by Barbara Nevins Taylor

I had a big birthday in July and wanted to do something special. Nick and I thought we might go to Mallorca to study Spanish, enjoy the water, sail, and explore the island’s beauty. But in May I checked the COVID information. Spain’s vaccination rate was just 18 percent then, and Mallorca had its first case of the Delta variant.

So that was out. Onward to Plan B.

City College of New York (CCNY) offered an online Spanish course in June. It crammed fourteen weeks into four, and we dived in as auditors. It was great, but we still wanted to travel. I told Nick I needed water, sun, and boating, in a place that was safe that we hadn’t visited before, to enjoy my birthday celebration.

I remembered Chincoteague, a sliver of land off the eastern shore of Virginia.

We hadn’t visited, but passed the turn-off many times as we headed down the Delmarva peninsula on U.S. 13 on our way to stay with friends at the beach in Nags Head, North Carolina. We read about the wild ponies and the sprawling oyster beds and that made it seem like the place to go. A five-hour drive from New York City, it crooked a finger at us and said, “Come on down.”

Nick Googled and found Fish Tales Fishing Charters. Jan picked up the phone when he called. She’s the booker and wife of Captain Pete Wallace, whom the Chincoteague vacation guide calls, “Chincoteague’s longest running charter boat captain.” Jan explained that because of COVID the company wasn’t mixing groups of people and that was fine for us.

Fish Tales “everything trip” cost $276 for four hours. That meant we could spend the time fishing, clamming and crabbing, or just sightseeing. Clamming, though, demanded low tide. On my birthday, that meant a 1 p.m. start, and that would give us a leisurely morning. “Bring socks,” Jan told him. “Or if you forget we’ll give you some.” We would learn why when we got there.

Fish Tales “everything trip” cost $276 for four hours. That meant we could spend the time fishing, clamming and crabbing, or just sightseeing. Clamming, though, demanded low tide. On my birthday, that meant a 1 p.m. start, and that would give us a leisurely morning. “Bring socks,” Jan told him. “Or if you forget we’ll give you some.” We would learn why when we got there.

