We started our second day in Lisbon feeling a little more sure-footed, especially after breakfast in the 138 Liberdade Hotel’s lovely garden.

The MAAT Museum on the outskirts of Lisbon topped our activity list for the day. But our first mission when we hit the streets was to find Lisboa (Portuguese for Lisbon) cards.

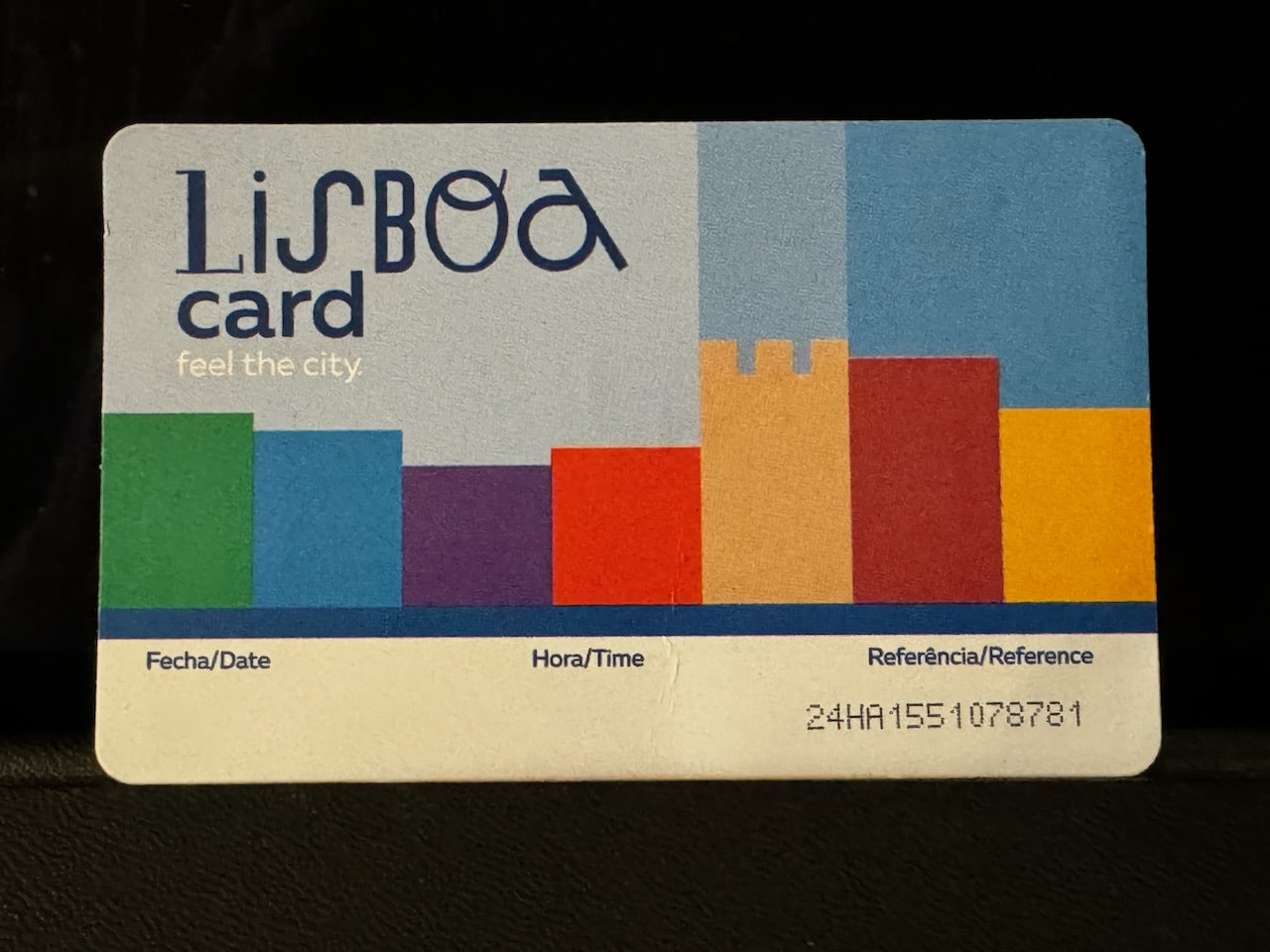

The Lisboa card gives tourists, for a flat fee, rides on public transportation, entry to museums and other cultural sites, and discounts elsewhere. The problem was finding one. None of the kiosks at Rossio Square or other places that were supposed to sell them were open on a Monday morning.

