Discover Sardinia Part Two

by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

The idea of the Nuragi fascinated us before we even set foot in Sardinia. A civilization that had existed nowhere else, and we’d never even heard of it. We wanted to find out as much as we could about the Nuragi.

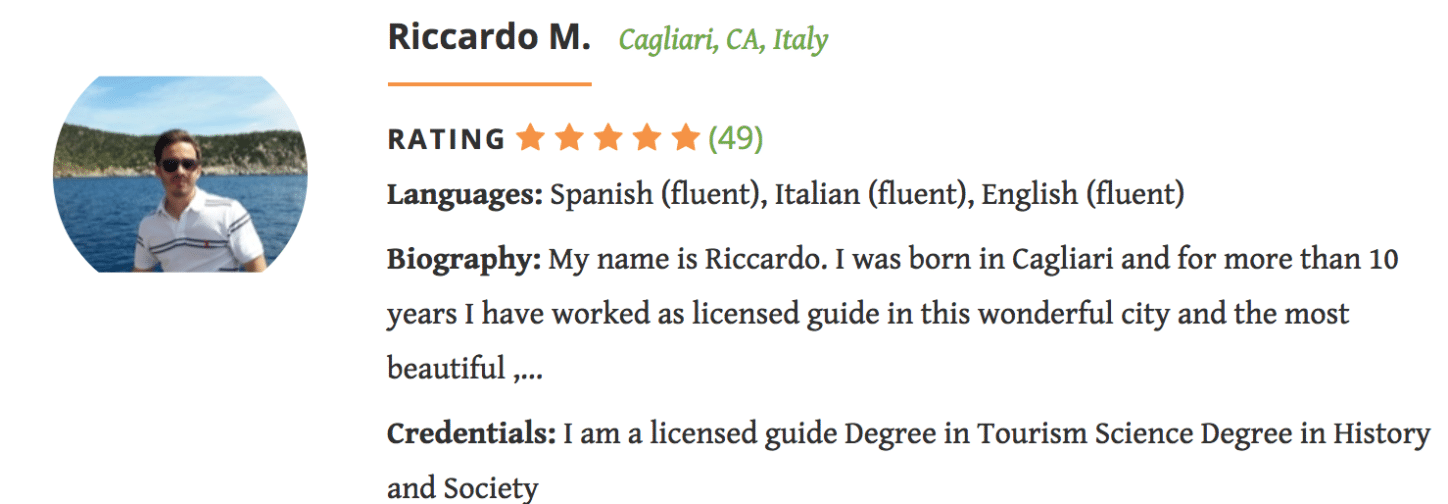

Then during our planning, we noticed on TripAdvisor that other travelers raved about Riccardo Mingola , a private tour guide, and before we left New York, we lined him up to take us Su Nuraxi, the Nuragic site at Barumini north of Cagliari.

Riccardo met us at 9:15 in front of the Palazzo Dessy. We walked down to the marina and hopped in his car for the hour-long trip to Barumini.

Riccardo, a Cagliari native, clearly loves his home town and its island. He earned masters degrees in History and Society and Tourism Science to help him share his passion with others.

On our travels, we discovered that one of the great things about riding around with locals, wherever you are, is that they talk about life in general and you get to learn a lot about the place you’re visiting.

Riccardo bemoaned Sardinia’s economy. “I’m thirty-seven years old, married and have a new baby girl,” he said. “I’m lucky. Most of my friends can’t afford to get married. This generation is different from our parents’ generation. People my age don’t have a steady job, or make enough money.” In fact, the island with 1.7 million people has overall unemployment of about 18.6 percent, which leaves a lot of room for honest complaint.

He blamed the European Union and what he sees as the lack of control that Italy and Sardinia have over their economies. “Imagine if the U.S. couldn’t control the Federal Reserve,” he said indignantly.

But he quickly turned away from money matters and pointed to the hilly mountains that loomed in front of us. “This is called the Marmilla Region because the mountains are shaped like breasts,” he explained with not a hint of smile

We left the highway and turned onto a road that led through a series of small towns.

“This is what I love,” he said, pointing to murals painted on the walls of houses that we passed. “You’ll see when you go around Sardinia that the villages have murals.” Of course, Barbara had to get out and take photos.

Then we drove on a bit, and turned into a parking lot below a hill. This was what we had come to see.

The hill was just a hill when archeologist Giovanni Lilliu began digging there in the 1940s. The Nuragic remains that he unearthed by 1952 proved to be the most complete example of what these Bronze Age people built between 1600 and 1200 BC and inhabited into the Christian era.

Nuragi lived all over Sardinia and more than 7,000 sites have been discovered so far. But Barumini, Riccardo said, would show us more than any other not just where, but how these people lived. UNESCO designated it a World Heritage site and we soon would see why.

