by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

The drive from Bosa to Alghero ranks among the most spectacular sea views Sardinia offers. We swept around a curve, the hills fell away, and the blue Mediterranean practically hit us in the face. Every roadside pull-off beckoned us to stop for yet another cell phone shot of green and flowered cliffs dropping to the sea.

We stopped at one pull-off and joined a camper van, whose occupants had had the same idea.

We were taking pictures when Horst and Ilana, a German couple from Bavaria, walked up and introduced themselves. They had driven through Austria and northern Italy to Livorno, where they took an overnight ferry to Olbia on Sardinia’s northeast coast.

That put them in the middle of the fabled Costa Smeralda (Emerald Coast). But the fables were perhaps overblown. It’s “like Disneyland,” Horst said. “Beautiful but plastic. George Clooney’s there,” he laughed.

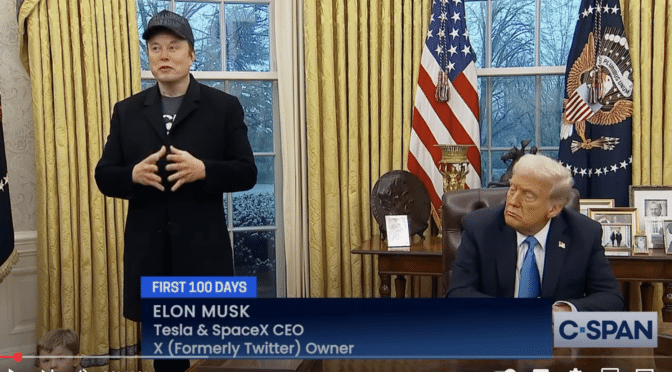

Ever since the Aga Khan and his friends opened a yacht club at Porto Cervo on the Costa Smeralda in 1967, the area has attracted the international sailing crowd, celebrities, the rich and those who want to be, the beautiful and their admirers. And since Soviet communism gave way to Russia’s state-sanctioned oligarchy in the 1990s, the oligarchs steamed up in their mega-yachts to join the party.

We’re both sailors, but none of that had much appeal for us. We had already decided to bypass that part of Sardinia, and Horst confirmed our judgment. We were hoping to find Alghero more attractive.

From the hillside, we could see the small city across the water and felt eager for a new part of our adventure. Alghero has a long history as a commercial and military hub and we read that it retained a strong Spanish flavor.

But the inventive Bronze-age Nuragi settled here long before the Spanish invasion.

And in their time, they used the strategic location to trade metals and pottery with the Phoenicians and others who traveled this part of the Mediterranean

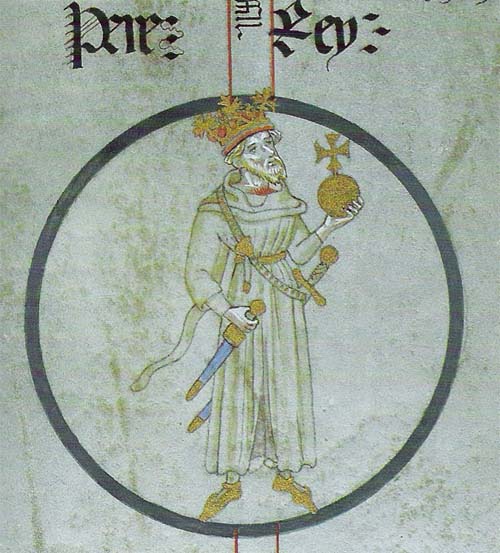

By the 12th century, Alghero became a fortress town ruled by the Dorias, a Genoese family. The walls and defensive catapults they built did them no good, though, and they lost control to a family from Pisa. The Pisans had a problem with the Vatican, and in 1297 Pope Boniface VIII handed over Alghero and Sardinia to King James II of Aragon.

It was what we’d call today a virtual handover. It took almost thirty years for Peter, King James’s son and successor, to muster the ships and the navy to invade and actually take over in 1323.

War then raged between local family dynasties and the Aragonese Spanish for nearly 100 years before the Spanish gained a firm hold on Sardinia. But in Alghero, King Peter IV expelled locals and replaced them with Spanish prisoners, prostitutes — and we hate to add this to the list, but history says it’s so — Jewish people.

