by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

We wanted to explore the legends and history of the Peloponnese peninsula. When we looked at a map we realized some of the earliest and greatest stories of our western culture sprung from the rugged hills of the splayed-out foot of Greece south and west of Athens.

We admit to gaps in our education. So we hoped that by walking in ancient footsteps we’d get insight into the Greek imagination and understand more about the fragile underpinnings of the world and our democracy.

We drove out of the Avis lot at the Athens airport in a dark blue Opel wagon that was almost black.

An attendant gave us a map but said it wouldn’t help. Pointing, he said, “That ramp will put you on the freeway. Follow the signs to Corinth, then to Tripoli, and you’ll see signs to Nafplio.” Corinth, Tripoli, silly, but the names of the ancient cities had us dreaming.

Old maps and many travel sites render our destination’s name as Napflion. We couldn’t figure it out until we learned that it’s a so-called purist form of modern Greek called Katharevousa. But the country officially adopted Demotic Greek in 1976, and now the language drops the “n” at the end of neutral nouns and most Greeks write and say Nafplio.

Napflio or Napflion, we planned to make it our base for five days while we traveled the Peloponnese peninsula to visit the archeological sites and absorb the Homeric legends and the history.

Contests of sport and skill we now call the Olympic games started at ancient Olympia, near the peninsula’s west coast. Sparta groomed its warriors, in counterpoint to Athens’ intellectuals, toward the south. Ancient theaters still held the echoes of the western world’s first plays. Ruins of palaces held mysteries, and castles and forts marked the battlegrounds of centuries of war.

We sped west along the four-lane tollway averaging probably 110 kilometers per hour, skirting Athens to our south. We had international drivers licenses and were warned that we needed them if we were stopped by the police. Without them we’d face a 500 euro fine.

Google Maps told us we’d make the 167-kilometer trip in under two hours. We only slowed for the frequent toll booths, and as we handed euros to the toll-takers we began to understand why there wasn’t a lot of other traffic.

The tollways cost too much. We learned later, after talking to many Greeks, that they take back roads and the long way to avoid the tolls.

