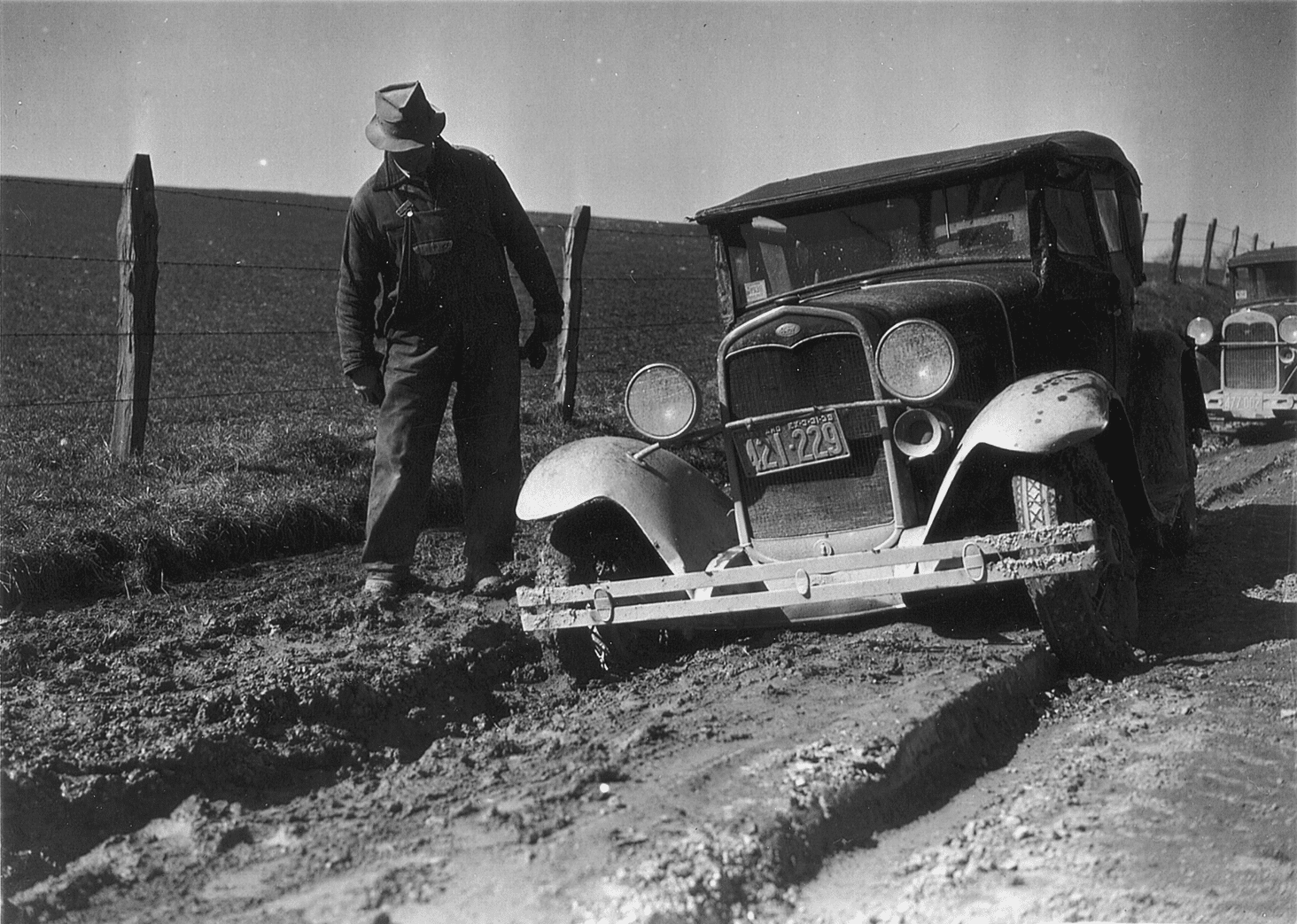

Mills went to work on a WPA road construction crew. Rural North Carolina in the 1930s faced yawning infrastructure shortfalls. Local and county roads were rarely paved, or even graveled. Jackson County, for example, had just half a mile of paving in its 351 miles of road that weren’t state or federal. Commerce suffered. Farmers sank into mud holes trying to drive their crops to town. Impassible roads meant market shelves stood empty. That’s why farm-to-market roads were a major thrust of the WPA’s rural road construction in North Carolina and throughout the country.

Johnny Mills began his day around four in the morning, carrying a lantern to the barn to milk his single cow. Then after Shirley cooked breakfast and packed his lunch, he walked a mile to a main road where a state truck picked him up for the drive to the day’s job site. The crew worked hard. They dug road paths along hillsides, cleared woods, cleaned ditches, and crushed rock into gravel. They made $44 a month. Mills used some of his money to pay the doctor who attended Shirley when she delivered their daughter Patricia at home in April 1938.

The experience silenced for him what was, even then, a popular Republican talking point. Conservatives called the New Deal socialist. They said the WPA put people into make-work jobs of little value, or boondoggles as they were called. Mills disagreed: “When people talked about [us] leaning on the shovel, well, we did a whole lot of work. And a whole lot of hard work. There was some that thought you was on relief, but I know I was working for money when I was doing that. It wasn’t no different than no other job. You earned the money. It was for the needy people Good people, they can’t always help hard times, tough luck. I always figured I tried to make a living for my family. And it was a help to us.”

Today’s North Carolina politicians in Washington are now solidly Republican. But they might heed this echo from the past. The New Deal work of the WPA and other job programs brought America’s infrastructure from the 19th century into the 20th. Today, two decades after it began, we need to move into the 21st. Polls tell us most Americans want transportation, technology, and human infrastructure to match today’s real needs. And they want the jobs that will result. Johnny Mills went bipartisan in 1938.

Representative Madison Cawthorne, who represents Sylva and western North Carolina, should rethink his vote earlier this year, when he sided with other House Republicans against funding programs that could improve the communities he represents. Senators Richard Burr, Tom Tillis and Republicans in other states also should consider putting partisan ideology behind. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell won’t sink into potholed roads or be unable to sign on to the internet in the states that won’t get funds. Ordinary Americans will have those problems, when instead they could be driving on smooth roads, crossing new bridges, and enjoying rural broadband access that connects them to the world.