He went back to the Internet and couldn’t find PAS. “The company website disappeared. I finally located a phone number and talked to someone. The man said I have to pay off $24,300, the full amount of the five-year contract. But I didn’t see anything in the contract that says there’s a prepayment penalty.”

The contract Darren shared with us lays out the details. Although he insisted it wasn’t clear to him and wasn’t explained, he said he believed the company representative who negotiated the deal. “I take a person at his word. He told me about the contract and I thought it was okay,” Darren sighed.

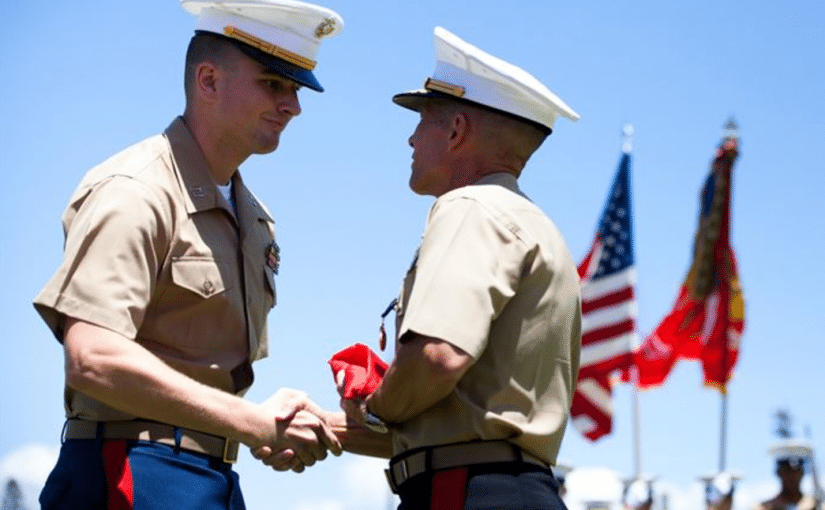

Broward County, Florida attorney Scott Silver told us he represents dozens of former military members who’ve had similar experiences with pension advance companies. “Clients come to me desperate to repay these loans without paying usurious interest rates and they find themselves trapped and unable to to make the monthly payments.”

In Darren’s case, the word “loan” doesn’t appear in the contract. The language describes him as a “seller,” and that apparently is a device commonly used in this industry.

“Seller is a cosmetic way to avoid the truth-in-lending laws,” AARP attorney Jay Sushelsky says. “By not calling the person a “borrower,” it’s not a loan. It’s an advance purchase or sale. So it takes the transaction out of a whole regime of state and federal lending laws.”

Federal and state officials have begun to take notice. Vermont is the first state in the nation to pass legislation that defines these pension advance deals as loans and requires lenders to apply for a license with the state.