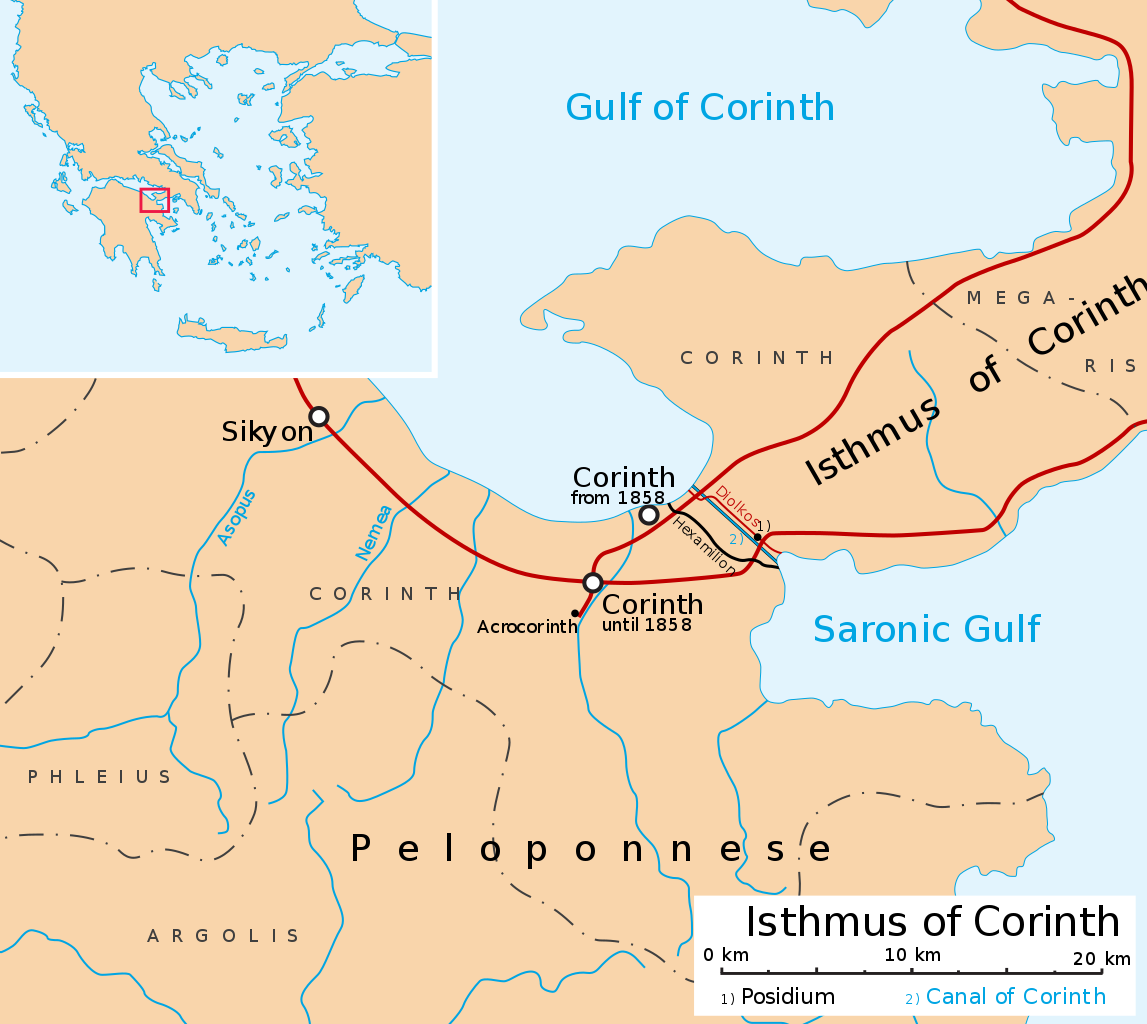

When we approached Corinth we saw signs to the Corinth Canal. The Peloponnesian peninsula joins the Greek mainland by a thin isthmus between the Gulf of Corinth on the west and the Saronic Gulf on the east.

Greek and Roman rulers talked about building a canal for centuries. Nero even broke ground in 67 A.D., digging up a basketful of earth with a pickaxe in what today would be a photo op. But not until the late 19th century did the engineering and financing align, and the four-mile canal opened in 1893.

We spotted it from the car as we crossed a short bridge, a straight blue line a long way down.

We parked and walked over to get a better look. A pencil-straight path carved through steep limestone walls plunged 300 feet to the water below. It’s a sea-level canal, so it has no locks. And it’s narrow, only 70 feet wide, which means small cruise ships and tourist boats can use it, but not most cargo vessels. Technically, that cut makes the Peloponnese an island instead of a peninsula.

We stopped at the adjacent roadside restaurant, ate some chicken souvlaki, a spinach pie and French fries and then headed south again toward Tripoli before signs and our GPS led us off the tollway and east to Nafplio.

The spectacular terrain was dramatically different from what we saw in the Athens area. Craggy tree-dotted mountains wrapped around the highway until Google Maps brought us through vineyards and farm roads as we wound toward the sea.

Nafplio lies on a northern tongue of the Argolic Gulf. It’s a town of some 14,000 people, with red-roofed buildings that rise from its harbor to a Venetian fortress that overlooks the water to the hills beyond.

It was the first capital of the new Greek state that emerged in 1823 after Greeks fought the Ottoman Empire for independence. We learned that the Greeks imported Otto, a Bavarian, to be their king.

We unloaded at the three-star Agamemnon Hotel, which we found on booking.com. Once we dropped our bags off, the desk clerk told us about free parking up the hill not far away.

The clean room was spare and functional. Its only drawback, in common with many Greek hotels, was that you couldn’t put toilet paper in the toilet. But we delighted in the view from our third-floor balcony overlooking Nafplio’s harbor, the Argolis Gulf, and Bourtzi Castle, a fort built in 1473 during Venetian rule.

We made ourselves comfortable and went out to look around. We walked up the hill from the Agamemnon and passed a blooming orange trumpet vine spilling over a stone wall. It added to the beauty we’d seen in Nafplio in just a few short minutes.

A left turn put us on a cobbled street that led into Syntagma Square. Pastel shaded neo-classical buildings bordered the marble-tiled square filled with cafés, small shops and a branch of the Bank of Greece.

Bicycles leaning against buildings with not a lock in sight caught Nick’s attention. This felt like his kind of place.

We found more to smile about on the main street of the old town filled with shops offering tourist stuff, clothes and sandals. Nick saw Socrates Sandals. He poked me. “Look at this. Imagine the Socratic dialogue he’d start with a question about feet: ‘What are bone spurs?'” he said, snapping pictures he was eager to share.

The foot theme continued when we spotted a shop with a couple of guys getting a pre-pedicure foot soak in a fish tank. No fish, though.

The rest of Nafplio rose up from sea level in winding streets and stone steps.

The climbs would take you from one level to another and ultimately to the heights of Palamidi Castle. We decided to leave the high ground for another day and went in search of a cocktail.

But first we stepped into the Church of Panagia. Modest on the outside, the church stunned us with its beautiful interior. Its name refers to the Virgin Mary, but it’s also the church of Nafplio’s patron saint, St. Anastasios.

The side door took us to a stretch of tavernas with outside tables. When we paused under a sign for the Alkioni Wine Bar, a charming young woman urged us to enjoy a glass of wine with them.

We didn’t need much coaxing and learned her name was Giorgianna. She sat us down, disappeared and reappeared with four bottles of Greek wine and four glasses for a tasting.

When we got to the last bottle she said, “Ah. Assyrtiko from Santorini. This one has a story. The bottles are placed in the sea for aging and that helps give the wine a distinct taste.”

Maybe it was the story, but the fourth wine was our choice.