Hapsburg kings ruled for more than 200 years from 1516 to 1720, northern Italy’s House of Savoy held sway until Italy unified in 1861, and through it all the Catalan influence remained in northwest Sardinia. Today, an estimated 15 percent of Alghero’s 44,000 residents speak a form of Catalan.

We were looking forward to exploring this mash-up of Mediterranean cultures when we drove into town.

Barbara had booked us into a B&B in the old part of the city near the water. It was in a pedestrian zone and we unloaded at a small plaza nearby before going in search of one of those blue-lined parking spaces.

At Palau de Rosa, we rang the bell and the door opened to reveal a man sitting on the steep steps. He introduced himself as the husband of Giovanna. She had taken his family home and turned it into a B&B offering three rooms.

He took us to us to the small, clean, charmingly decorated room that was dark despite a window on a narrow street. He also showed us the tiny — one table with six chairs — breakfast room that looked out on the street in front.

Then he bowed out hurriedly saying there was someplace he had to be.

Finding a parking spot turned into a chore. By the time we got the car safely situated, decent restaurants weren’t serving lunch and we ended up at place under the umbrellas across from the B&B.

Finding a parking spot turned into a chore. By the time we got the car safely situated, decent restaurants weren’t serving lunch and we ended up at place under the umbrellas across from the B&B.

Barbara ordered calamari fritti, which tasted like frozen food barely cooked. It went uneaten. Nick’s food seemed slightly better. When the bill came for a less than mediocre meal it added a ten euro cover charge. I asked the waiter what the cover covered. “Things like cooking and washing dishes. Like Rome,” he said.

Italian restaurants don’t expect tipping unless you’re really happy with the service and then it’s mostly a matter of rounding up. Many of them add a cover of a few euros to the bill, but ten seemed excessive, especially in this place.

Alghero just didn’t speak to us, and we’d only just arrived. We had planned to stay two days. At the suggestion of a fellow traveler we’d met in Cagliari, we booked a day sail on the Andrea Jensen, an old Danish gaff-rigged ketch.

It offered a day of swimming and snorkeling and a glimpse, from the water, of Neptune’s Grotto, a stalactite-hung marine cave .

Crowded tour boats could take you there, too, and for a lot less than the 150 euros apiece we’d be paying, but this seemed better.

That would make the second day in Alghero more of an adventure. But in the meantime, we got back in the car and drove out to the northwest past Fertilia to Porto Conte.

We found a pull-off where a dock jutted into the water and some rocks proved comfortable enough to sit on and get our feet wet. On the way back we stopped at a small beach and took a walk along the shore.

Our first impression of Alghero got worse when — our fault — we failed to book a restaurant for dinner in advance. We stopped to see if Al 43 di via Doria could fit us in. They could, but not until 9:45.

So we walked the old city walls and mellowed with the twilight.

Restaurant prices along the wall seemed high for what their menus offered and we were glad that we decided to wait for something more special.

So we sauntered.and found ancient catapults used long ago to try to repel invaders.

Twilight gave way to sunset and restored our good moods.

As we were taking photos under the moon,

Barbara’s phone rang. It was Rachel, from the Andrea Jensen. She said she had to cancel our boat trip. No one else had booked and they couldn’t afford to take just us. Time for Plan B and moving on from Alghero.

But first, the blazingly unique and utterly charming restaurant Barbara found.

We arrived back at Al 43 di via Doria a few minutes early to treat ourselves to prosecco while we waited for a table.

Whoever had designed the dining rooms had a fine eye — lamps and chandeliers, lush draperies, ornate mirrors, a silver bull’s head, free-standing cabinets under the curved arches of the rooms. It was quirky, striking and inviting.

So were the women who ran the place, the chef and mastermind being Luisa Gagliotta. They chose different outfits for each evening. This night it was short black organza dresses. The menu options ranged from vegetarian to gourmet burgers, but we stuck with seafood and weren’t sorry.

The crudo starter was a long time coming but when it reached the table we saw why: the kitchen had produced a work of art. And the meal continued with beautifully prepared, delicious food.

