by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

We traveled overnight to Copenhagen from Oslo on the DFDS ferry. We passed the tip of Denmark in the night and when we awoke, we saw that Sweden embraced us on on our left and Denmark on our right. The horizons pinched in as we neared Copenhagen.

Entering the harbor we passed a pair of big cruise ships. They reminded us that Denmark’s capital, like all the Scandinavian port cities, has served seafarers at least since the age of the Vikings. Ships out of Copenhagen can reach the Baltic and the North seas with equal ease. Indeed, we later learned that some cruises around the British Isles sail from Copenhagen and these ships were ready to leave.

By ten-thirty we were off our boat and trying to get oriented as we looked out the windows of a taxi. We sped through neighborhoods and a shopping district and remembered that low-lying Copenhagen is a city built on islands both natural and manmade. Historic Christianshavn, a short bridge removed from the shopping district, grew up on artificial islands built in the 17th century.

That’s where we were headed. We were booked at The NH Collection Hotel. Right down the narrow street we had a frontal view of Christian’s Church, built in the 1750s for German worshippers. Now it’s a Church of Denmark parish church.

Naturally, the hotel check-in time was three and the lobby was jammed with others like us, eager to get into rooms that weren’t ready.

We wanted to get in as much of Copenhagen as we could in our 48 hours, and we had a rough idea of what we wanted to see. So we left our bags in a storage room and hit the streets. Our first stop was a nod to our counter-culture lives in the 1960s and early ’70s. Are you guessing what the name of our destination might be? Try Pusher Street.

A sign at an entrance welcomes visitors to Christiania, which is also known as Freetown.

The Pusher Street name came from the neighborhood’s open marijuana trade, but other factors were at work as well. The Danish navy had abandoned some barracks, which were taken over in 1971 by squatters who created a self-governing commune. The residents who gained partial independence in 1989 have operated as a “pseudo-anarchist consensus democracy.”

Photos are frowned on, so we didn’t take many, but the buildings had an improvisational look. We wandered among the graffiti-painted shops and stalls feeling as if we’d been transported back to a rural St. Mark’s Place in the late 1960’s.

Several weeks after we visited there was an apparent gang war on August 26. Hells Angels and a gang called Loyal to the Familia have fought each other here before for dominance of the cannabis trade. In the latest spate of violence a man was killed and five people were wounded. After the shooting the mayor of Copenhagen urged people not to buy marijuana in the community.

The Danish government is considering ways to shut Christiania down. Fewer than a thousand people live here, but it’s a tourist attraction that gets half-a-million visitors a year. Leaving the community, you pass under a sign that announces your return to the EU.

It began to drizzle, but we continued to wander. We passed the Our Savior Church, that dates to 1752 and its tall tower with outside stairs. We were not among the 200,000 annual tourists who climb the 400 steps to the top. But we did admire the architecture.

Leaving Christianshavn, we crossed the canal into central Copenhagen.

We were headed toward the National Museum of Denmark but on the way found ourselves on another island. Or islet, to be accurate. Slotsholmen translates into The Castle Islet and looks on a map like an upside-down fruit cup, sided by canals all around. It’s been the seat of Denmark’s monarchy since the Middle Ages and now its government and courts. The massive Christiansborg Palace looms over its large square.

The parliament convenes there, and it houses the prime minister’s office. If you’ve ever streamed the Danish political drama “Borgen,” which translates into “castle,” you’d recognize the place.

The current monarchy started in 1863. For you royal watchers, that’s the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. King Christian IX was the first of that family to the throne, and there’s a statue of him out front to prove it.

Queen Margarethe II is the latest in that line. She’s been Denmark’s queen since she was crowned in January 1972.

From “the island of power,” as Slotsholmen is also called, we walked under gathering clouds to the National Museum of Denmark. Like the other Nordic countries, Denmark’s Viking era — roughly 300 years starting around 790 AD — profoundly shaped its history. This museum features a handsome display that takes you on a deep dive into Viking history and culture.