We learned that Giorgianna had an immigrant’s story. Her mother had come to Greece from Romania in search of work. Two years later she sent for thirteen-year-old Giorgianna and her twin sister. The young women made lives for themselves in Napflio. Her sister was an artist and Giorgianna was learning about wines, trying to become an expert.

After our wine, we took a quick tour of the seaside tavernas looking for fresh fish. Some of the places displayed the day’s catch on ice in glass cases. At one, called Arapakos, the sidewalk spielmeister said it was “the best. If you believe me, I’ll see you later. If you don’t, have a good evening.”

We laughed and headed to the hotel for a nap.

When we back to Arapakos, Nick reminded the spielmeister we’d met earlier. “We believed you and we’re back for dinner,” he said.

As we lingered over the display of fish, the manager appeared by our sides. He introduced himself as Dimitri and said, “Come with me.” He whisked us past the indoor tables into a spotless kitchen and opened a drawer in the refrigerator showing fresh fish on ice. And then he opened another filled with mussels. “For whole fish, we have sea bass and snapper. Which would you like?” he asked.

We chose sea bass and he brought us back out to a table under an awning. We ordered Assyrtiko.

And as we enjoyed the wine, we realized the painting over the restaurant’s door showed the Bourtzi Castle with a chain across the harbor entrance and here was another story.

The Republic of Venice and Ottoman Turks battled for territory on land and sea from 1396 to 1718.

When the Venetians took strategically important Napflio in the 15th century, they built Bourtzi castle and put a chain across the harbor to keep the Ottomans and pirates out. In the 17th century, the Turks captured it and dropped large stones in the water to make sure no large ships could enter the harbor. Sounds a lot like an inspiration for George R. R. Martin’s “Game of Thrones” Battle of Blackwater Bay.

When Dimitri brought our fish we wondered about his excellent English. “Did you live in the U.S.?” Barbara asked.

“I’ve never been to the U.S. I worked for a multi-national company and everyone spoke English, even though it was German-based,” he said and then laughed, “I also learned from watching TV. I’m a big Star Trek fan and some people say I sound like a Canadian. I blame William Shatner.” It turned out Dimitri was one of the sons of Arapakos’ owner, and he and his brother Costa share the job of running the place.

The fish was delicious and we finished up with watermelon slices and headed back on the harbor promenade to the hotel.

Our second day took us into the heart of our mission in Greece. We headed to explore Mycenae, half an hour by car and 3,600 years away in history. Last summer in Sardinia, we’d learned that the Mycenaeans traded with Sardinia’s Nuraghi and learned bronze smelting from them. That led to bronze weapons and armor. But it wasn’t until businessman-archeologist Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations in 1876 that the wealth of Mycenae emerged from Homeric legend as stark reality.

As we traveled, we’d listened to Madeline Miller’s brilliant The Song of Achilles. It’s a prelude to and retelling of the Iliad from the view of Achilles and his companion Petroclus. Now, at the seat of Agamemnon’s kingdom, the audiobook brought a new dimension to the characters who made their home in these mountains. We bought tickets for 12 euros and headed for the hilltop citadel itself.

Our phones warned about a hot day with a predicted high of 95F. We shrugged it off, put on our hats and climbed toward the Lion Gate and the huge stone walls that legends claim the Cyclopes built.

The rampant lions carved in relief above the gate once had heads, perhaps of metal, but those have long been lost. Lions were guardian symbols, and the Lion Gate is the oldest sculpture of its kind in Europe. Beyond it, the terrain opened up to long views of mountains, distant farms and olive groves. The watchmen of Mycenae could see anyone approaching.

The Mycenaeans lived from 1600 to 1100 B.C. during the last part of the Bronze Age. They farmed, they sailed, they explored, imported, exported, created art and a system of writing. And they provided Homer with plenty of stories. They also were architects and builders of large palaces like the one we visited at Mycenae

We walked on top of what was left of the palace and saw how the remnants of walls outlined meeting rooms and living spaces within fortified walls that still stood tall.

On a lower level that may have led to craftsmen’s quarters, Mycenaean masons had formed enormous slabs of almond stone into a second gate at a corner of the citadel.

Ripe figs drooped and dropped from a tree against one of the stone walls. We couldn’t resist picking one up from the ground. The taste? Nothing, and our only disappointment of the day.

We followed the path from the heights of the palace down to a circle of stones.

It marked the first of Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations of the graves he believed held the remains of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. Schliemann, during twenty days in 1876, dug up three circular graves that held skeletons and treasures of the Mycenean glory days.

He donated it all to the people of Greece and we had seen the fruits of his excavations in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

But here in the place where we, like Schlieman, chose to believe Agamemnon and Clytemnestra schemed, we tried to imagine their lives. They had riches, power and beauty and still they were venal, petty and lethal. Do we know people like that today?

We finally gave in to the blistery heat and retreated from the citadel to the site’s air conditioned museum. We had company. A big dog wandered in, flopped down on the floor and rolled over on its back, and soon had playmates.