Back in our room at Palau de Rosa after midnight. Barbara went online and booked us into Su Gologone, a resort that promised mountain luxury near Oliena on the way to Sardinia’s east coast.

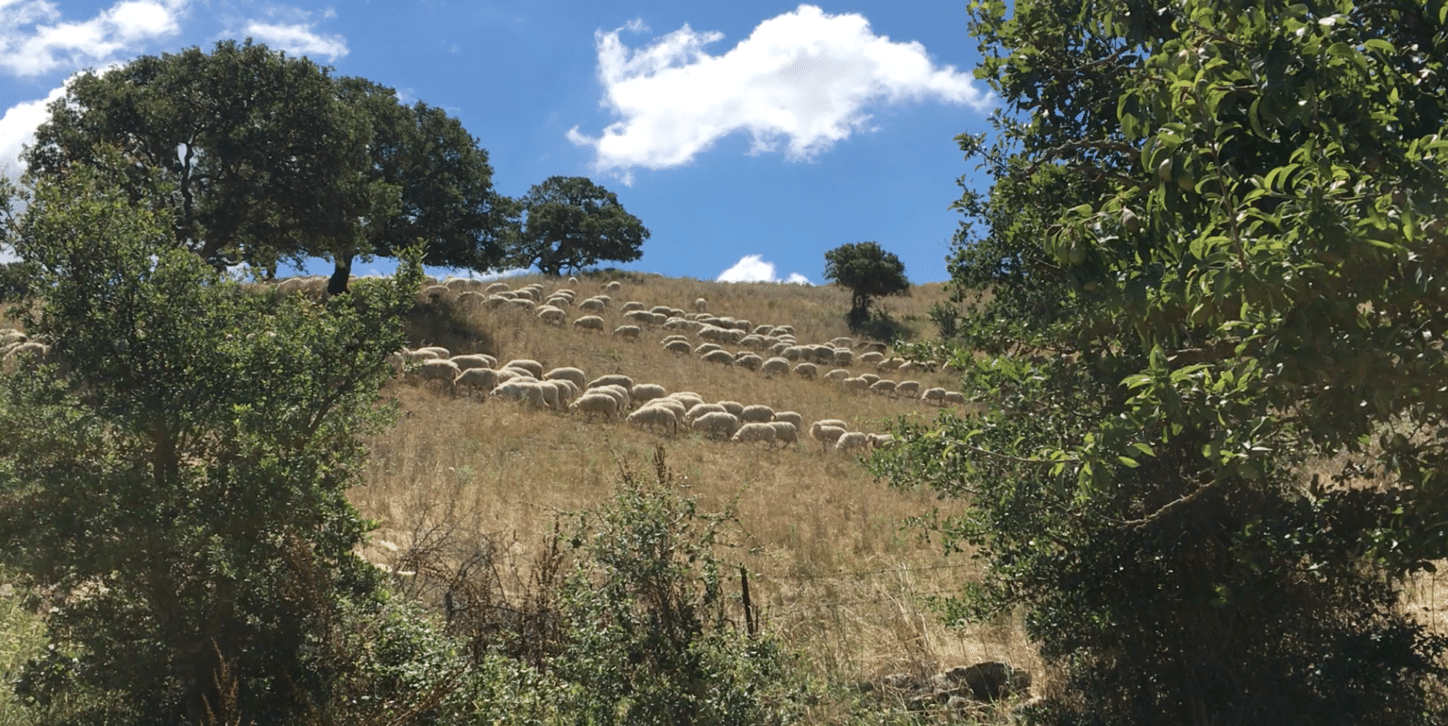

Our route that Tuesday took us through farm and sheep country. Neat, tightly-rolled hay bales lay strewn across cut fields.

At one point we heard this strange sound even through rolled-up car windows.

We looked to our right and saw hundreds of sheep apparently herding themselves. We didn’t see dogs, or herders, just the sheep moving in an eerie flow toward some unseen point.

The road took us higher in the mountains and the first thing that struck us as we neared Nuoro and the turn south to Oliena was the slab of sheer rock mountain that walled off the horizon to the east.