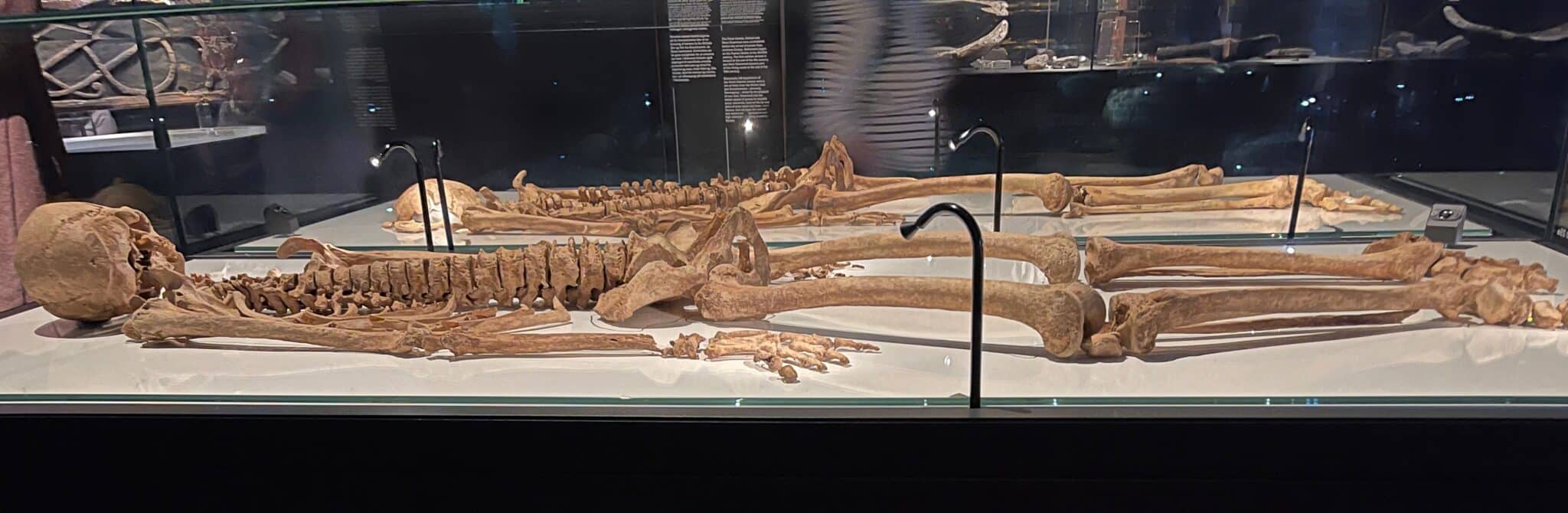

A pair of male skeletons gave us examples of how the Norse people lived and died. One skeleton, a man in his fifties thought to be a farmer, was unearthed in what’s now central Denmark. The other, in his late teens or early twenties, was found with other skeletons in Oxford, England. Remarkably, DNA testing showed them to be related, half-brothers or an uncle and nephew. Markings showed both died violent deaths, a hallmark of the Viking Age of raids and plunder. But it also showed us how tall the Vikings in 800 to 1000 AD were. Both men were just under 6-feet.