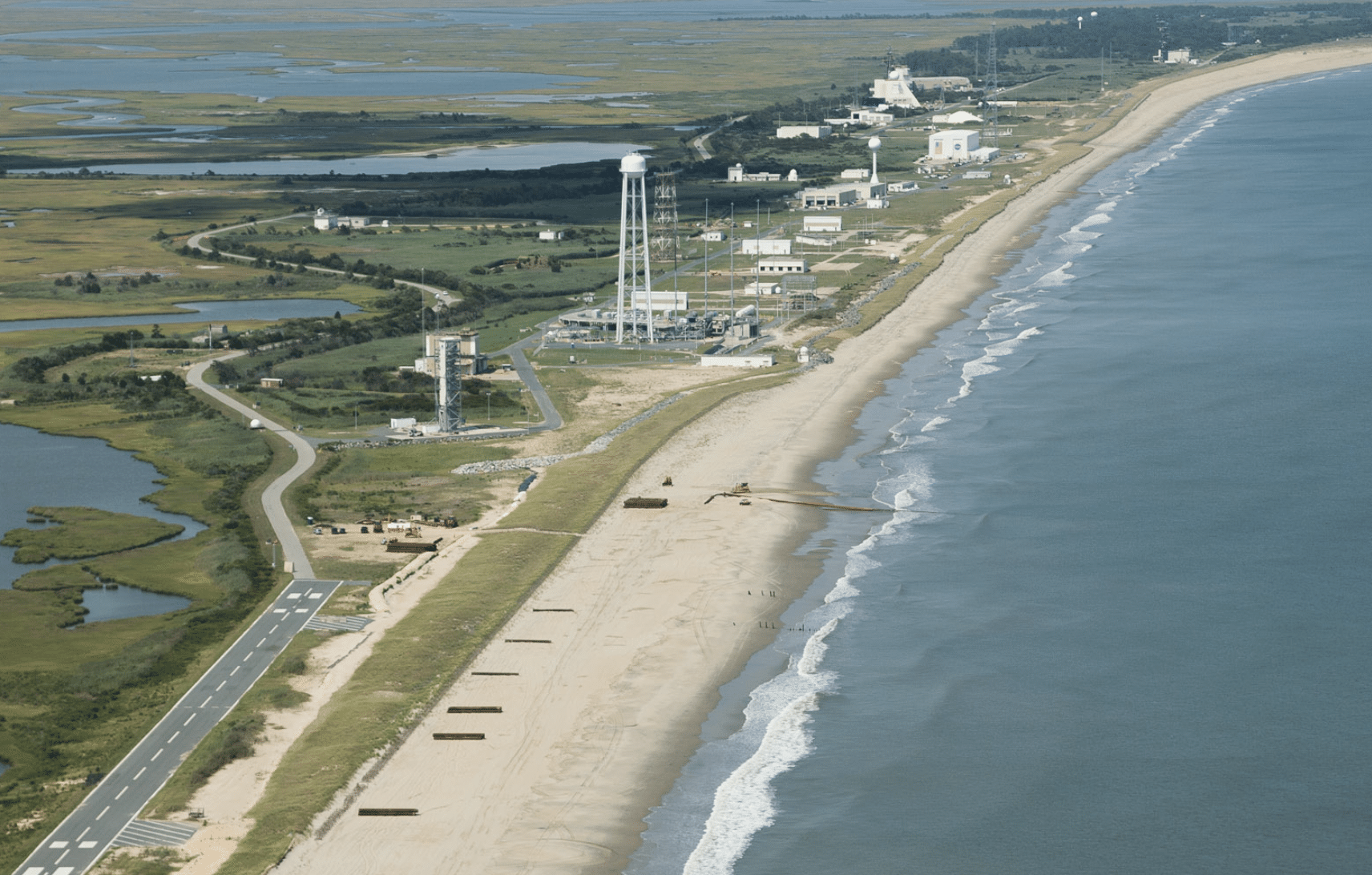

As a little girl my uncle Murray Robin took me, my sister and our cousins clamming in the Great South Bay on the south shore of Long Island near his home. I loved it, and that made Chincoteague even more appealing. We set out the day before my birthday and The Venice Sketchbook on Audible kept us entertained as we traveled through New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland. We turned off U.S. 13 onto Route 175, passed a naval air station and a forest of satellite dishes at the Wallops Island NASA facility.

Our road weariness melted away once we hit the causeway to Chincoteague.

The vista opened to a wide bay dotted with sandbars and low marshy grassland.

The flat landmass made us feel as though we had reached the end of the earth and that was okay. We drove onto Chincoteague and found our hotel, the Comfort Suites, on the bay. There are a few hotels on Chincoteague, as well as motels and bed-and-breakfasts. We chose the Comfort Suites because it offered a room with a terrace that overlooked the bay.

Before there were chain hotels the low marshland hinted at what Rachel Carson wrote about for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1947. She explained the importance of the island and its 37-mile-long neighbor, Assateague.