Mount Corrasi is the highest peak of the limestone massif called the Supramonte that attracts climbers and hikers to a part of Sardinia once known as a hotbed of banditry.

At Oliena we skirted Corrasi’s north end and then the Supramonte’s rock walls rose on our right.

A few miles east we found the turnoff to Su Gologone and drove into the resort.

“What a difference a day makes!” Barbara wrote in her notebook when we’d looked the place over. What started as a country restaurant in 1967 has transformed into a lavish “experience hotel,” as the resort’s website puts it.

Our second-floor room

gave onto a covered terrace with set-in upholstered couches

bracketing a huge square bathtub, intended for soaking after a long mountain hike or romance.

Moments after checking in, we were seated at Su Gologone’s terrace restaurant looking out over the swimming pool onto a long vista of rolling hills and olive groves.

In the countryside and the Barbagia region of Sardinia, roasted lamb, pig and goat supplant fish on the menu.

We quickly and happily learned that at Su Gologonne they spit roast the meat and serve seasonal vegetables from their farm and garden. And when we sat down we found a thin pane carasau, a salty flatbread prepared by the hotel bakers on our table. Its name translates as “sheet music bread.”

Nick ordered lamb ribs, Barbara a pasta with tomatoes and eggplant and a zucchini salad with lemon.

The mountains that loomed west of us were part of the Gennargentu National Park.

Just to cover all the bases, Sardinia put the Bay of Orosei to the east into the same park, so whether you hike, bike, climb, swim, dive, go spelunking in caves or practically any recreation in between, you can find it all within a relatively few miles.

But for hikers and trekkers, the Supramonte and the Gennargentu mountains are a wealth of opportunity. Thirty-three trails cover terrain that will take you from canyons to peaks with spellbinding views.

That’s why most of our fellow guests at Su Gologone, whom we had started to meet at the swimming pool, had booked for several days, and barely managed to conceal their pity when we told them we were staying just one night.

But we’d lucked out. That night’s special meal, offered only on Tuesdays, starred Sardinia’s inland specialties of roast suckling pig and roast lamb. Dark had fallen when we followed a candlelit path to the courtyard where we and our fellow diners would enjoy this feast.

Outside Matteo, in a slim black suit, welcomed the guests with almond sweets and Ororosa, a sparkling rose from the local winery Cantina Oliena.

The roasting chef and servers watched from the sidelines, behind them a fire pit where the roasted pig and lamb were resting.

A table in the middle of the courtyard groaned with a dizzying array of locally-sourced starters: ham and sausage from Oliena, bacon with cardoons, coppa with artichokes, Oliena cheeses with vegetable and fruit jams and sauces, pan-fried fresh tomatoes and artichokes, empanadas, casadinas (ricotta and pecorino tarts) with artichokes. As we loaded our plates the multi-lingual Matteo gave us table assignments, grouped according to language.

We sat with a young New York couple, Jordan and Daniel, and an English couple, Dean and Liz. Jordan sells real estate and Daniel is the creative director at a hot ad agency; like us, they live in the Village. Liz, a fashion photographer, and Dean, an actor, were there to celebrate her fortieth birthday.