We walked to what looked at first like a pile of tumbled stones. In fact “Nuragi” derives from words for “pile of stones” and “cavity,” and as we grew closer it took shape as a complex of conical towers at the crest of a low hilltop with a command of the surrounding countryside.

Riccardo led us to the central complex first. He explained as we passed through the “village” of outbuildings where regular Nuragi lived that he wanted us to see what had anchored the site and, even with its top now open to the sky, was most original.

We followed him up a set of steps to a platform that provided access to the central tower. Once over 60 feet high, the loss of its upmost of three chambers enclosed by a domed top shaved it down to about 50 feet. The stones that built it are massive at ground level and diminish as they rise.

From the platform, Riccardo pointed us to a tiny opening. This led to a circular stone stairway that we ducked into and twisted our way down into the main chamber. The Nuragi must have been small, spry people to get in and out. Going in we passed an Irishwoman who wasn’t so small. She leaned against a railing and said with horrified conviction, “There’s no way I’m going to get stuck in there!”

https://www.consumermojo.com/discover-sardinia/

https://www.consumermojo.com/discover-sardinia/

Emerging from the steps as pretzels, we untwisted ourselves and looked around.

We were in a courtyard, once enclosed, next to the main, ground-level chamber.

Riccardo led us in and we stood in the middle of what had once been a complete room dotted by openings in the stacked stone walls. “Can you find the hidden room?” Riccardo asked.

We hunted around until we found a panel on the left wall. That led to an opening. “What was it used for?” Barbara wondered. Riccardo said archeologists can only guess. “Maybe it’s where they kept their spice jars,” Barbara said.

The sophistication didn’t stop with hidden rooms. Many of the building stones, which were volcanic basalt, were shaped into lintels to form window and passage openings.

Light-colored stones mixed with the black volcanic basalt in the tower walls; the Nuragi clearly used whatever was at hand.

Down low, even on a hot day late in June, the air inside the rooms was cool and some of the wall openings were probably used for food storage. A well sunk into the floor provided water.

Four more conical towers, linked by a curtain wall, stood outside the central one and some of these had survived nearly complete for more than three millennia. More towers surrounded these. The tallest of them must have been manned by Nuragic sentries to watch the surrounding countryside for signs of danger.

Outside of these lay clustered dwelling units. Most were round, and would have had roofs built of wood and thatch. Among them were scattered wells and fire pits with openings in the walls for ventilation, stone basins for water, and sites for religious rituals.

It looked like a really rough first draft of a city. Unlike monumental wonders of the distant ancient world like the pyramids or Stonehenge, you could see how the structures served the needs of the people who lived in them, not the glory of their rulers.

It showed that people even millennia ago tended to cluster for mutual advantage, defensively but also socially. You could actually see what the people who built them had in mind. I found it thrilling, and

Barbara interpreted my enthusiasm as a sign that my 0.2 percent Sardinian DNA made me a Nuragi, by affinity if not by blood.

Afterward, Riccardo drove us to the Giara di Gesturi, an upland plateau a few miles north of Barumini.

The road was lined with wild flowers, orange red poppies blazing in the sun.

The road was lined with wild flowers, orange red poppies blazing in the sun.

Riccardo said wild horses lived on the plateau. He wanted to see if they were still around, drinking from two rainwater lakes that usually go dry in summer. “If we see them, be still and not too loud,” he said. “They run away from people.”

We walked for a quarter of a mile along a dusty road until we came to a lake on our left.

It was low but still wet, and there on the back side were about a dozen horses, drinking as they stood up to their ankles in the water. They looked small, and they were all black or lustrous dark brown, a color horse people call bay. Some say they have been here since Nuragic times, others believe they were imported by Phoenicians. Whatever their origins, they’re the last wild horses left in Europe.

“Another,” he said and motioned us to walk farther up the road. After about five minutes, we spotted the second lake, with more horses drinking and nipping at leaves protruding from the water.

Back in the car, we headed to the Casa Zapata, a 16th century Spanish palace that was built over another Nuragic site. Nobody knew this until 1990, when the Barumini municipality was restoring it as a museum.

The restoration took an abrupt turn and now, in addition to displaying Zapata family and church artifacts,

the museum shows through plexiglass panels remains of a Nuragic complex built along the same lines as its Su Nuraxi neighbor.

Back in Cagliari, Riccardo dropped us in the Marina District. He’d given us a wealth of information for his 150 euro fee and we had a great time. Now we were halfway through the afternoon, and we returned to Su Cumbidu for another late antipasti.

We had one more must-see in Cagliari. We walked uphill, and around another hill, and another hill after that until we found the ruins of the Roman amphitheater near the edge of Il Castello. Carved into a hillside in the 2nd century A.D., it sat as many as 10,000 spectators — the entire population of Cagliari at the time — for gladiatorial blood sports. Two tired workers were selling entry tickets in the late afternoon heat, but we found the view from the tree-lined road outside just as satisfying.

