Zagreb, Croatia and the Road to Sarajevo

by Nick Taylor

Zagreb was a stop on the famed Orient Express traveling between Paris and Istanbul. Our train was a far cry from the Orient Express, but we had booked into the hotel where its elegant passengers had stopped to spend a night. The Hotel Esplanade, we read, was a stone’s throw from the station and allowed those swanky types to take a breather from the rails.

But I expect porters ferried their bags to the hotel. We, on the other hand, wheeled ours the distance on the sidewalk and then searched for the not-so-obvious entrance.

Once we found it, we entered its Belle Epoque lobby of ivory and black marble and dark wood with the kind of sitting areas that you find in elegant living rooms. Clocks over the doors told the time in seven major cities.

And the hotel guests chatting and milling about seemed to represent them all.

The diversity added to the appeal that since 1925 had drawn travelers and members of the Zagreb social scene. The vibe must have been much different under the Nazis and the Croatian Ustashi who took it over during World War II. But, at the moment, it seemed benign and firmly apolitical.

Our first evening in Zagreb began in the hotel’s 1925 Bar and Cocktail Lounge.

A chandelier of dripping lights the size of a wagon wheel hung over the bar. We thought of spies and glamour and sunk into the deep chairs. A woman in a black dress at the next table smoked a cigarette and nursed a drink in a tall glass. You wanted to order a martini at a place like this but we opted for prosecco.

After drinks we walked to a traditional restaurant called Stari Fijaker, or Old Coach. It was near the upper end of Lower Town, the flat part of Zagreb below the higher, hilly part, called Upper Town. Graffiti marked the darkened masonry of most buildings we passed along the way and we talked about how tired and worn out Zagreb felt and looked. And then the gloom lifted.

We began to pass sidewalk cafes that we would see day and night throughout the city. People laughed and chatted over coffee and wine and browsed through smartphones like they would in any cosmopolitan place.

At the restaurant, our balding waiter made recommendations that came from long experience. His playful near-smile said, “This is what’s best. If you order something else, it’s not my fault.”

I took his advice and ordered the goulash, or what the menu called shepherd’s stew containing beef, pork, veal and venison.

Barbara, independent as always, resisted. She would have wiener schnitzel with polenta, thank you, and not the suggested sausage.

We had bean and cucumber salads on the side and some local wine. The waiter gave Barbara a refrigerator magnet with the restaurant’s logo as a departing gift.

We took breakfast in the Esplanade’s lavish Zinfandel restaurant dining room the next morning while we mapped out our day. One order of business was visiting a cash machine. The Balkans’ currencies are balkanized; Slovenia used the euro but Croatia proudly uses its kuna.

A kuna is worth about sixteen cents, and Croatian patriots and poets adorn the banknotes.

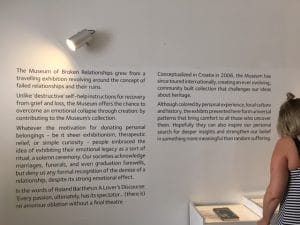

My must-see for the day was the Museum of Broken Relationships, opened in 2006 by a couple who, after breaking up, thought why not display the items each of them had left behind and tell their stories. Barbara wanted to see the Zagreb market on the way to the Upper Town.

We walked along a street bordered by a series of parks and the shade was a relief. A heat wave enveloped the Balkans and the temperature was climbing to near 90 F. The people in the parks didn’t seem to mind the heat. Technicians were stringing cable and setting up for a concert in one park that we passed.

In another, creative souls had produced a beach-like setting complete with lounge chairs and book store.

Broad steps leading to the Upper Town took us to the Dolac market.

Sellers offered local produce and every kind of nut and spice, as well as fruits and vegetables that may have started life elsewhere.

Sellers offered local produce and every kind of nut and spice, as well as fruits and vegetables that may have started life elsewhere.

Local flower sellers in one section peddled fresh and dried bouquets.

In another area we found cheese and fishmongers.

For a minute we fantasized about the fun we could have shopping and cooking here. But for only a minute. We drifted from the market up some steps and across a street to the Zagreb cathedral.

Beautiful, yes. But it also reminded us of the part religion plays in the Balkans. Although the people of this region come from the same South Slavic stock, their ancestors migrated from the Caucuses in the 9th century. Catholics of Croatia and the Eastern Orthodox Christians of Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria have for centuries fought each other and the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania.