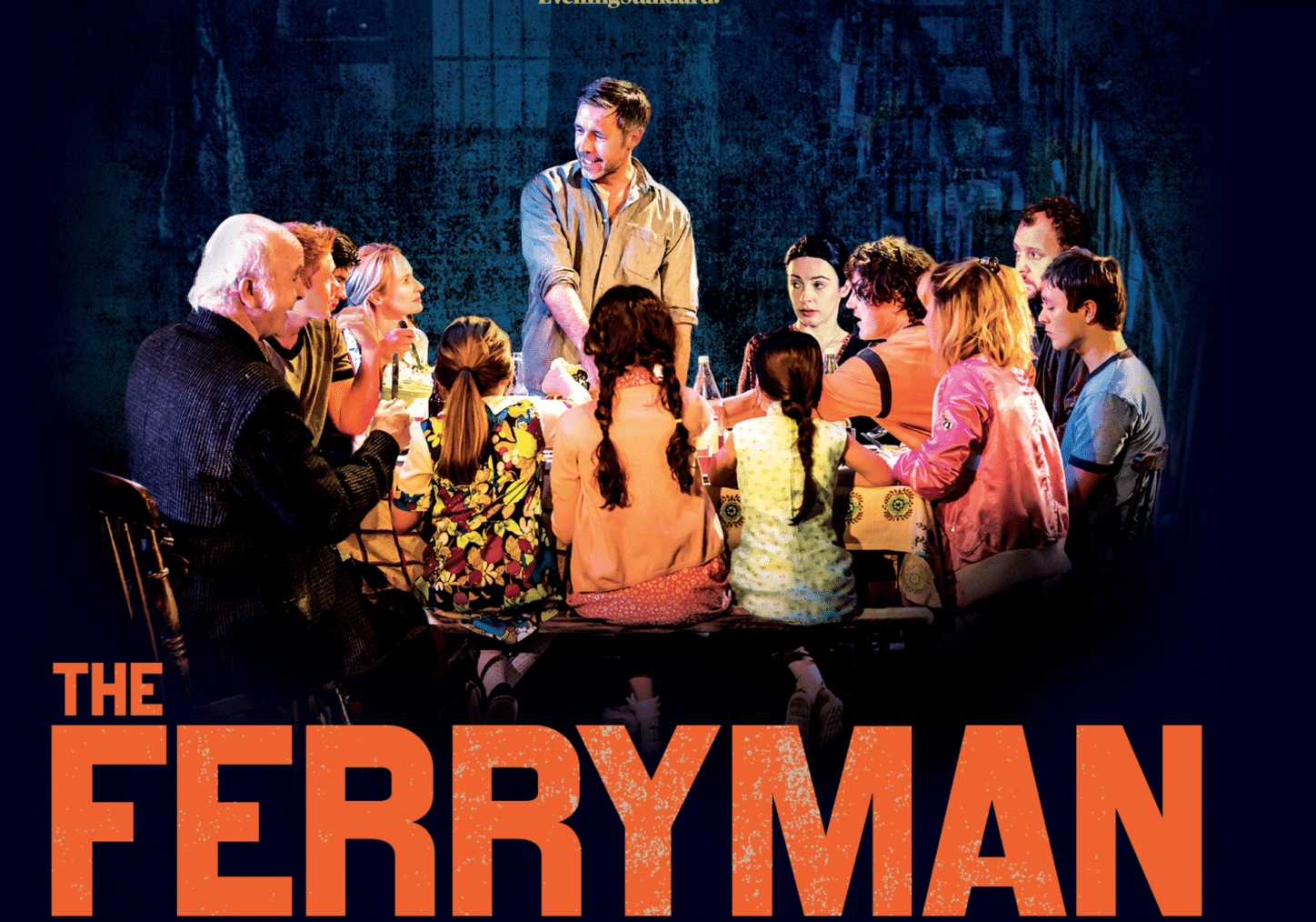

And they were New Yorkers-to-be, since Dean is a featured actor in “The Ferryman,” an IRA-era Irish play that’s conquered London’s West End with rave reviews and will open on Broadway in the fall.

Together we had a lot to talk about. It was the first time Donald Trump’s name had come up in conversation since we’d been in Sardinia. And everyone at the table worried about the direction of the United States, its policy of separating immigrant children from families at the border, Trump’s bromance with Putin, and the seething anger and resentment of Trump’s supporters.

And Dean, it turned out, sandwiched a career in dog training in among his acting gigs. Nick asked him if dogs could tell time. “Not really,” he said. “Unless you count the time since their last meal. They know when they’re hungry.” That led to a talk about animal intelligence, especially that of octopi. Dean said they were too smart to eat, so he’d stopped. We’re still thinking about that.

Meanwhile, the food (and wine) kept coming, so much that when a server offered raviolis in tomato sauce on top of the array of starters some of us shook her off to save room for the roast meats and the salads, fresh fruits and desserts to follow.

We all stumbled off to our rooms after a couple of hours and slept soundly. Tomorrow, while the others stayed on, we headed for the coast.

Read about the Nuragi at Barumini here.