The museum showed us, in more compact displays, much of what we’d seen at the National Archaeological Museum. Somehow that made the wonders of Mycenae — not just the golden treasures but the small human and animal figures and the artistic pottery — easier to grasp. We asked if any were original and a museum worker said ruefully, “All stolen, or in the museum in Athens.”

We started back down the mountain, and clicked on the audiobook to hear if Achilles would resolve his feud with Agamemnon and fight for the Greeks against the Trojans. Before we got very far, a sign for Agamemnon’s tomb made us pull over. Our Mycenae tickets gave us access, and we walked a short path to a stone entryway into a hill.

A passage between the walls led to a tall door open to blackness within. A thin triangle opened over the massive lintel stone atop the door, lighting the inside. We found ourselves on the floor of a beehive of darkened stones rising over 40 feet.

There are eight of these tholos, or beehive tombs, around Mycenae that were thought to hold treasure stores as well as graves. This one is the best-preserved. The hill it’s built into was opened to lay the stones and then piled up with dirt again. It dates to around 1250 B.C. and probably had nothing to do with Agamemnon. Legend says that he lived earlier.

Argos, where we stopped for lunch, ranks as one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, with a history going back 7,000 years.

It’s also the legendary home of Odysseus’s friend and fellow warrior Diomedes who ruled Argos. The town’s ancient theater, now an archeological site, dates to 300-250 BC and held 20,000 people.

We parked in a treeless town square and spotted what looked like a taverna. No one sat at the outdoor tables on the square. But on this late afternoon, in a shaded courtyard of the Salvanos Cafe, we found locals finished with their work for the day and hungry, like us, for something simple.