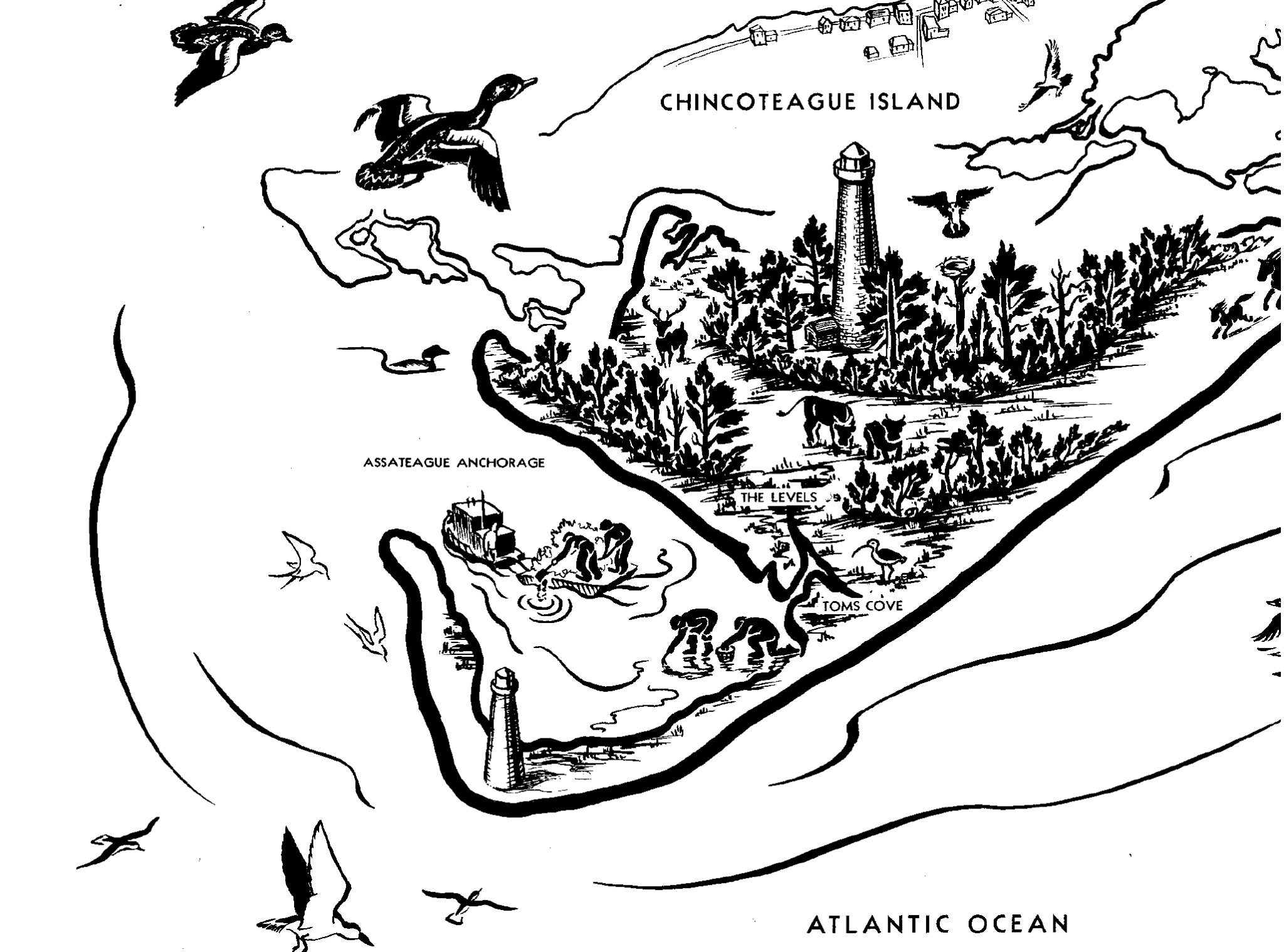

Assateague, a barrier island that protects Chincoteague and Wallops islands from the Atlantic, became a National Wildlife Refuge in 1943. The idea, Carson wrote, was to permanently protect a flyway in the mid-Atlantic for water fowl and other migrating birds. The Chincoteague Wildlife Refuge covers a third of Assateague Island in Virginia with a portion on the Maryland side of the island.

Carson described the island from a birds-eye view. She wrote, “Seen from the air, as the migrating waterfowl coming in from the north must see it, its eastern border is a wide ribbon of sand that curves around in a long arc at the southern end of the island to form a nearly enclosed harbor. Back from the beach the sand mounts into low dunes, and the hills of sand are little by little bound and restrained by the beach grasses and the low, succulent, sand-loving dune plants. As the vegetation increases, the dunes fall away into salt marshes, bordering the bay.”

Chincoteague itself is another story. The Native American Assateague tribe used the 9.3 mile long island for fishing, farming, and hunting. In 1608, the English claimed it as part of the Jamestown Colony and English settlers used it to raise crops and graze livestock.

It wasn’t until the 1800s that people actually began to live on the island as well as farm and fish. Oysters thrived in its shallows, potatoes grew on land, both businesses thrived and found markets in New York and elsewhere in the north. The trade became so profitable that Chincoteague refused, by a vote of 138 to 2, to secede from the Union during the Civil War.