Finally a police officer directed us to Praça de Comércio — Commercial Square — at the Tagus River. It felt like we were getting friendly with the city because we’d been here the day before. We bought two 24-hour cards for 54 euros and with them in hand boarded the E15 tram headed west.

Our target was historic Belém about five miles from the central city. Belém served as Portugal’s seat of government in the wake of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which somehow spared it while wrecking the rest of the city.

We passed the port of Lisbon and the 25th of April Bridge, named for the military coup of April 25, 1974. The movement was called the Carnation Revolution and overthrew the 41-year dictatorship of Antonio Salazar. It ushered in democracy, political reforms and put an end to Portugal’s colonial era.

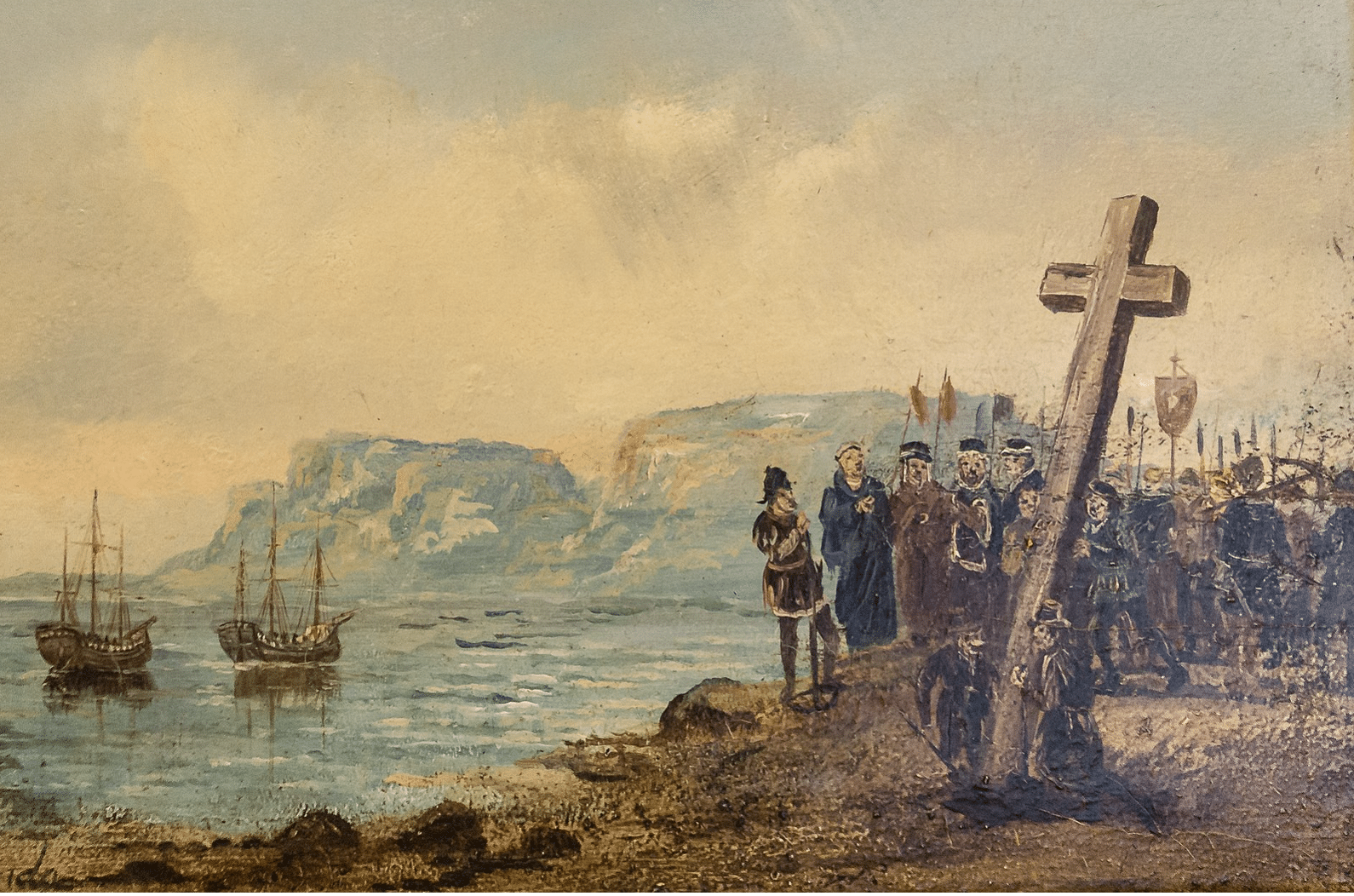

Earlier in the city’s history, Belém was Lisbon’s port during the 15th and 16th centuries when Portuguese explorers including Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan sailed the world and discovered the sea routes to East Africa, India and Brazil.

Da Gama gets a lot of the credit, or blame, for opening exploration that led to colonialism. But Bartolomeu Diaz was the first to cross the tip of Africa and Cape Horn. Ten years later, with four ships built in Belém Vasca de Gama sailed around Cape Horn and ultimately across the Indian Ocean to India

The exploration continued the Portuguese and Christian kings’ rivalry with North Africans and Arabs for trade and control of the sea. Ultimately, Portuguese prowess at sea made the country a rich, colonial power that created and controlled trade routes for slaves, gold and spices.