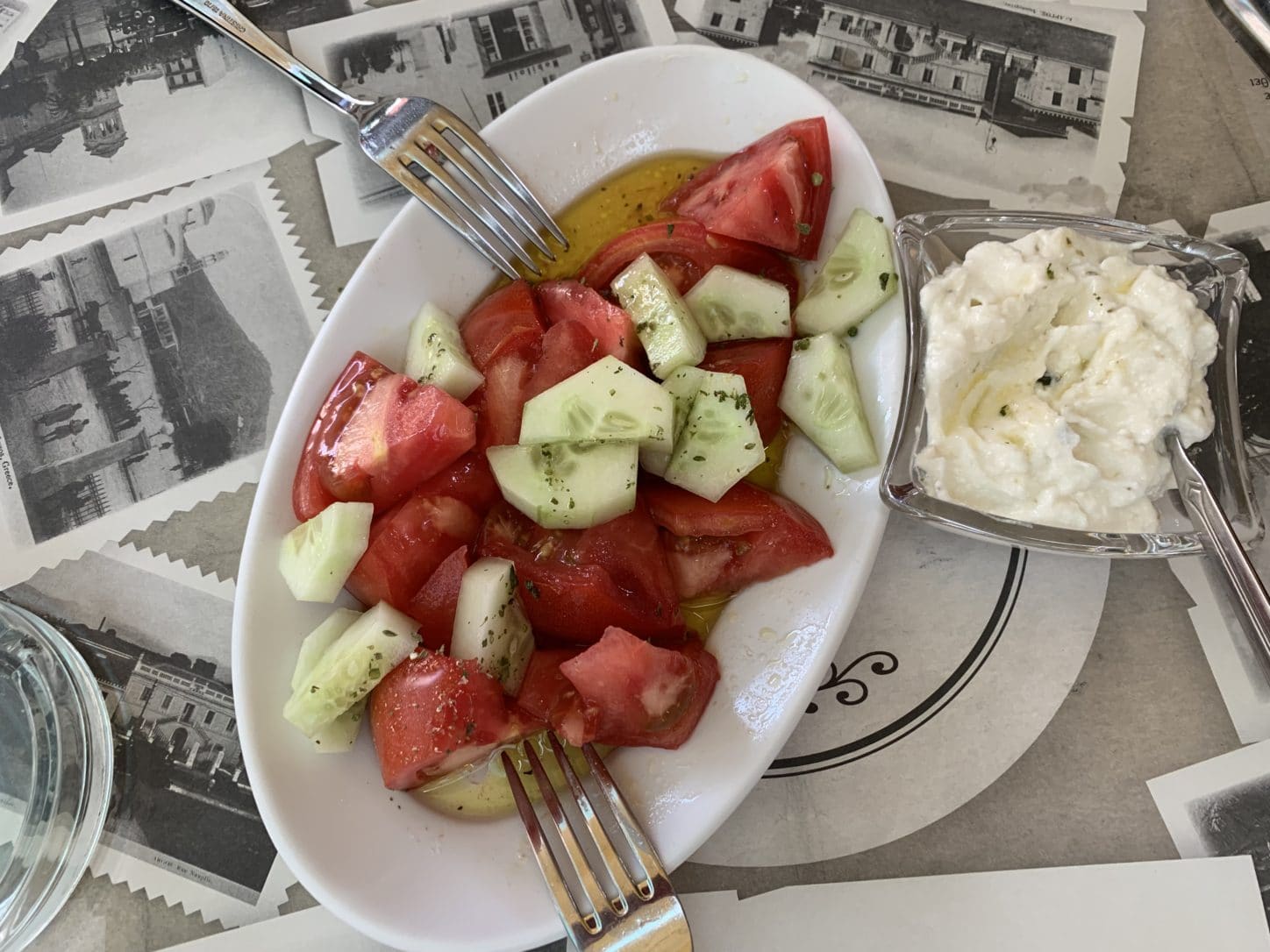

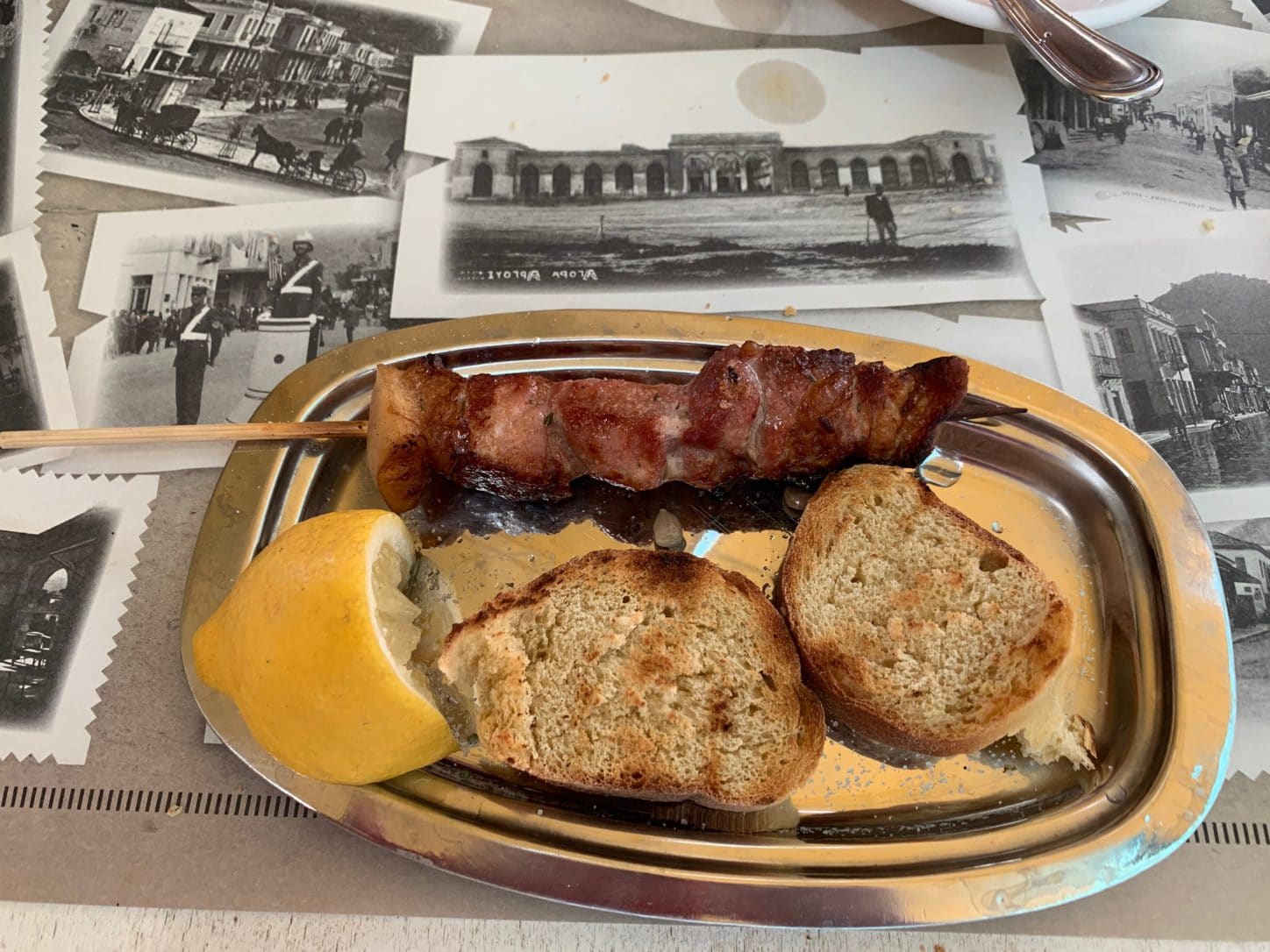

We ordered a tomato and cucumber salad and learned about tyrokafteri, a yoghurt and cheese dish. It’s similar to tzatziki, but with pepper instead of garlic, and lamb souvlaki on a skewer.

After lunch we followed the GPS up a climbing switchback road to the city’s acropolis, a hill that bears the name Larissa, and the mouldering Byzantine-Venetian fortress castle at its peak.

A gate leading to the fortress grounds hung open. There were no ticket takers, nor even any other cars. A couple on a motorcycle pulled up just after we did. We entered the gate with the fortress looming to our left A perimeter wall to our right gave a view across Argos all the way to Nafplio and the Argolic Gulf.