The Croatian Catholic Church played an ugly role during World War II when its Archbishop Aloysius Stepinac aligned with the Nazis and the ruling Ustashi. The ultra-nationalist Ustashi came to power in 1929 and killed and terrorized until 1945. During their reign, they murdered hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews, Muslims and Roma in their drive to create a racially pure Catholic Croatia.

After World War II Marshal Josip Tito, who united Yugoslavia as a communist state, and pictured here with Winston Churchill, had Stepinac arrested. He was sentenced to sixteen years in prison. But in 2016 a Zagreb court overturned the conviction, ruling that he did not get a fair trial under Tito.

Now, the twin spires of the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary tower over the capital square and make it the tallest building in Croatia. And Croatians honor Stepinac with a museum next to the church. Croatian Catholics have lobbied for Stepinac to become a saint. But Pope Francis stopped the canonization process and called for a review.

A group of young men wearing traditional costumes took pictures of one another outside of the church and we silently wondered what nationalism meant to them.

We headed into the cool interior, partially to escape the heat. We noticed that the stained glass windows along the sides of the cathedral didn’t tell the usual Bible stories featuring portraits of the saints. They showed instead the kinds of geometric floral patterns more often seen in mosques. But the altar and surroundings were rich with Christian iconography.

We eagerly put religion behind us and began walking toward the Museum of Broken Relationships.

At an open-air cafe in a pedestrian plaza below the market, we stopped to buy water. A burly man, larger even than the normally large Croatian men, heard us speaking English and asked, “Where are you from?”

Turns out Josef – “call me Jossi” – a Croatian Jew, had lived on Roosevelt Island in New York City while he did some work for the Croatian delegation to the U.N. He hinted that his work involved mystery, or spycraft.

He pulled out his phone and showed us pictures of his grandchildren at a beautiful home he owned on the Adriatic coast.

When he learned that we planned to drive to Bosnia, he discouraged us. “Go to the Croatian coast first,” he said, and began mapping out a route we had no intention of taking. But his good humor and enthusiasm made us laugh.

We left Jossi and walked uphill, around a corner, through a stone gate

and uphill some more to a square that opened up around a church with a bright tile roof. This was St. Mark’s Church.

The original dates to the twelfth century and stands as a Serbian Orthodox outlier in Catholic Croatia. Zagreb’s coat of arms, a white castle on red background, took up half the roof. The other half displayed a coat of arms dating to the 19th century, when three Croatian kingdoms under one king were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

We found the Museum of Broken relationships a few blocks away. This little place told stories of broken hearts and missed moments. It felt more human than any museum we have visited. You didn’t find ancient glories, grand sculpture, Greek or Roman columns, or mummies adorned for their voyage through eternity. But you did see small mementoes and read the poignant recollections that accompanied them.

The display featured a modem from an old computer,

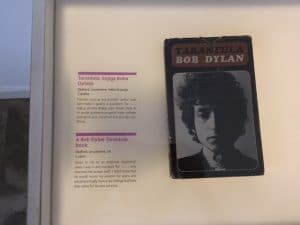

a dog-eared copy of an old Bob Dylan book,

sock puppets, dolls, a plastic flower, all things couples had shared and meant something when they were together.

Donors told stories mostly about love affairs that cooled, but some wrote of departed parents, or of children who died. Some wrote with anger, some with bitterness, some with resignation, but every story brought a pang of recognition. We left the museum with sad smiles at seeing the kind of touchstones that make us all human and realizing that we had been there, too.

We moved from the museum’s soulful stories to the pleasure of a ride on a funicular.

Upper Town stands higher than Lower Town by about 100 fairly abrupt feet, and the funicular, built in 1893, provides a way to quickly get from one to the other. It calls itself the world’s oldest, shortest, steepest and safest funicular. And maybe, at four kunas for a ticket, it’s the cheapest. We entered and fanned our faces with our hats until the car descended its 217-foot track to the bottom.

We dipped into modern Zagreb and a young, hip place called Duck for lunch.

We sat at the counter and ate mussels and a chicken Caesar salad and of course drank Croatian white wine.

At Barbara’s insistence, I discovered the pleasure of shopping at Zara, the Spanish retail chain that offers knock-offs of designer clothes at a fraction of the price. The extreme heat forced me to get a few new shirts.