Today small houses and shops line narrow streets close to the town center. Larger homes hidden in pine woods and marsh grass line the bays on the northwest and south sides of the island. Fast food and ice cream shops and family entertainment places run along Maddox Boulevard, the road that leads to Assateague. We gave it a pass on our late afternoon walk and headed down the quiet Main Street.

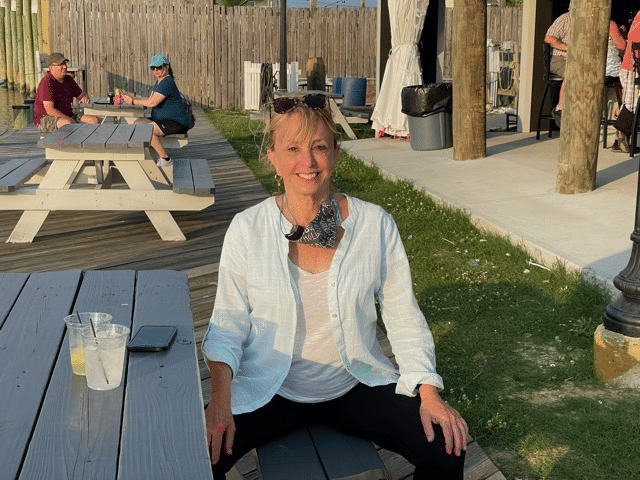

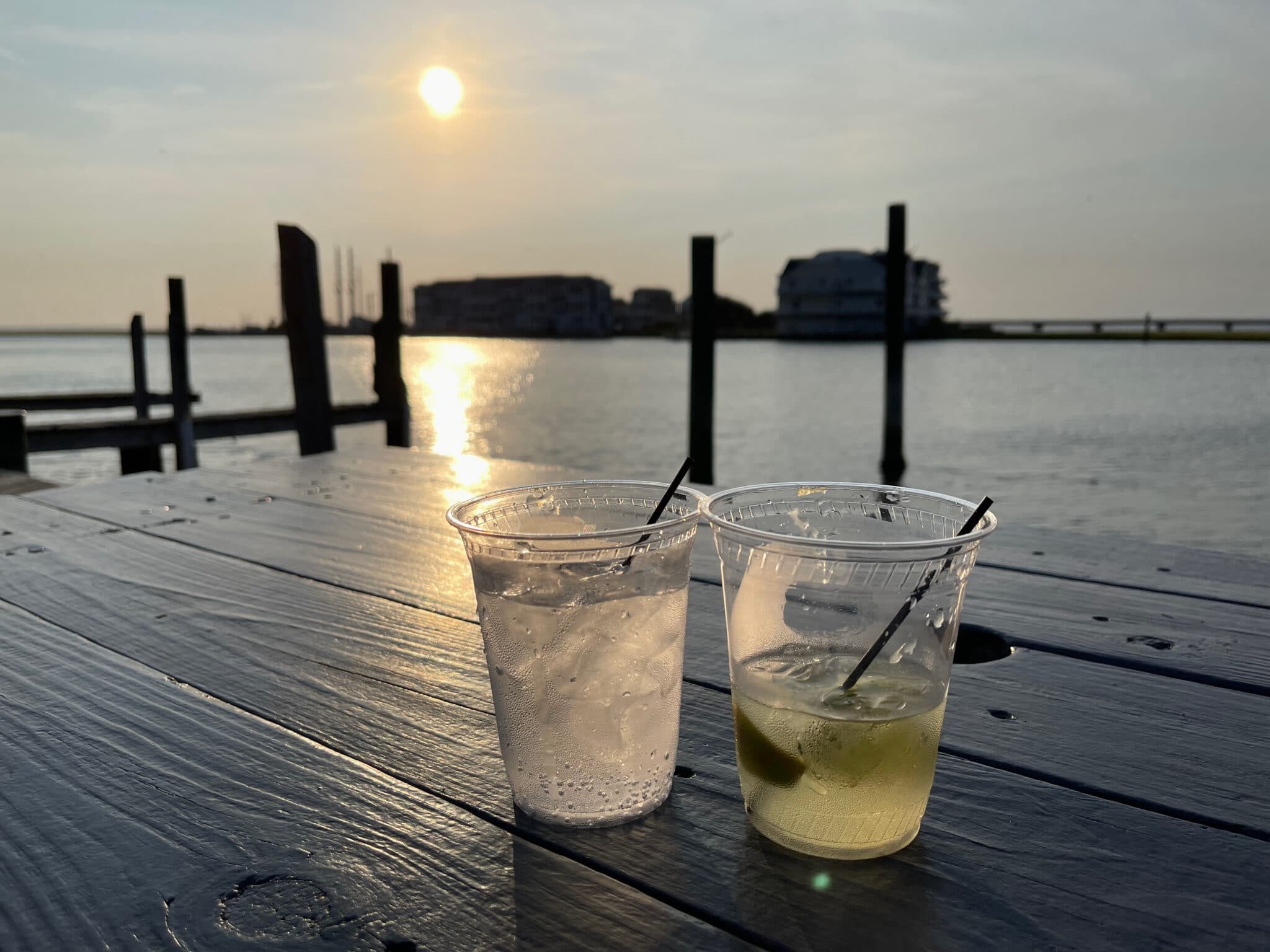

The one- and two-story buildings make the town feel peaceful and old-fashioned. But that changed when we walked to the water’s edge and spotted an outdoor bar. Don’s Seafood Restaurant was booked up inside, but a covered dining area on the dock seemed like a perfect place to have a drink.

The lively unmasked crowd at the bar kept us away but we found a place at a picnic table looking out to the bay and waited for a table for dinner.

When we got a spot at a table, it seemed safely far from others.

Nick kept his mask on his wrist just in case.

We ordered some oysters on the half shell to start, followed by some blackened flounder. To our surprise the oysters came in foil inside a cardboard box. “Wait, ” I said to the server. “We’re not taking out. We’re eating here.”

“That’s the way it comes,” she said, and we looked at each other and laughed.

We learned from our server Laura that all the food came to the outside bar this way. She pointed out that disaster loomed if servers had to carry trays loaded with stuff from the main restaurant across the gravel parking lot. At her suggestion we bought a bottle of Sauvignon blanc inside and brought it outside to enjoy in plastic cups with the paper-packaged meal we ate with plastic forks. The oysters tasted briny and had a nice tang. The fresh flounder came off a local fisherman’s boat and the chef dusted it with hot paprika and cayenne and other blackening spices. A few hush puppies on the side gave the meal an added Southern taste.