Our trip on the tram was much more modest. We were going to explore the MAAT — the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology — about five miles from Praça de Comércio.

This museum is worth a visit, but you have to do a little walking to get there.

When you leave the tram, you climb stairs to an overpass that spans the railroad tracks. On the other side of the bridge there’s a riverfront park and a path to the MAAT.

A white sculpture called Centro Tejo (Tejo is Portuguese for Tagus) sits on an old pier outside the first museum building.

Pedro Cabrito Reis created the sculpture with aluminum tubes and neon lights and asked specifically for it to be placed outside of the energy plant that forms the core of the first part of the MAAT.

The museum is ambitious. Art, architecture and technology covers a lot of ground and the museum, which opened only in 2016 as a project of the Portuguese energy company EDP, is divided into two parts. First you enter the disused power plant repurposed as a museum of electricity. Large-scale technology is what they’re talking about here. The scene smacked us in the face as soon as we walked through the door. We take electricity for granted but the old industrial pipes looked like a modern sculpture.

From an upper balcony we looked down on the kind of grandeur we’d never give much thought. This machinery created the environments we children of the so-called First World grew up in, and shaped us just as much as ancient art.

We strolled through another section devoted to boilers and tools used when the hard work of making fire and heat was done by hand and analog dials monitored what was happening: 20th Century technology.

There is some art and modern sculpture in the power plant portion.

But the bulk of the modern appears in the grand new building that shows a different face to the museum visitor.