Barbara found a hair salon across from the hotel that featured her favorite Aveda products and enjoyed talking to the excellent hairdresser, Luciana Sakic.

When the young woman learned that we planned to head to Bosnia, she shook her head. “My father was there during the war in the ’90s. But when I ask him to talk about it he says, ‘Please Luciana, you don’t want to know. Don’t make me talk.'”

That evening, we ate at the Esplanade’s less formal Bistro restaurant. The dated sound track played an incongruous loop of Frank Sinatra classics. Our young waiter said, “I’m going to get some new music. They said that I could update it. Are you coming back this way? You’ll hear it.”

Barbara ordered the house special risotto and I had asparagus. We ordered a bottle of Croatian pinot noir to accompany my veal cheek main course

and Barbara’s smoked pork dish.

The next morning, we had breakfast in the dining room and watched as a family of six Chinese women in their twenties fawned over their elderly patriarch. They patted crumbs off his shirt and belly and passed him the watches and other goodies that they pulled from their shopping bags. This family, we later learned, had traveled with a larger group from China making a European tour.

Time to leave, and we headed to Hertz’s downtown office through forests of graffiti-painted apartment buildings. “Look at it!” the driver cried, waving a hand. “Six meters, nine meters high, everywhere! This government doesn’t care. They don’t know how to do anything right.” He said he longed for the days of Marshal Tito, when order ruled.

When he learned we were driving into Bosnia and Herzegovina, he told us to obey the speed limits. “If it’s fifteen, don’t go sixteen, go fourteen,” he said. “And take a few euros in case the police pull you over. They do it old style there. Not like here in Croatia.”

Soon we drove southeast in a brand-new red Suzuki Swift with a five-speed stick and a gasoline engine, a change from the diesel cars you usually get in European rentals.

We discussed the route as we drove. Barbara wanted to go through Banja Luka, the de facto capital of Serbian Bosnia. I wanted to avoid it.

The Dayton Accords that ended the fighting in the Balkans war designated 49 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina as Serbian areas, or Republika Srpska.

The Serbs under Slobodan Milosevic had wanted the whole thing, laying siege to Sarajevo and shooting civilians in the street from sniper outposts in the hills, and slaughtering Muslim men and boys at Srebrenica. I felt convinced the Serbs still wanted more.

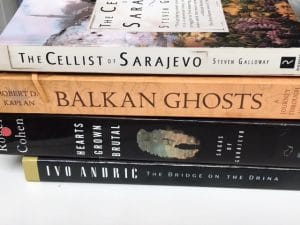

My reading of Robert Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts, Roger Cohen’s Hearts Grown Brutal, Steven Galloway’s novel The Cellist of Sarajevo and Ivo Andric’s The Bridge on the Drina had prepared me for the trip.

Fortunately I had an ally in Google Maps, which told us that my route was faster.

We sped by the exit to Banja Luka and left the highway at Slavonski to cross into Bosnia at Brod.

We joined a long line of cars passing through the Croatian exit point. Pedestrians and bicyclists seem to move easily between the two countries.

At the Bosnian checkpoint border patrol officers flipped through our passports and looked at the car papers and waved us along in the Serbian part of Bosnia.

Republika Srpska, a jagged horseshoe, curves from Bosnia’s northern border with Croatia to its eastern borders with Serbia and Montenegro, except for a dollop at the curve of the horseshoe that is the self-governing district of Brčko.

So we had avoided Banja Luka, but the broad vertical stripes of the red, white and blue Republika Srpska flag still greeted us as we crossed the border.

We followed a two-lane road south through gentle farmlands.

The tightly coiled hay bales we’d seen in the farm fields of Croatia now gave way to looser haystacks piled upright, protruding on the top like upturned breasts.

The road led south through Doboj, where the signs pointing west to Banja Luka finally disappeared and we left mini-Serbia for a while.

We drove into the mineral-rich part of Bosnia-Herzegovina and through Zenica, a factory town that produces aluminum and steel.

Its huge, mud-drab warehouses and factories turned their ugly faces to the highway, but they soon gave way to beautiful small mountain towns dotted with minarets and a few church steeples.

After a six-hour drive, we entered Sarajevo.

![]() Read A Trip to the Balkans Part One

Read A Trip to the Balkans Part One

![]() Read A Trip to the Balkans Part Three

Read A Trip to the Balkans Part Three