On my birthday morning, we woke up to watch the birds fly across the bay and set out to explore.

The wild ponies beckoned. It was the day of the annual pony roundup and we hoped to catch a glimpse of the horses.

The National Park Service calls the ponies feral animals and that means they are the wild descendants of horses that had been domesticated at one time.

Locals tell a couple of stories about how the ponies landed on Assateague Island. One story says that the horses survived an ancient shipwreck off the Virginia coast but no records confirm that. The other, more probable story, has it that horses were brought out to Assateague in the 17th century by owners who wanted to avoid taxes on livestock. The horses then went wild and lived on sea grass and berries.

The horses have their own organizational scheme. They divided themselves up into bands of two to twelve and each band has a home range on the island. But the National Park Service limits the size of the adult herd to 150 to protect other wildlife and island natural resources.

That’s where the pony roundup comes in. On the Virginia side of the island, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company owns and manages the horses. The last week of July, they round up the horses and swim them from Assateague to Chincoteague for the “Pony Penning” festival. The next day they hold an auction and sell off the foals and the money supports the fire company.

[caption id="attachment_47068" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Ponies get herded to corrals and are auctioned off. Photo by Leonard J. De Francisci. Creative Commons License.

Ponies get herded to corrals and are auctioned off. Photo by Leonard J. De Francisci. Creative Commons License.

Since COVID the auctions have been online, but the roundup continues. We saw penned ponies and one in particular was furious.

We also explored a little of Assateague.