Back in Nafplio, we flopped into chairs at the harborfront restaurant-bar next to out hotel and sipped vodka-and-tonics.

We talked about what we’d seen at the archaeological sites, and what we’d heard in The Song of Achilles. The selfishness and destructive pride of Agamemnon and the stiff-necked stubbornness of Achilles showed us how little human nature has changed over the millennia. They offer great psychological insight, but also tell us how little we’ve learned from the past.

Later we returned to the Alkioni wine bar where Giorgianna hooked us on the Assyrtiko from Santorini and found a table at the Aiolos Taverna across the alleyway. They’re owned by the same people, and owe their names to Greek legend. Alkioni was the daughter of Aiolos, god of the winds that so bedeviled Odysseus attempting to sail home from Troy.

We had some more of the Assyrtiko, a bean and beet salad that was entirely too big, and delicious grilled sea bream. We were paying the bill when Georgianna appeared with two glasses and a small carafe of the Greek version of grappa, and after that we stumbled back to the hotel.

The next morning, we set out for Tiryns, which along with Mycenae is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Historians believe it served as the seaport gateway for Mycenae and is even older, dating to before the Bronze Age. History and legend were colliding like bumper cars inside our heads at that point.

The citadel of Tiryns, built on its acropolis, has massive limestone boulders forming its fortress walls, some weigh several tons, thicker than those at Mycenae.

Like those at Mycenae, legend tells us only the Cyclopes could have put them into place.

Archeologists are still working at Tiryns, and the day we were there a German team pointed us to the main chamber where the ruler held court.

The ruler’s throne was typically in what’s called the Great Megatron and Tiyrns provides a good example of how big these gathering places were. Even though these archaeological sites often seem like a jumble of big stones, often a thing or two appears, like this pink marble, that reminds you of how beautiful the palaces must have been.

From Tiryns we drove east 40 kilometers to ancient Epidaurus, a healing center called the Sanctuary of Asklepios, the earliest sanatorium complex and another UNESCO World Heritage site.

The complex includes a theater and that’s what we really wanted to see.

The theater at Epidaurus was built into a hillside in 330-320 BC and expanded in the 2nd century AD. 55 rows of seats face the stage, which has perfect acoustics apparently because of the way the seats are set.

Tourists like us took turns standing on stage, whispering to test whether the theater’s acoustics were as good as advertised.

Barbara began to train her voice as an acting student at the High School of Performing Arts and worked on it during her years in television news, but here all she had to do was use her softest whisper to project to the top. She stood center stage and Nick started climbing.

Nick stopped after the first tier, thirty-three rows up and heard her perfectly. He climbed to the top, and Barbara asked softly, “Can you still hear me?” Amazingly, he and all around him could.

And then a woman came up next to Barbara on the flat earth stage and began to sing softly. Her husband sat down to Nick and they both heard every word. When she finished her song, people in the theater clapped.

“I’ve always wanted to do something like that,” she told Barbara. She said she and her husband were from San Francisco and, like us, were sampling Greece both past and present.

That coming weekend, audiences of 12,000 would fill those same stone seats for two nights to see a presentation of Oresteia by Aeschylus. The 2,400-year-old theater is one of the venues for the Athens and Epidaurus theater festival for eight weeks every summer.

Now, close to the Peloponnese east coast on the Saronic Gulf, we headed to New Epidaurus to find a place near the water to eat lunch.

We loved the turquoise water but decided to pass on the brown sand beach.

The Hippocampus Taverna called to us. We took a table and learned that this hippocampus referred to the seahorse or sea monster. When we looked it up were surprised to find that the hippocampus, the critical part of our brain that deals with memory and navigation, is shaped like a seahorse. That’s how it got its name. But on to lunch.

[caption id="attachment_45362" align="aligncenter" width="1448"] Hippocampus Restaurant, New Epiduras, Greece. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

Hippocampus Restaurant, New Epiduras, Greece. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