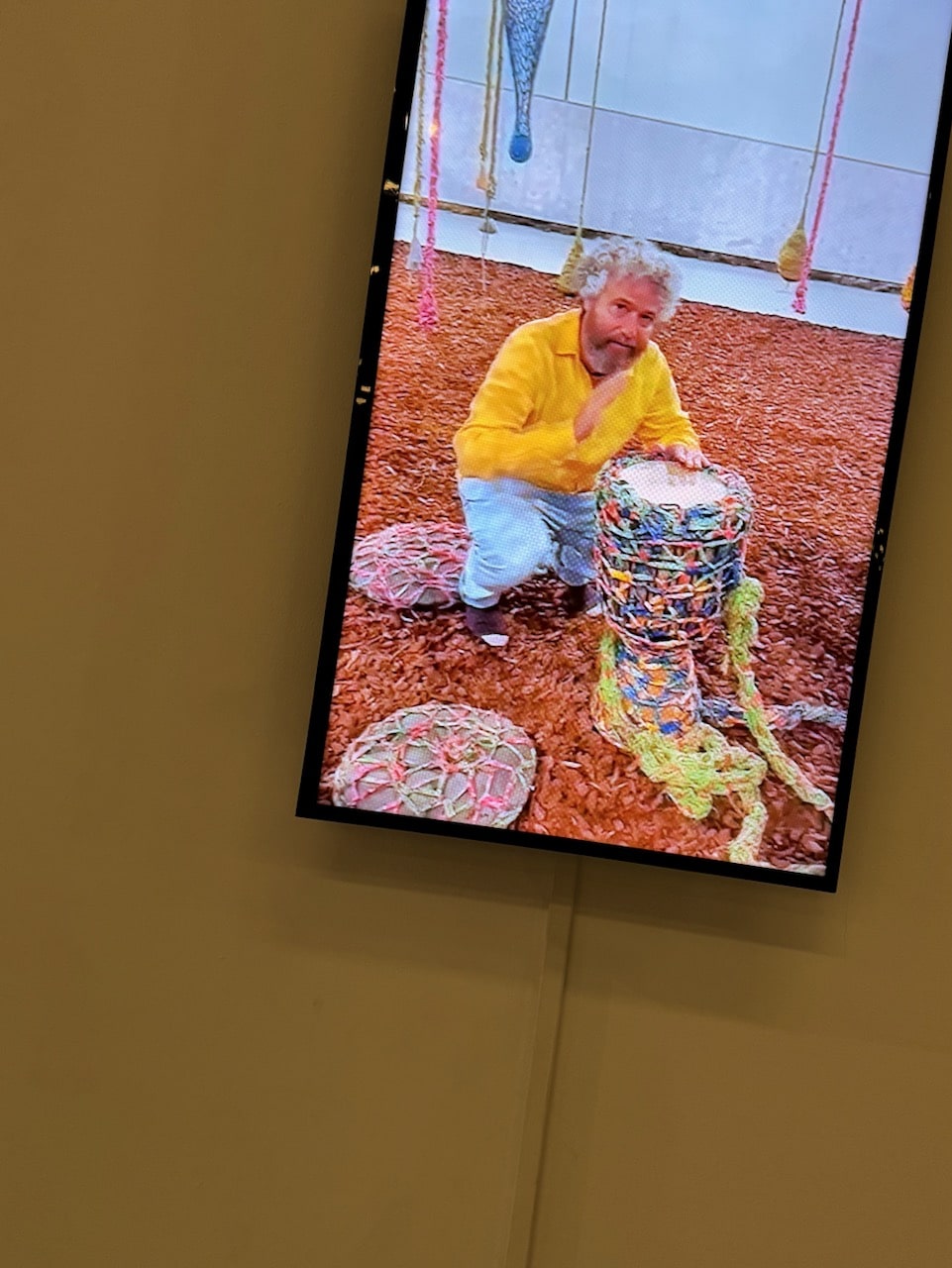

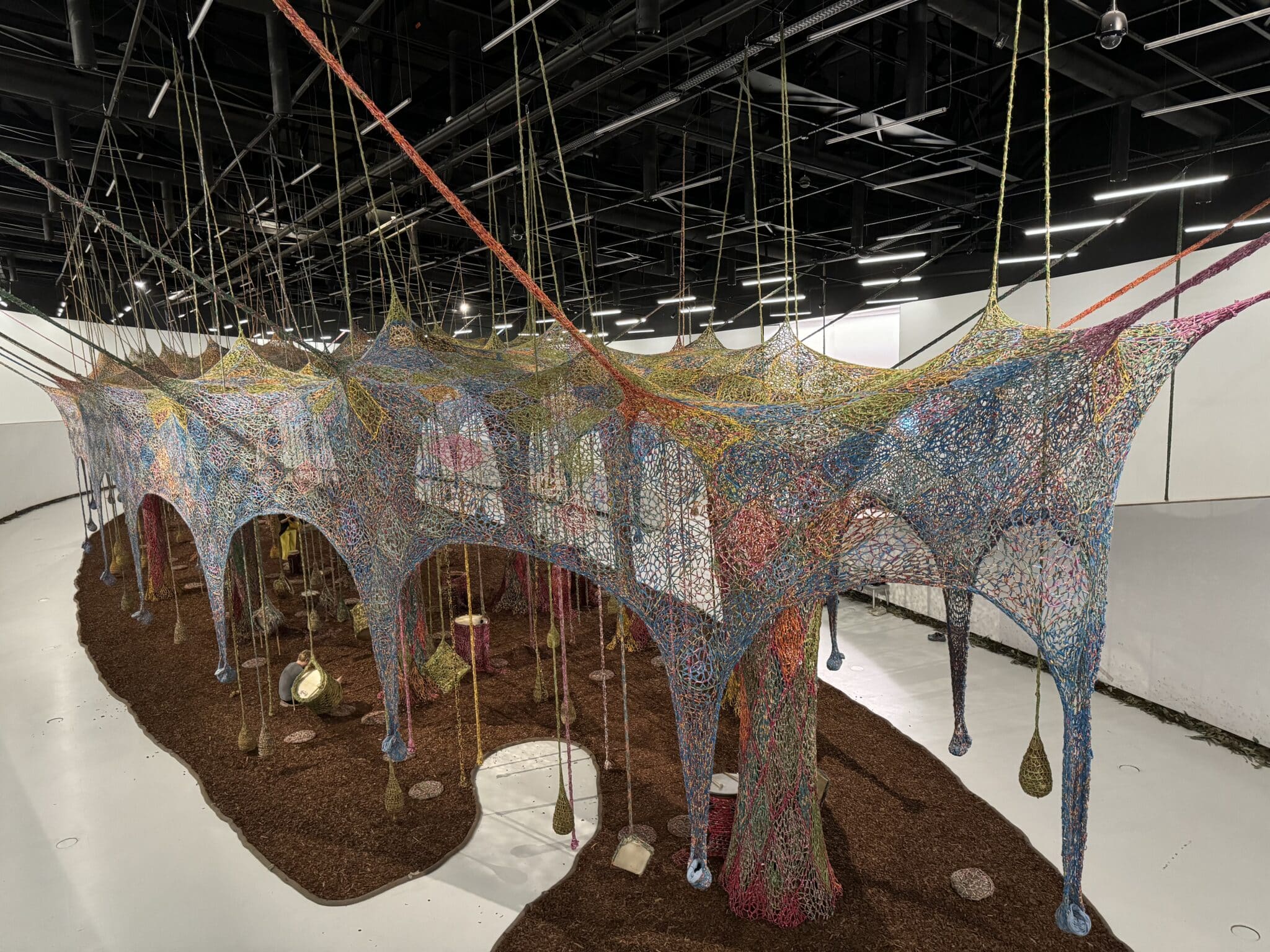

Visitors also see a different face, or faces, inside the new section. The big show when we were there was an installation by Brazil’s Ernesto Neto.

Neto created an art installation not just to be seen but to be felt and experienced from within.

You had to take off your shoes to feel the “jungle floor” under your feet, and there were drums to play among the “trees.” It felt as though we were drumming in a Brazilian rain forest created by the artist.

After we immersed ourselves in Neto’s world, we stopped in the gallery that showed French photographer Nicolas Floc’h’s underwater shots.

He saw gargoyles and witches in seaweed and sea grasses, but Nick’s favorite shot was of decorative barnacles on an underwater structure.

Outside again, two more things caught our attention.

A giant ring, a blowup of an engagement ring called Solitaire, is by Joana Vasconcelos. It’s made up of 110 car wheel rims and 1449 crystal whisky glasses as the diamond.

And at a fenced-off pier, we saw a warning in Portuguese that didn’t need translation.

We headed back across the bridge to the No. 15 tram and central Lisbon. Pau de Canela provided another late afternoon snack of sweet and savory pastries, and a nearby Zara satisfied our urge to shop.

That night we took another cab ride up the hills to another neighborhood, Barrio Alto, and another really good meal. The restaurant was BAHR, an acronym for the Barrio Alto Hotel Restaurant. From its terrace on the top floor, it had a beautiful view of the Targus.

We hadn’t been able to book a reservation on the terrace at BAHR, so we ate in the dining room. Our hostess Irina suggested we could have dessert out there after the meal.

We began by sharing ribbons of squid and beans.

Barbara chose sea bass for her main.

Nick had pork with beans.

True to her word, Irina led us out to the terrace for desert.

A young woman, Gabby, from Duke University via Long Island, sat next to us having a solo dinner and writing in a notebook. She heard us talking about writing, and said was working on a novel. She shared her experiences at school, and her plans. “What’s your advice for a young writer,” she asked. We’re not novelists, but our advice goes for everything. “Keep writing,” Nick said.

We were ready for the next chapter and our third day in Lisbon. A cab took us back down the hill past Restaurdores Square and on to Avenida da Liberdade and Hotel 138.