[caption id="attachment_47064" align="aligncenter" width="2048"] The adult snowy egret has black legs and yellow feet. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

The adult snowy egret has black legs and yellow feet. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

Most tourists seemed to come for the beach, which is long and quite beautiful.

We wanted to explore more but ran out of time. We picked up boxed lunches of shrimp salad sandwiches from Captain Zack’s seafood shack and headed to the marina.

Boat Captain Chris Milliron and his mate Ben Pavlik greeted us with the news that they were both fully vaccinated against COVID. We liked them immediately.

Chris gave us a safety rundown and warned we would be riding into the waves. We had a great bumpy ride with cool spray pinging our faces and for a few seconds I wondered if seasickness would be part of my birthday celebration. But then I reminded myself to keep my eyes on the horizon. All was well as he steered the boat to a spot were other fisherman had caught flounder earlier in the day.

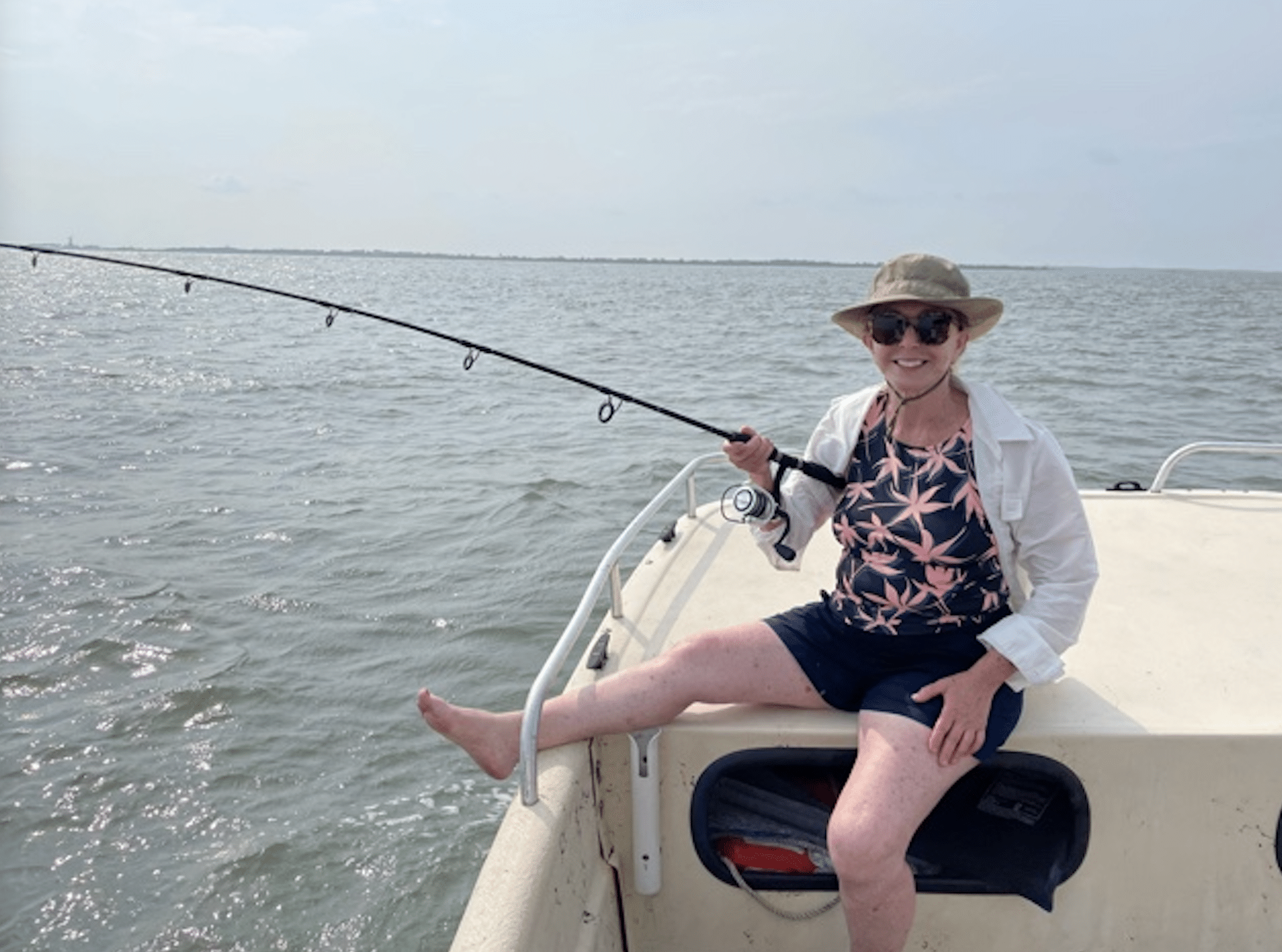

Nick wrote a book about fishing, Bass Wars, grew up in Florida and knows a little about fishing. Me, not so much. But I like the idea of it. Ben set me up with the rod, and of course, I held it the wrong way. No one bothered to tell me that for a quite bit.

Ben explained that we wanted our sinkers and hooks to hit the bottom because that’s where we would find flounder. Sea trout, kingfish, croaker and spot also swim in the shallows of Chincoteague Bay in the summer. I tried to coax the fish to my line as I let it out and felt the slight bump as it hit bottom. It seemed promising. But the fish didn’t bite.

Chris and Ben make a living taking tourists fishing in the summer, and duck hunting in the winter. When the Chincoteague season is over, Chris travels back to his home base in Detroit and takes fishermen out on the lakes in Michigan. In the winter he leads duck hunting groups off of Chincoteague So these guys know the water and wanted satisfied clients.

But for us, the fishing was really an excuse to be here getting slightly wet and salty and basking in the sweet air. I loved being on the water in the middle of the beautiful, fragile ecosystem. The small boat gave us an eye level view of grassy waterfowl hideaways and the nooks and crannies where small animals wandered. It also gave a chance to begin to understand the way the wind, and water shape and reshape the islands and inlets