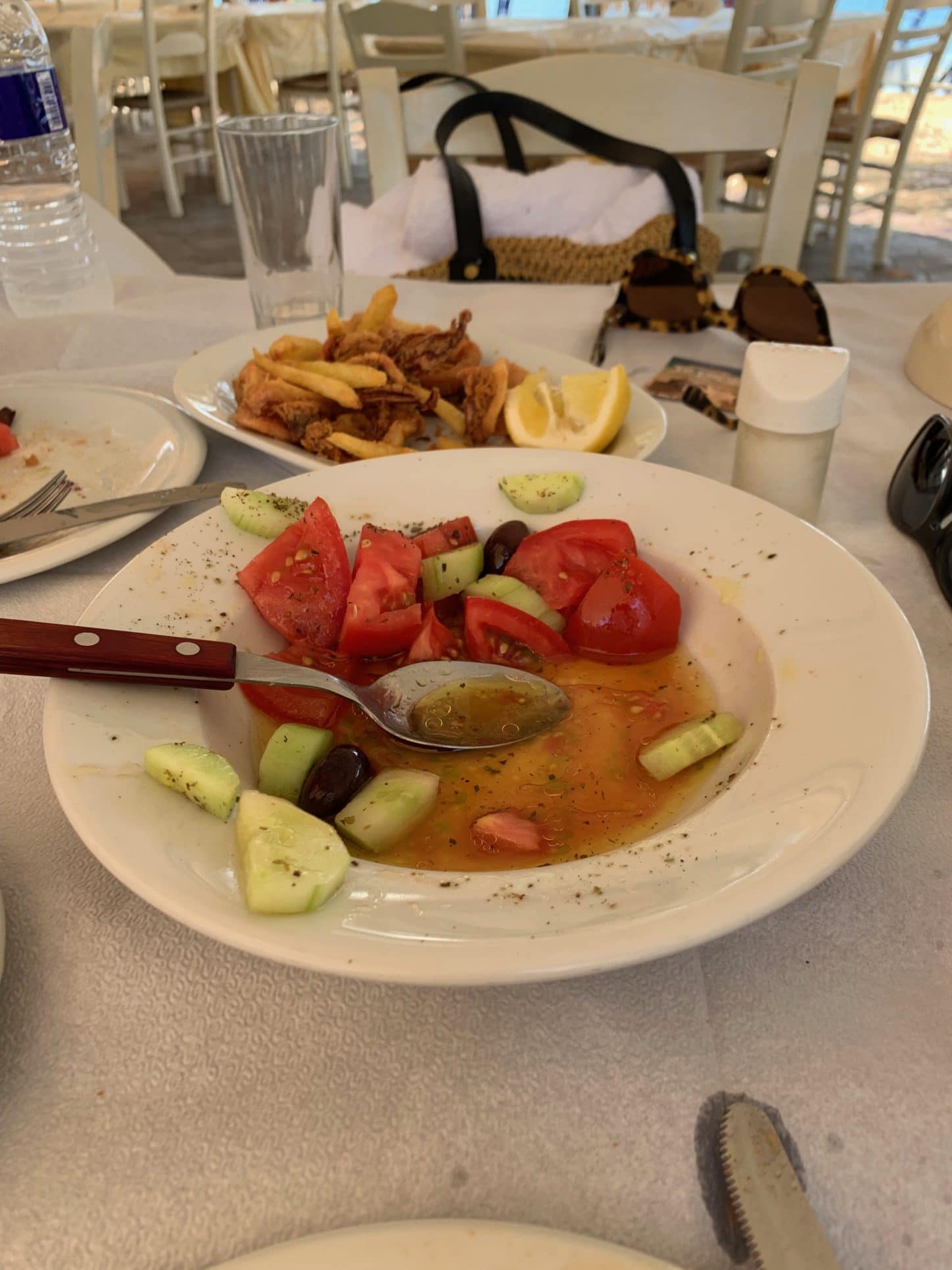

We enjoyed grilled calamari, a cucumber and tomato salad, and tyrokafteri. But unlike the dip we had in Argos, this had red peppers and tasted like a better version of pimento cheese spread.

That evening we watched another spectacular sunset in Napflio.

And then we went to eat at Omorfo Tavernaki, recommended by our guide in Athens, Panos Papageorgoplous, whose family comes from Napflio. “It’s my favorite taverna there,” he said.

By this time we’d figured out that the huge portions in the tavernas were like those in the Greek diners in New York and we decided to order moderately. Strangely, tavernas and restaurants in Greece specialize more in lamb than seafood. And that night, when we sat down they first told us they were out of fish. Then the waiters put their heads together and somehow came up with a couple of fresh and tasty white snapper. We left the side of baked potato topped with cheese untouched, though.

On Wednesday we and hit the tollway again, headed south to Sparti and Mystras, a drive of two hours or a little less

Panos, our tour guide in Athens, told us that Sparti, the modern town near the site of ancient Sparta, is the most conservative place in Greece, perhaps an outgrowth of its warrior culture. Another outgrowth is the Spartathlon.

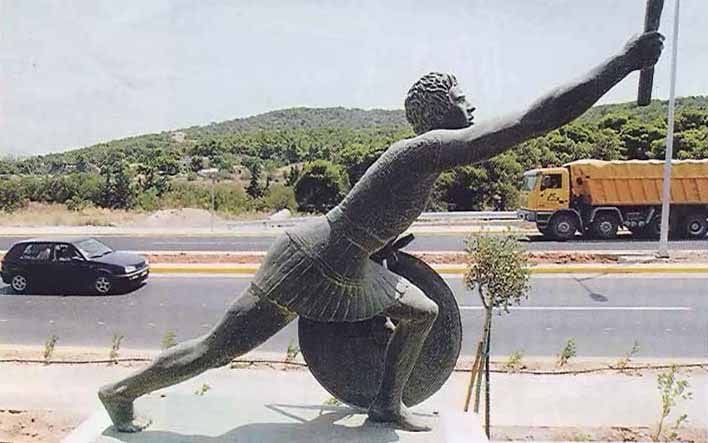

Legend says that in 490 B.C., Athens sent a runner to Sparta to ask for help fighting the Persians at Marathon. It’s 246 kilometers, or 153 miles, and Pheidippides arrived the day after he started. Some British Royal Air Force officers tried it in 1982, and three made it in under 40 hours. The next year it became an annual race, with the Greek winner Yiannis Kouros still holding the record of 20 hours and 25 minutes. We were glad we had the tollway.

