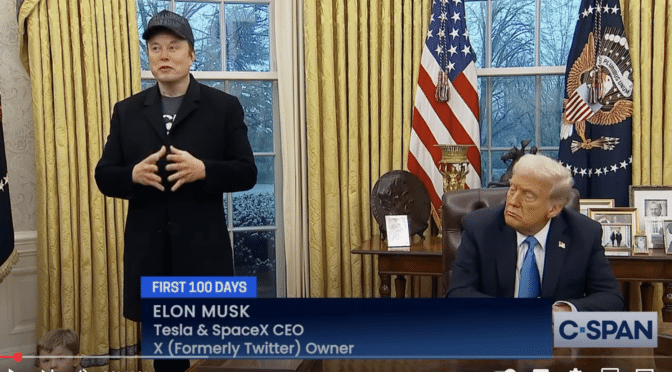

by Nick Taylor

The movers finally came for Mom’s piano. Not movers, in this case. More like morticians we called to put the old piano down. It was with me a long time.

It’s there in one of the earliest picture I have of myself. I’m standing, head cocked to one side, in the living room of my parents’ house in Waynesville, North Carolina. I must be five or six years old. The tinsel-strung tree to one side shows it’s Christmas morning and my present, a bicycle, leans against the front of that piano.

It was a Leonard upright, made in Detroit, where she met my father, an immigrant from Great Britain, in the 1930s. It was probably her mother’s piano; Mom was born in 1909 so would have been just a teenager when Leonard stopped making upright pianos in the mid-1920s. That meant it was 100 years old, give or take. It lost a pedal somewhere along the way, but the wood finish was still good and it had clean art deco lines.

My mother played a little, but she had high hopes for my relationship with that piano. It came with us to southwest Florida when we moved there in 1953.

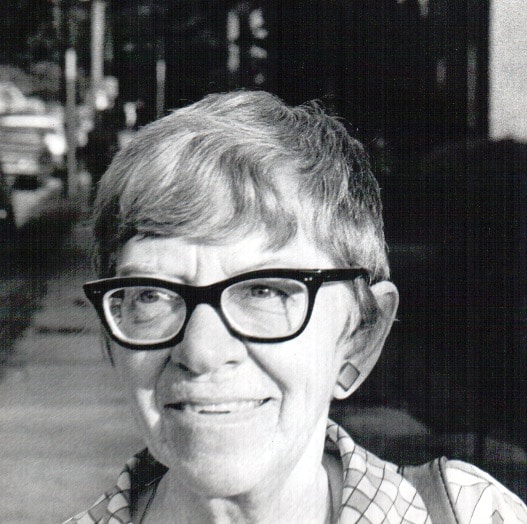

My mom Clare Taylor

She signed me up for piano lessons as soon as I was big enough to reach the pedals. But Ft. Myers Beach beckoned me outside, to the warm sand and soft surf just minutes from our house. The wind in the palms practically sang, “Don’t stay inside and practice the piano.” The fact that I had no ear for music didn’t help.

The piano became mine in the 1970s.

My parents Jack and Clare Taylor in Chapala, Mexico.

Mom and Dad moved to Mexico and the piano moved into my turn-of-the-century apartment in an old section of Atlanta. Barbara’s father played it when she and I were married there in 1983. It came with us when we moved to New York a year later. A crane hoisted it from the street below and movers guided it through a top floor window of our duplex apartment at the top of the four-story townhouse we now own. Since 1984 it occupied a corner of our living room.

Mom’s piano in our living room. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com.

We hired piano players for a party or two. I had it tuned once. Unused sheet music and an old Scrabble set hid in the bench seat. A vase and a ceramic piece memoralizing the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Centers stood on the piano top. Plants clustered at one end. It took up some space that we could use. I started to consider it a burden.

But it was my mother’s piano. She died in 1990 and can’t scold me anymore, but I agonized. She cared enough about it to keep it all those years, and then to pass it on to me. I knew its value was mostly sentimental. Ancient uprights can’t find buyers. We were going to give it away, but for the $6,000 it would cost for the crane to take it out through the window it came in we could buy somebody a new piano.

That left a piano removal service. Google “piano removal” and what comes up is “junk removal.” I called Junkluggers of New York. They sent an estimate that I signed and returned. A date was set. On the morning it was supposed to happen, a supervisor called to say he’d looked at the job and believed his guys couldn’t deal with the weight of a piano down three flights of narrow 19th century townhouse stairs. He gave me two other company names.

I called Magic Piano Movers. “How big is it?” asked Nargiza Turayeva who answered the phone. I measured it, 57 inches wide, 40 high, and 25 deep. Not a big piano, and I once again, as I did every time I looked at it, admired its spare and economical lines. No frills. Its clean lines didn’t sway me this time, though.

But I thought they were going to back out, too, when Nargiza called me anxiously the afternoon before the job. She was worried. Her boss wanted to see pictures of the piano and our stairs. I set my iPhone camera to video, aimed it at the piano and then followed the route of narrow stairs and tight turns it would have to travel down to the front door and the street in a house built in the 1840s. Nargiza texted to say she’d received the video. The next day, Monday, three big men arrived at the appointed hour. I met them at the downstairs door and said, “I see it’s not magic that moves the piano, but brute strength.”

I didn’t mention skill, but these men had it. Jonathan, Sebastian, and Daniel were originally from Colombia and spoke Spanish to each other as they worked. They knew what they were doing. From a small tool bag they took out an electric drill and started undoing what workers in a factory in Detroit had done a hundred years before. They opened and took off the lid, pulled out the assembly of hammers that hit the strings, took the wood front off the harp, unfastened and removed the keyboard. Soon what had been the piano was only the harp and strings assembly lodged in its now skinny wooden case. The harp or plate was cast iron, though, so what was left was heavy.

Taking out the keyboard. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com.

Soon they had it strapped to a cushioning pallet with a pad underneath.

Then they headed for the stairs. Jonathan, the chief of the crew, said, “Uno, dos, tres,” and they took on its weight.

And then what was left of it was down there on the street, the rest of it already taken down in garbage bags.

What do I think now that Mom’s piano’s gone? I don’t feel as guilty as I thought I’d feel. Seeing the object I’d known all those years reduced to its component parts told me that it was just an object, after all. Its beauty lay in the sounds it could make under the right hands, and I never learned to make them. As mute furniture it wasn’t much. It was just the piano’s ghost the Colombian-American Magic Piano Movers carried away the other day, and I hope it rests in peace.