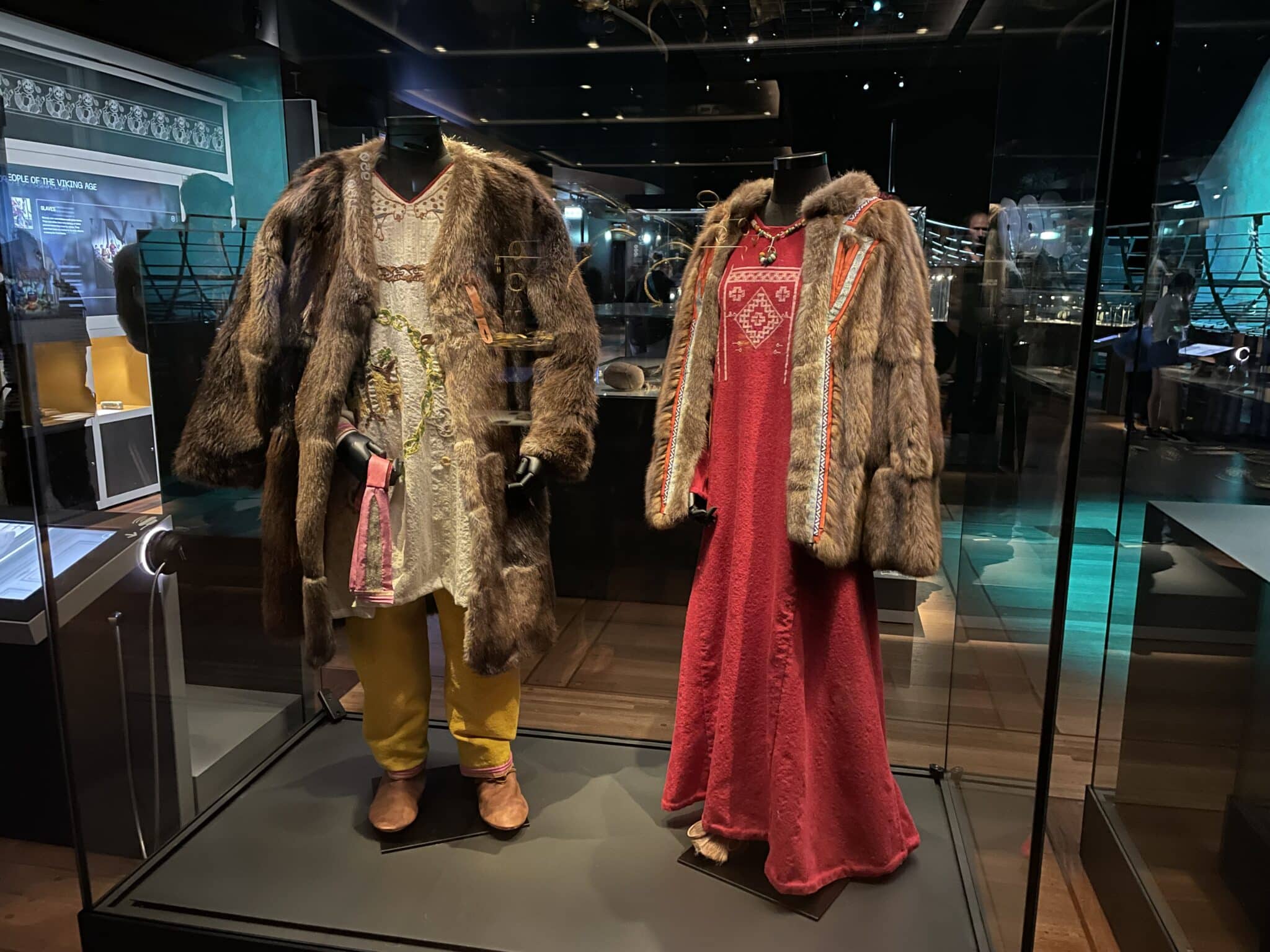

The museum also showed us what Vikings looked like when they were alive. If you envision a blond giant wearing a horned helmet, think again.