Sparti wasn’t our goal, in any case. Mystras, also a UNESCO World Heritage site, was. It’s a Byzantine site a couple of miles west of Sparti toward the southern Peloponnese city of Kalamata. The wars between the Franks and Byzantines played out on the peninsula, and Mystras in the 15th century was a learning center and the most important Byzantine site outside of Constantinople.

Currents of reconciliation between the Eastern and Roman versions of the Christian church flowed through Mystras and went nowhere. Later the Ottoman Turks and Venetians fought over Mystras, too.

12-euro tickets in hand, we climbed stone steps on a path that took us to the lower town and Metropolis, the St. Demetrius Church, built in the 13th century.

Its bell tower loomed over us, its dangling rope awaiting the next bell ringer to sound a call to worship.

The small church, an ornate jumble of turrets and arches and adorned inside with rich frescoes, hosts services on special occasions.

“No flash pictures,” said the lady at the door. She told us she had relatives in Chicago, Florida, and New York City, and hoped to visit them some day.

We stopped at the small museum connected to the church and then climbed around the crumbling walls threading through the hills.

We returned to the car and took another of those switchback roads up and up to Mystras’s upper town and its hilltop citadel.

The view stretched for miles, back to Sparti and beyond.

The Cafe Xenia looked inviting on the way back down the mountain, and we stopped for lunch.

Later, back in Nafplio, we rewarded ourselves with vodka and tonics and the harbor view.

That night we returned to the Aiolos Taverna, where we had learned to split a starter before our grilled fish mains.

And once again Georgianna sent us home with a taste of grappa.

Thursday was our final day in Nafplio and we wanted to explore the nearby beaches. We set out after breakfast for Karathona, where we found a series of cabana colonies along a long arc of beach with pebbly sand.

Families sprawled under the umbrellas and a few kids were splashing in the water, but there was no one place that looked inviting. We returned to the car and headed for Drepano, a few kilometers east.

Following the GPS directions to the beach below the town, we wound up at campground central. Caravans, what we call campers or recreational vehicles in the United States, huddled under shade trees in a row of sites opposite the beach.

Umbrellas shaded lounge chairs at two places on the beach side. Following directions from a server, we walked five minutes to a taverna on the beach.

We kept eating the same salad because every tomato we had in Greece was bursting with midsummer freshness and we ordered a tyrokafteri and grilled squid to accompany it.

We were surprised when the owner brought us a dessert gift.

We chose the most inviting looking of the beachfronts at Deprano andtook lounge chairs under an umbrella for a cost of an iced tea and a lemonade, total 5 euros. We read our books and swam. The clear water showed a path between rocks into patches of sandy bottom.

And the show in the water was pretty good, too.

Nick watched a man make water spouts from a clenched fist and tried it. The man, he thought, would win the contest. Before heading back we explored the area around Vivari bay and found a spot fisherman seemed to like.

On the way back to Napflio, we drove up to Palamidi Castle, the 18th century Venetian fortress that overlooks the town and the Argolic Gulf.

The Ottoman Turks took it from the Venetians, and the Greeks took it from the Turks when they gained independence.

For some time the Greeks used it as a prison.

And if you’re a dedicated stair climber you can reach the fortress via the 999 steps its prisoners carved out of rock.

Nick made a much shorter climb to one of its eight bastions, the one named for Achilles. That’s Nick in the distance.

Along with the ruins and the views the most interesting — or maybe strangest — thing was a blonde woman in a red dress, looking at nothing but herself. She took selfies turning around and around.

Down below a couple called to her, “Arianna, stop. We have to go.” They called over and over and she ignored them with eyes for herself only. She seemed to pay scant attention to the beauty around her.

Back in Napflio, Nick took pleasure in our last sunset on the Peloponnese Peninsula

And Barbara went shopping. She’d spotted Iniochos, a shop in Napflio, with linen dresses that looked simple and cool for the 90F-plus heat.

Four Washington state women, Paula, Brynn, Leisa and Kaila, who had been on a cruise ship, had the same idea. And the local saleswoman Evie helped us all.

Dining that night at Arapakos, we met a tennis-playing family from Princeton, New Jersey.

And by this time, we were trying to learn the Greek alphabet so that we could decipher words. Dimitri and his brother Costa showed us the lower case letters and helped us correct our spelling.

Then it was back to the Agamemnon for our last night in Nafplio before we left the Peloponnese and drove up the western Greek coast to the island of Corfu.