Our second night in Cagliari confirmed the first: Italians wherever they are take their food seriously, and if they’re on an island or near a coast that means seafood tops the menu.

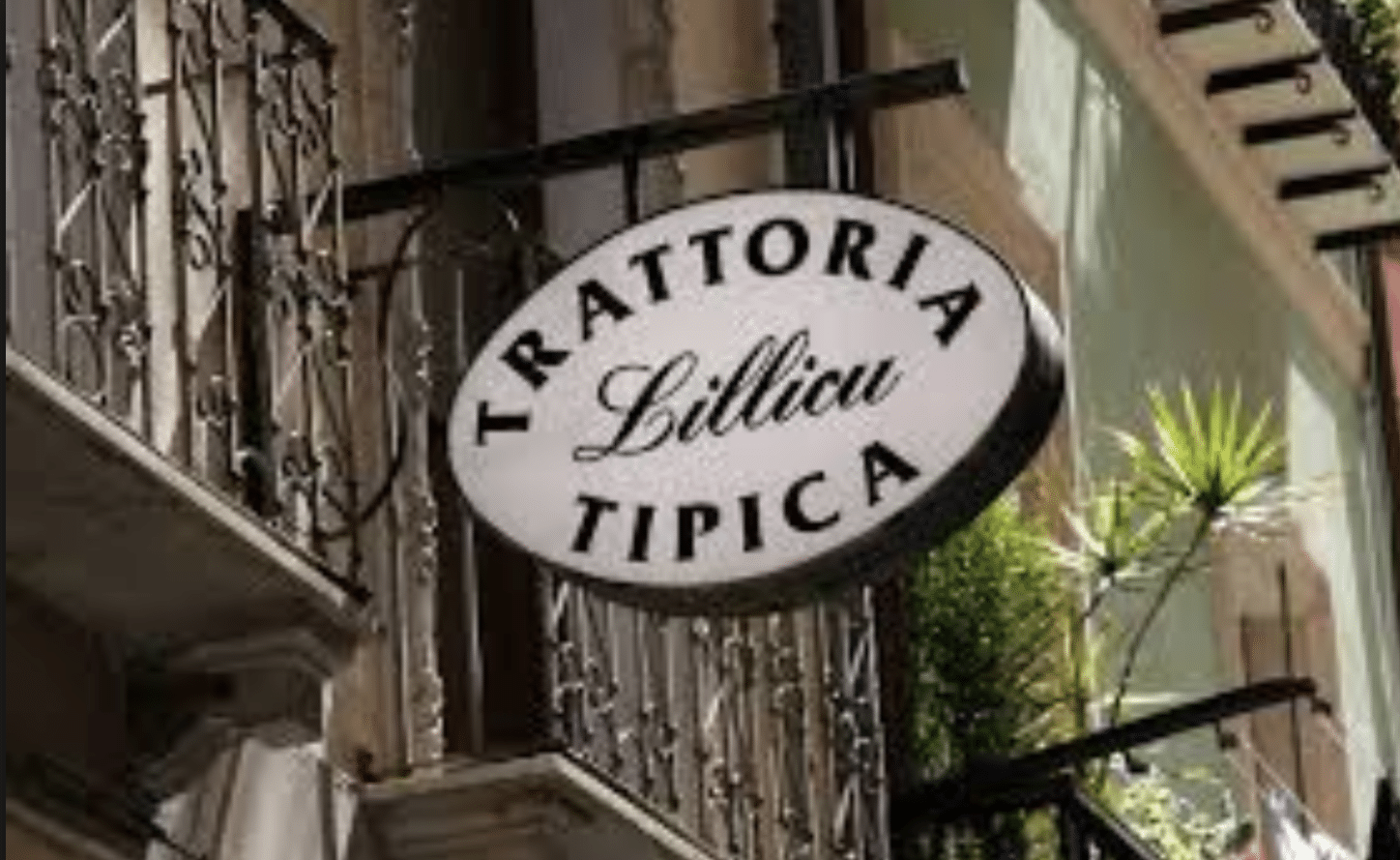

Riccardo enthusiastically recommended Trattoria Lillicu, a family-run place that dates to 1938 and was just steps away from Palazzo Dessy on Via Sardegna. The waiters didn’t hand us menus, they just told us what they had. That included tuna tartare and octopus salad for starters, pasta with clams and bottarga (tuna eggs), and fresh fish prepared how we liked it. With an excellent Sardinian Vermentino, a wine the island excels in, we made our last discovery on a day full of them. This time it was a recipe for happiness.

Read more about Cagliari.