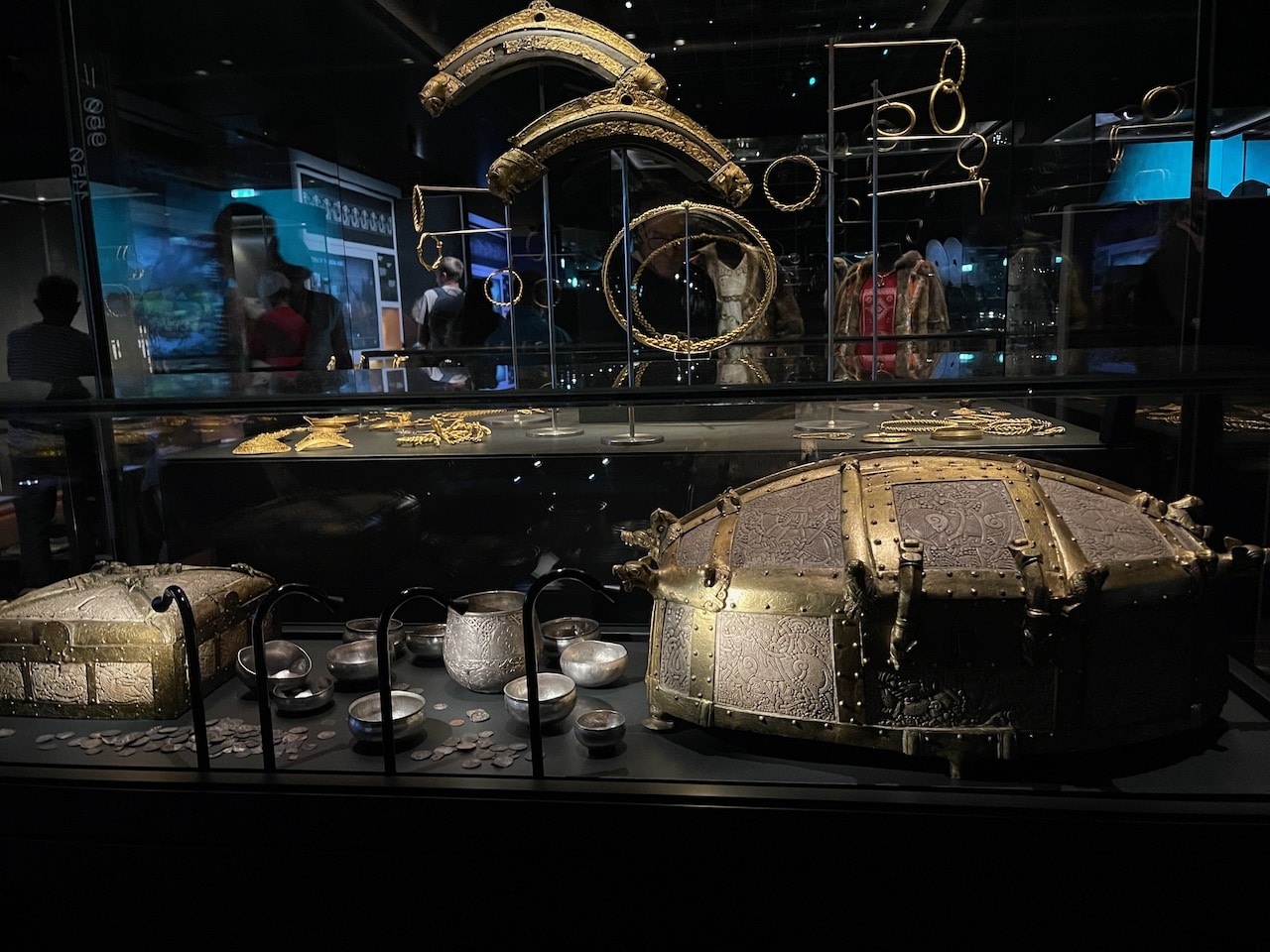

And if you think wealth gaps are something new, think again about that, too. The fellow above was probably a farmer, but another museum exhibit showed the finery that richer men and women wore, their jewelry and heavily embellished weaponry.

A word about the food. Everywhere we went in Scandinavia restaurants talked about “Nordic gastronomy,” and the food was outstanding even in the busy museum restaurant.

Someone swiped our umbrella, which we were asked to leave in a stand. That left us dodging serious rain drops as we ran back to the hotel. Our spacious room overlooking the canal was ready and we dried off and prepared for dinner.

Someone swiped our umbrella, which we were asked to leave in a stand. That left us dodging serious rain drops as we ran back to the hotel. Our spacious room overlooking the canal was ready and we dried off and prepared for dinner.

It was still raining when we cabbed to a lovely small restaurant called Marv and Ben. The innovative kitchen uses local, seasonal food from small producers. Michelin gave the restaurant the Bib Gourmand award, and that means it considers the food innovative and really good for a not-over-the-top price.

The restaurant on two levels of a small house delivered for us. We didn’t take photos of everything because it was a teeny place and we didn’t want to be obnoxious.

In the morning, more rain. From our hotel room window we looked out on the bridge from Christianshavn to the central city and saw what commuting looks like in Copenhagen. Bicyclists in rain slickers, some holding umbrellas as they pedaled, streamed across the bridge into the central city, easily outnumbering the cars.

It turns out that Copenhagen is one of the most bike-friendly cities in the world, and around 60 percent of its commuters bike to work or school. Infrastructure helps; added to streets and sidewalks are a third component, bike lanes, and they’re everywhere. This means tourists have to be alert, but speed limits for cars and bikes add a safety factor. We never got run over, but we had to jump fast once or twice.

After the hotel breakfast we took a taxi to the Museum of Danish Resistance, in Churchill Park near the harbor where our ferry had docked.

The underground museum lays out the story of the resistance using five real-life characters who chose to resist or collaborate with the Germans.

When Germany invaded the country on April 9, 1940, the Danish King and the government made the decision to remain and cooperate with the Germans. The vast majority of people went along with it.

But others formed an active underground resistance that blew up factories and tactical sites and fought the Germans any way they could. The excellent exhibit tells a sobering story.

In 2013 the museum was destroyed by arson, but the photos and artifacts survived and it was rebuilt.

Back at street level, we bought new umbrellas and dipped into a place in the gallery district called Restaurant Salon for lunch, which we later learned is described as old school French. People at a nearby table were enjoying many bottles of wine. But we opted for a simple lunch.

It was excellent but priced for expense accounts. Barbara’s salad niçoise and Nick’s beef tartar (below) with French fries — we drank water — cost $75 worth of Danish crowns.

Danes say taxes are the reason things cost so much.

A waiter at the restaurant recommended that we visit Rosenborg Castle, built as a royal summerhouse in the early 17th Century. It was a royal residence only briefly but now it houses the crown jewels and crown regalia. The King’s Garden, where it’s situated, is now Copenhagen’s most visited public park

We got to the park and people were circling to line up. It was pouring and we were wet and ready to call it a day. After a good walk, we found the subway that took us almost to our hotel.

It was still raining at 8 p.m. when we headed out to dinner. But fortunately the restaurant, No. 2, was down the street on the canal close to the hotel. This was the sister restaurant to a two-starred Michelin restaurant and No. 2 offered beautifully prepared food using local ingredients in the Nordic style that we fell in love with.

Our check, again, spelled out the source of local cost complaints — the 25 percent value added tax applied to restaurant bills.

We walked back to our hotel along the canal ready for the next day and our train trip to Stockholm.

Thank you for sharing your wonderful trip. Places I’m pretty sure I would not get to visit.