Chris steered the boat under the causeway up into Mosquito Creek to see if we would have better luck. He told us the local history about a minor Civil War battle near the inlet, but we still didn’t catch fish.

But as we sat in the creek bordered by marsh grass, Navy E-2c Hawkeye surveillance planes flew overhead. It felt slightly surreal. Teams of pilots in the Hawkeyes went round and round bumping in mock landings on a runway nearby and taking off again. They were practicing aircraft carrier landings.

That morning we had met a group of pilots staying at our hotel and they explained that they did repeated rotations, changing positions in the plane and taking turns piloting after the runway bump. “Is it fun?” I asked after they explained. “Yes,” they said in unison and we all laughed.

But where were our fish? Chris moved us into another inlet and still nothing. Finally, he suggested that we take a break and go clamming at Tom’s Cove off of Assateague.

When the tide pulls back at Tom’s Cove it leaves an expanse of mud that beckons clammers. That’s where the socks came in. You may remember that we were told to bring socks. Chris and Ben suggested we used the cheap socks they had and we hopped out of the boat into the water and tromped into the mud. We laughed, scrambled for balance and slithered through the mud. Our toes and feet sunk down and we tried to move them around to feel for the big Quahog clams that live here. By the time Chris suggested we try one more fishing spot, our hands and legs were covered in mud.

We had a bucket of almost two dozen clams and I began to think about how to cook them.

Chris had learned from his boss that fish were biting off the hook of Assateague Island.

And sure enough the fish finally answered our calls. I caught spot fish and croaker all too small to keep. But Nick landed a kingfish and it felt like a victory for us all.

By the time we left the dock that afternoon, Ben had cleaned and filleted the kingfish and washed the clams so that everything was ready to cook. It was a perfect day. That night we celebrated at Bill’s Prime Seafood and Steak. We enjoyed more local flounder, crab cakes and hush puppies. It wasn’t Mallorca. But the all-American water big birthday was special enough.

The “furious” pony was Riptide, the most popular and famous stallion in the herd. He was mad at being separated from his mates, who went over with their foals for the auction!

How wonderful to know this!! Are you part of the pony roundup?